Switzerland's farmers become landscape gardeners

- Published

Species like quince have no commercial value but bring money for those cultivating them

UK farmers will no longer receive subsidies after Brexit but instead get payments for "public goods" such as planting meadows and boosting access to the countryside under proposals from Environment Secretary Michael Gove.

No one is quite sure yet exactly how it will work. But one country, non-EU member Switzerland, already offers its farmers direct payments for looking after the landscape, as the BBC's Imogen Foulkes reports.

"We have apple, cherry, and quince," says Fritz Bernhard. "We make juice, and schnapps, but only for ourselves."

His farm, located a few kilometres north of the Swiss capital Berne, is benefitting from a direct payments scheme.

An orchard of fruit trees, all ancient species, brings much needed income for him and his family. But the fruit itself has no commercial value.

Instead Fritz is being paid for biodiversity: these tree species would be extinct in Switzerland if they relied on market forces for their survival.

Milk price plunges

Fruit tree cultivation is one of the most common ways for Swiss farmers to boost their income nowadays.

On the edge of his land, Fritz has also planted traditional chestnuts; these too command a payment.

The European Union currently spends about €59bn (£51bn; $72bn) every year supporting its farmers.

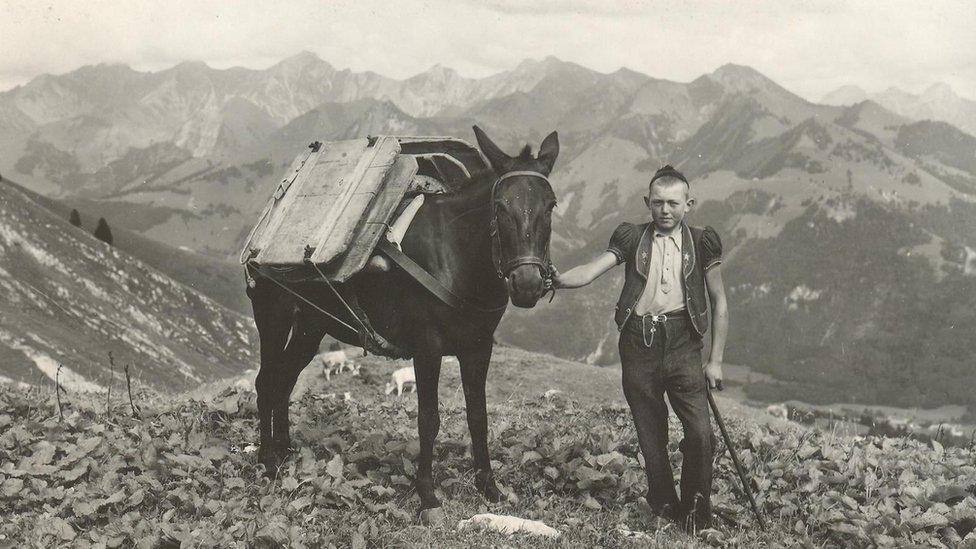

The scheme is seen as crucial for the survival of rural communities like those in the high Alps

Swiss farmers, especially the dairy farmers, are as proud as any others of their ability to produce food. Without them, Switzerland would have starved during World War Two.

Post-1945, the Swiss government rewarded its farmers by setting a very generous milk price, and by guaranteeing to buy every kilo of Emmentaler and Gruyère cheese produced.

Globalisation forced an end to those policies. In the last 30 years, the price per litre for Swiss milk has dropped by half.

Switzerland's farmers, most of whom work small, geographically difficult plots of land, have felt the chill wind of the global market, and realised they cannot compete.

"Costs in Switzerland are very high," explains Beat Röösli of the Swiss Farmers' Union.

Nevertheless he points out, no country wants to produce no food at all. "If we want to produce at least a part of the public consumption it's necessary to have public support of some kind."

Fritz Bernhard's beef is sold to local butchers but he is still being paid for his fruit tree cultivation

Under the Swiss scheme, farmers receive payments for looking after the land.

"If we maintain a beautiful landscape, we can also request a salary, a certain remuneration for that," explains Mr Röösli.

Tourists, he adds, expect to see a cultivated countryside in Switzerland. "If they want to see wilderness they go to Canada, they go to Russia."

'Paid to create a façade'

Protecting the environment on a day-to-day basis is another key pillar of Switzerland's direct payments system.

Fritz Bernhard's farm is next to a nature reserve, so an additional income generation for him is to look after it, and to keep its public paths clear.

The traditional image of Switzerland is of neat farmland and alpine views

But he does still produce food: not milk like his forebears, but beef, which he sells directly to local butchers, and barley and malt for a local brewery. "We have a mixed farm, very typical in Switzerland now," he says.

Fritz and his wife Monika derive 70% of their income from food production, and 30% from direct payments.

This puts them at the more successful end of the Swiss food production business. But both are worried Switzerland may be getting the balance wrong.

Monika has even wondered whether she will end up being paid to put geraniums on her windowsill.

"Sometimes I feel we're being paid to create a façade," she says. "It's not motivating. I'd like the food we produce to be valued more."

Generous system for a wealthy country

Switzerland's consumers spend around 6% of their income on food. That is less than their European neighbours, even though their salaries are significantly higher. But other costs make huge inroads into the Swiss pay check - health insurance in particular.

However much Swiss farmers might want their neighbours to pay more for food, the government seems to have concluded that is not likely. But the direct payments system, now costing over $3bn a year, does have the support of the majority of voters, because of its emphasis on "public goods".

The Bernhard family derive 30% of their income from direct payments

It is, says Mr Röösli, crucial for the survival of rural communities, especially those in the high Alps.

"Without it [direct payments] most of the farms today would stop farming, especially those in the mountains" he says. "Today many of the farmers' turnover is 75% direct payments, and only 25% selling products. There is no survival only selling products."

With the system, Switzerland now produces over half of all the food it eats. But in comparison with what the EU pays in agricultural subsidies, Swiss direct payments actually cost more.

The UK's 200,000-plus farms receive just $3.4bn in subsides. Switzerland's 50,000 farms get over €2.3bn in direct payments.

The Swiss scheme has environmental protection as one of its key elements

So could the Swiss system be a blueprint for UK farmers post-Brexit? Mr Röösli is not sure.

"In Switzerland we're many people in a small country, we have good jobs, we have high salaries" he points out. "So you see people have money to invest in nice things like landscape. I'm not sure if in Great Britain people are so willing to spend their taxes for these public goods."

- Published4 January 2018

- Published5 January 2017

- Published28 October 2017

- Published19 June 2023