Europe migrants: Austria to seize migrants' phones in asylum clampdown

- Published

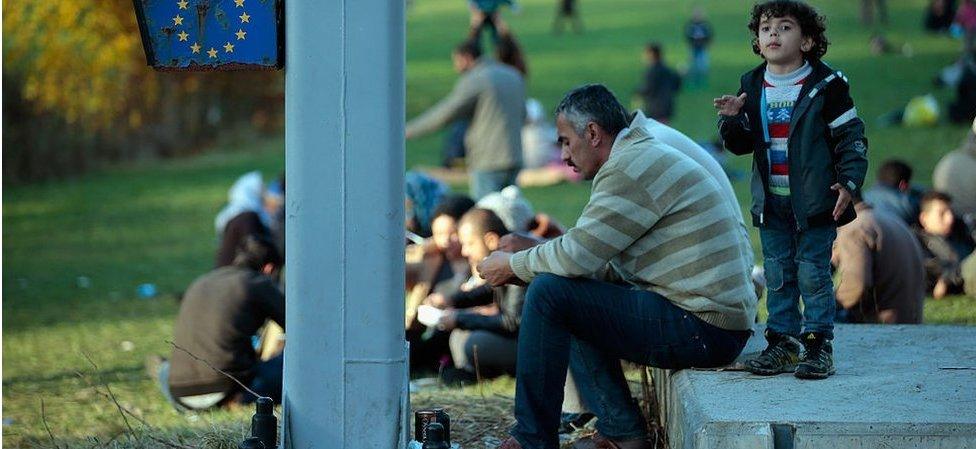

Austria plans to allow authorities to seize cash as well as mobile phones from asylum seekers

Austria's government surged to power late last year with a promise to stop illegal migration and crack down on refugees, and its latest move is to target their phones.

Asylum seekers will be forced to hand over their mobiles so the authorities can check their identities and where they have come from, the cabinet has agreed.

If an applicant is found to have previously entered another EU country where the "Dublin regulation" is in force, they could be sent back there. Under the Dublin rule, people typically have to seek asylum in the first EU state they reach.

In 2015, at the height of Europe's migrant crisis, over 90,000 people applied for asylum in Austria, more than 1% of the country's population.

Initially the refugees were welcomed, but the mood in the country quickly changed.

Support for the far-right, anti-immigrant Freedom Party - then in opposition - grew, and Austria's centre-right conservative People's Party, led by Chancellor Sebastian Kurz also campaigned strongly against migration.

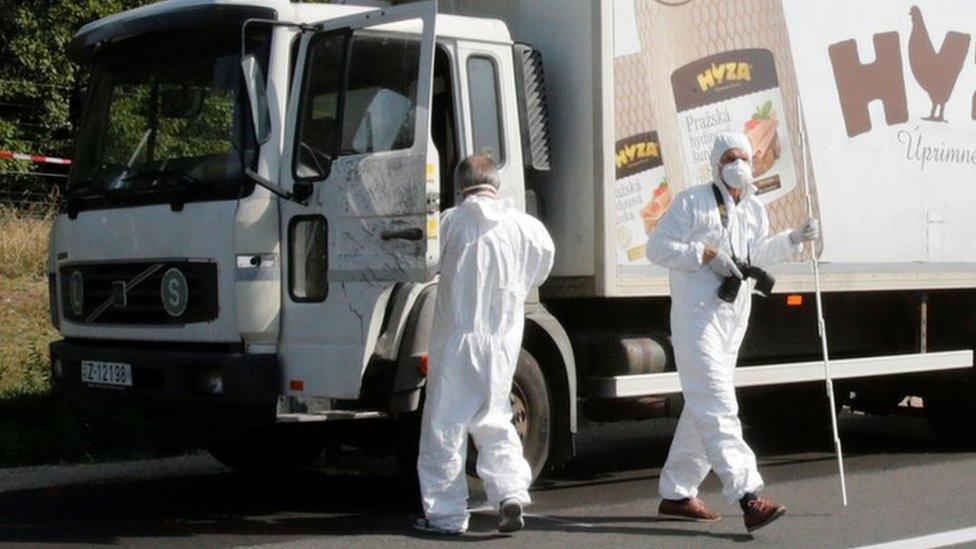

These days, since measures were introduced to try to close off the Balkan route, the number of migrants reaching Austria has dropped significantly.

In the first three months of this year, 3,992 people claimed asylum in Austria, compared with 14,400 in the same period in 2016.

But the government is continuing with its hard line.

It wants to end what Interior Minister Herbert Kickl, of the Freedom Party, calls "abuse" of the asylum system.

Sebastian Kurz, from the centre-right conservative People's Party, campaigned against migration

The bill does not just target mobile phones. It will also allow the authorities to seize up to €840 ($1,037; £730) in cash. The money will be used to pay for the upkeep of migrants as they wait for their asylum claims to be processed.

Austria is not alone. Denmark, Germany and Switzerland have also permitted the confiscation of valuables belonging to refugees to pay for their stay. In Denmark, some reports suggest the authorities have not received large amounts of money from the policy.

"We have very deliberately set ourselves the goal of fighting against illegal migration but also against the misuse of asylum," Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz said at a news conference after the weekly cabinet meeting.

'Disproportionate interference'

The bill, which must now be passed by parliament, would also force hospitals to tell the government when asylum seekers will be discharged, to ensure effective deportations.

And the measures mean that refugees will only be able to apply for Austrian citizenship after 10 years, as opposed to six years which is currently the case.

Human rights groups have criticised the Austrian government's plans (file photo)

Deportations of asylum applicants convicted of crimes will also be speeded up.

Opposition parties and human rights groups have condemned the plans.

Amnesty International said the plans to seize phones was "a completely disproportionate interference in people's private affairs", and that displaced people were being lumped together as cheats or a security risk.

It said the only thing the bill achieved was to create more "uncertainty and mistrust among the population".

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

- Published13 March 2018

- Published16 December 2017

- Published14 December 2017

- Published21 June 2017

- Published27 April 2016

- Published14 April 2023