The Spanish rappers getting 'terror' sentences for songs

- Published

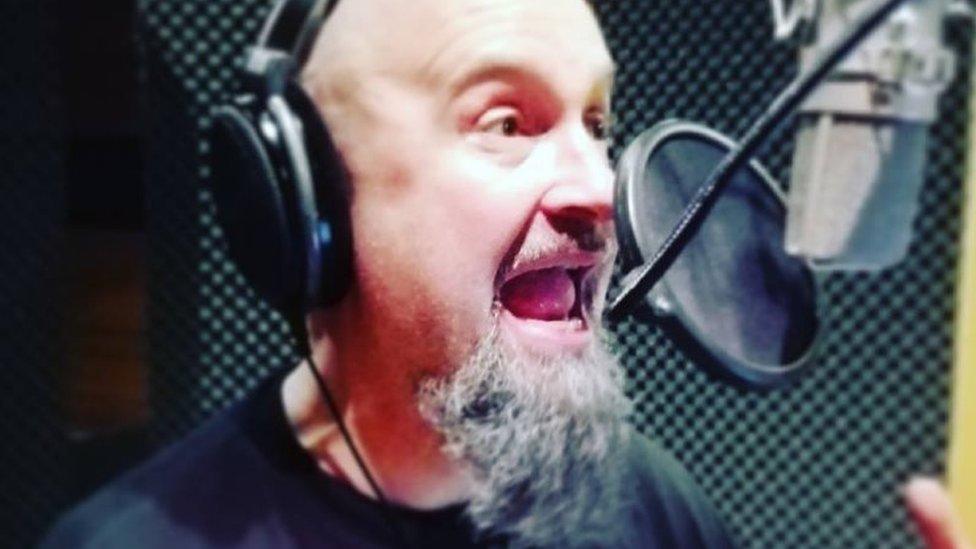

Strawberry says Spain's measures have affected freedom of speech

César Strawberry has found it hard to concentrate on his music recently.

The singer found fame in Spain with rap-rock band Def Con Dos and their notoriously explicit lyrics.

But his controversial commentary has also brought him into direct conflict with the Spanish state.

"It's a co-ordinated strategy aimed at making people scared of speaking out, of expressing themselves and at cutting back a system of freedoms," says Strawberry.

"Sadly, in Spain the government of Mariano Rajoy has embarked on a path which seeks to copy Turkey, rather than France, Germany, Britain or Sweden."

In 2017, Strawberry received a one-year jail sentence for glorifying terrorism and humiliating terrorism victims in what he claims were some humorous Twitter posts - one suggested giving the king a "cake-bomb" for his birthday.

Allow Instagram content?

This article contains content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Instagram cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The 54-year-old has not gone to jail because in Spain sentences of less than two years without a prior conviction are usually suspended.

But he believes his country's government and justice system have embarked on a campaign to slash basic rights of freedom of speech - and that musicians like him are among the main targets.

'You can't limit art'

Since his conviction, there has been a litany of other cases in which performers, and rappers in particular, have faced similar legal action in Spain over their content:

In December, 12 members of the rap group Insurgencia each received two-year jail terms, for glorifying terrorism in one of their songs

In February, the Supreme Court confirmed a three-and-a-half year jail term for Mallorcan rapper Valtònyc for glorifying terrorism and insulting the monarchy in his lyrics

Earlier this month, Catalan rapper Pablo Hasél also received a two-year sentence and a fine of 37,800 euros (£33,500; $46,700) on similar charges

The rash of cases spawned the hashtag #RapearNoEsDelito ('rapping isn't a crime') on Twitter and sparked a debate about the limits of freedom of speech in Spain.

Valtònyc has been jailed for insulting the monarchy and glorifying terrorism in his material

"The countries of the world can be divided into two," says the editor of El Diario newspaper, Ignacio Escolar.

"Those where slander and insult are punished with a fine or with compensation for those affected; and those where what you write or say can land you in prison."

Read more about Spain

Strawberry, Escolar and others believe the courts are deliberately targeting leftist, anti-establishment artists who are deemed a threat to conservative Spain.

"You can't limit art," Valtònyc says. "If these limits had been applied to Picasso's Guernica, we wouldn't have the art we have now."

Earlier this week, human rights group Amnesty International reprimanded Spain, external for what it called "a sustained attack on freedom of speech", saying its law against glorification of terrorism was "draconian".

But the government disagrees. "We have to fight against any sign of extremism or intolerance," Interior Minister Juan Ignacio Zoido says.

Valtònyc rapped in one song: "I want to send a message of hope to Spaniards: Eta is a great nation," in a reference to a speech by ex-Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, who had praised the Basque militant group in a slip of the tongue.

Spain's Professional Association of Magistrates (APM) defended the sentence against him, arguing that "freedom of speech is not an absolute or unlimited right".

Raised the pressure

In 2011, the Spanish High Court investigated five cases of alleged glorification of terrorism; in 2016 it probed 38 cases.

The increase in sentences comes amid the challenge of combating radicalisation and Islamic extremism in Europe.

Political turmoil over the recent drive for independence in Catalonia has also heightened tensions and prompted allegations of political interference in the justice system.

Pablo Hasél was convicted of praising terroris in his tweets

But many of the recent sentences are linked to mentions of Eta, which killed over 800 people during a four-decade bloody campaign.

Although Eta has not killed since 2010, the judiciary has raised the pressure on those suspected of sympathising with or joking about the group.

Joaquim Bosch, a magistrate and local spokesman for the association Judges for Democracy, says he is worried about the recent increase in cases, but that comparisons with countries like Turkey are exaggerated.

Bosch attributes the Spanish clampdown, in part, to the justice system's confusion at how to deal with social media.

He also points to new, tougher, anti-terror and public order laws, many of which are open to the interpretation of judges.

"There's a worry in some sections of the judiciary that in a short period of time there could be hundreds of people given jail sentences in Spain for songs and for jokes and comments on social media," Mr Bosch said.

Rappers are not the only ones to have already fallen foul of the law.

In 2016, two puppeteers, Alfonso Lázaro and Raúl García, were arrested in Madrid after staging a children's show in which one of their puppets held up a placard that read: "Long live Al Qaeda-ETA."

The two men spent five days in prison before their case was eventually shelved.

The artwork Political Prisoners was removed from Madrid's annual art fair in February

Religious sensibilities have also been drawn into the debate. In one bizarre case, a 24-year-old man in the southern city of Jaén was fined 500 euros (£440; $615) for posting on social media a superimposed picture of his face on the body of a wooden sculpture of Jesus.

Some warn that the supposed hard line being taken by the courts is prompting self-censorship.

In Madrid, the operator of the venue staging the city's annual art fair withdrew a work in February because it was titled Political Prisoners and included pixelated photos of four jailed Catalan pro-independence leaders.

César Strawberry fears future generations of artists and musicians will be afraid to express themselves freely.

"If all this goes on much longer there's going to be a generation of Spaniards who censor themselves."

- Published30 March 2017

- Published22 January 2015

- Published21 August 2023

- Published18 October 2019