EU shadow-boxing towards Brexit

- Published

France and Germany are the big powers that Theresa May (R) has to convince

The world and her mother, brother, sister and aunts are more than aware by now of the splits in the British government over the kind of relationship the UK should have with Brussels after Brexit. But how united is the EU?

We keep hearing in social and traditional UK media about supposed EU plots, plans and intentions for Brexit. But are all 27 EU countries, plus the European Commission and Parliament, really singing from one hymn sheet?

If they were, it would be an absolute first.

The EU is famous for its internal bickering: small countries resenting larger ones; larger ones trying to dictate; splits between northern and southern Europe, never mind east and west.

As a result, EU countries find it hard to reach consensus over most things - migration, ever closer union, foreign policy. So why should it be any different over Brexit?

Chinks in EU armour

In fact, the wisdom across the Channel is that if only Theresa May and her government had had their Brexit ducks in a row from the moment they triggered formal negotiations with Brussels, they would undoubtedly have had the upper hand. One tight, crack team against an overgrown, unwieldy, fractious bunch.

But quite the reverse happened in stage one of Brexit negotiations last year.

The UK side appeared to the Europeans as shambolic, divided and (initially) ill-prepared, while the EU put on a rare show of unity - largely helped by the fact that all EU players were shoulder-to-shoulder in pressurising the UK to honour financial pledges made while still a member.

But fissures in the EU armour are now showing as we approach Brexit negotiations on the future EU-UK relationship.

Working groups from the 27 EU countries meet regularly in Brussels to discuss different aspects of Brexit.

They say they're finding it tough to agree a common position on future relations with the UK, as long as the British government remains opaque over its stance.

It is proving a hard grind for Brexit negotiators David Davis (L) and Michel Barnier

Listening to grumbling European players, it would be tempting to paint them as divided too, between the camps of dogmatists and pragmatists: those who value trade, security and other relations with the UK over an EU rule or regulation; and others who believe the integrity of the EU rulebook governing, amongst other things, the European single market, is ultimately the higher prize.

An influential player from a smaller EU country told me: "We all hate that the UK is leaving, but this will always be an important relationship. One contract binding us to the UK will simply be replaced by another. We have to be practical. And positive."

EU big guns France and Germany are proving to be the most hardline. "Paris above all," one EU diplomat told me. "Is this payback for Waterloo? I don't know, but sometimes the rest of us can only roll our eyes."

Now, tempting as it may be to hear comments like that and think 'Aha! The EU really is out to punish the UK for leaving', my sense from meetings with key figures is that the overall mood is one of growing pragmatism and gradual detachment.

Read more on Brexit:

In the UK Brexit continues to hoover up the nation's headlines and political energy - despite government attempts to focus on other issues of public concern like health and education.

But in the rest of Europe, there is not so much focus on Brexit.

On Friday the leaders of the 27 EU countries meet to debate life after Brexit (primarily how to plug the hole in the EU budget that the UK will leave behind), rather than discussing what to do about the UK.

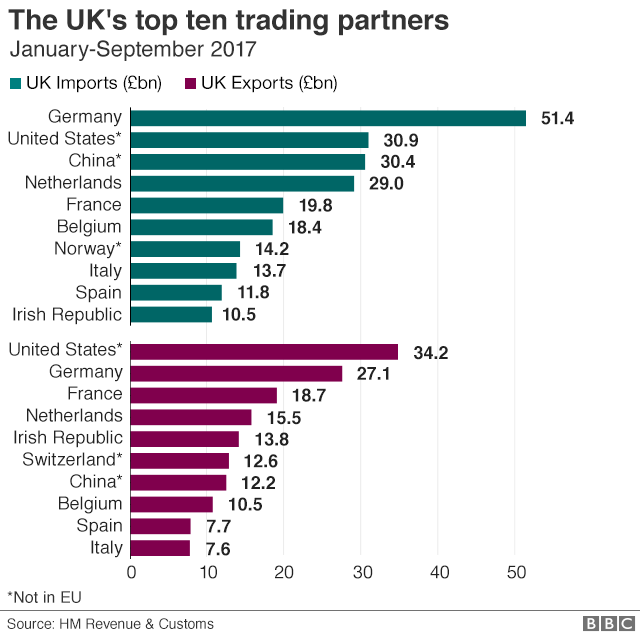

Of course the Danes worry about fishing, the Germans about cars, the French about the impact of Brexit on the port of Calais. But for most EU countries, trade with the UK is not the be-all and end-all.

No 'cherry-picking'

You can expect the EU's chief Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier to maintain a hardline stance in Brexit talks for now.

The EU has long dismissed the UK aim of "cherry-picking" sector-by-sector privileged access to the single market.

EU diplomats like to refer to the UK government's "three basket" idea of varying alignment/divergence in regulations as "fit for the waste paper basket".

But remember we haven't yet actually started formal negotiations on EU-UK future relations.

They won't begin until around Easter at the earliest.

Blueprint, not final deal

In the meantime there's a lot of shadow-boxing going on.

These will be no ordinary trade negotiations between two parties, after all.

Brexit is a political event for the UK and EU.

Both sides will want to demonstrate to their constituents that they hammered out the best possible deal in their interests.

But it's also important to bear in mind that what we are working our way towards here in the Brexit process - ie before the UK leaves in March 2019 - is in EU-speak "a political understanding on the future relationship between the EU and the UK".

Not a final trade deal.

EU law dictates that a member has to leave the bloc and become an outsider or, in EU-speak again, a "third country" before it can hammer out new trade and other relations with the EU again.

So although now feels like crunch time, with speculation of a showdown between in-fighting members of the UK cabinet, and intra-EU differences on Brexit also coming to the fore, arguably in good old Brussels tradition there is a huge opening to kick the can down the road.

That is why EU diplomats are quietly confident now that - from their side at least - a Brexit deal can be struck by March 2019.

Reaching only an "understanding" on the shape of future relations will allow both the UK and the EU more time during the planned (but not yet agreed) transition period after Brexit to hammer out the details on trade, services and more and - maybe - reach a compromise on both sides.

The potential is there, though predictions carry a strong health warning.

- Published16 November 2017