Why Armenia 'Velvet Revolution' won without a bullet fired

- Published

Protesters objected to Serzh Sargsyan moving from president to the beefed-up role of prime minister

Peaceful mass protests have brought a watershed moment to Armenia, a small landlocked, post-Soviet nation.

An opposition politician who harnessed a revolution has lost a vote in parliament to become prime minister, but his movement has ousted Armenia's leader and raised hopes of free and fair elections.

When Nikol Pashinyan, 42, set off on his "My Step" protest march on 31 March from Armenia's second city Gyumri, sporting his trademark khaki T-shirt, only a couple of dozen people joined him, and they were mainly journalists.

By the time the MP and ex-journalist had reached the capital Yerevan on 13 April, thousands more had joined his movement.

For many Armenians this is the first time since independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 that they are able to believe in a better future.

When a barman in your hotel opens a cupboard and pulls out the national flag to show that he supports the protest movement, you know something is fundamentally changing.

So too for the 17-year-old school student skipping class to attend two weeks of rallies, because he wants access to a better education; the villagers in remote areas who feel that their voices are finally being heard; and the 12-year-old children blocking roads in an act of nationwide civil disobedience.

Nikol Pashinyan says only he can root out corruption in Armenia and lead it to free parliamentary elections

"We've tried to protest in the past so many times, but those protests did not lead to any changes and people lost hope," says Mher Gabrelyan, the barman with the flag. "It's different this time because at last there is someone helping to lead us."

How Armenia's revolution unfolded

13 April - Thousands take to streets of Yerevan as Nikol Pashinyan's 14-day protest march arrives

17 April - As daily protests continue Serzh Sargsyan is elected Armenian prime minister by parliament, eight days after his two-term presidency ended

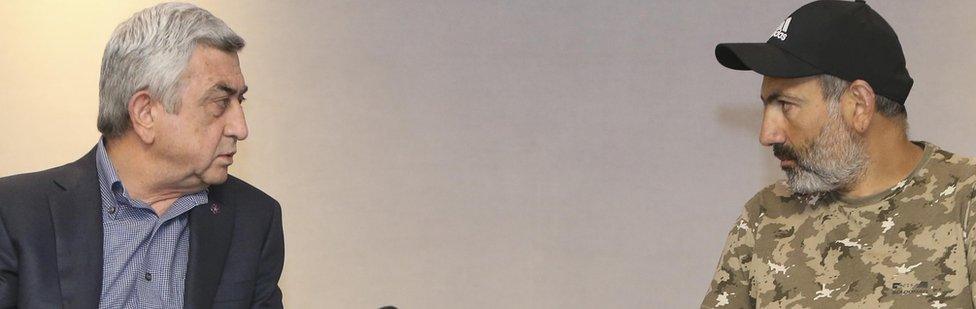

22 April - Nikol Pashinyan detained after talks collapse with Prime Minister Serzh Sargsyan

23 April - Nikol Pashinyan released and Serzh Sargsyan resigns, admitting "I got it wrong"; soldiers join protests

27 April - The man appointed acting PM, Karen Karapetyan, rejects new talks

29 April - Ruling party says it will not pick a candidate to challenge opposition leader

1 May - Ruling Republican party refuses to back Nikol Pashinyan

Serzh Sargsyan (L) refused to resign during talks with the protest leader

Why did the protests start?

It was in 2008 that Serzh Sargsyan came to power as president amidst violent suppression of anti-government protests in which at least 10 people were killed.

Fast forward 10 years. At the end of his second presidential term Serzh Sargsyan was about to become prime minister - a new and enhanced role, after changes to the constitution were passed by a 2015 referendum marred by widespread irregularities.

It was a miscalculation, because many Armenians regarded his move essentially as a third presidential term by the backdoor.

The BBC's Rayhan Demytrie meets protesters in Yerevan

Tens of thousands, mainly students and high-school children, poured on to the streets chanting "Make the step to reject Serzh".

"Most protesters are students who are unhappy about what's happening in the country," says protester and young IT specialist Ruben Elanakyan. "They are not the ones who grew up with Soviet propaganda, they are more free and that's why we are demanding our rights more freely."

Is this a rejection of Russia?

Much of what has happened here is unprecedented in any part of the former Soviet Union, including Russia's muted reaction to events.

Russia has a military base here and patrols the border with Turkey. Armenia is a member of President Vladimir Putin's Eurasian Economic Union and is part of Russia's regional military alliance. It has an unresolved conflict with Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh and depends on Russia for security.

Armenia's new president praises protesters

So Russia's stake in this country of 2.9 million people is significant.

But Nikol Pashinyan has met a delegation of Russian MPs and gone out of his way to pledge deeper relations with Russia, as well as with Armenia's neighbours, the EU, US and China.

Although Serzh Sargsyan was seen as an ally of President Putin, the leader of Armenia's self-styled Velvet Revolution says he has been promised that Russia will not intervene. That is in marked contrast with Georgia's 2003 Rose Revolution and Ukraine's 2004 Orange Revolution.

"It's not a colour revolution," says Fyodor Lukyanov, editor of the journal Russia in Global Affairs.

"Everybody understands that the roots of this crisis in Armenia are domestic - unlike several previous cases in the post-Soviet space, where international presence was pretty clear."

Russia knows that even if this pro-democracy movement prevails and Armenia embarks on a less corrupt chapter of its history, the country's economic and military dependence on Moscow will not change.

After Nikol Pashinyan's failure to secure the support of the ruling party, what happens next is unclear.

But he accused the party of waging "war against its own people" and said it had utterly destroyed itself.

- Published30 April 2018