Irish abortion result a seismic shift

- Published

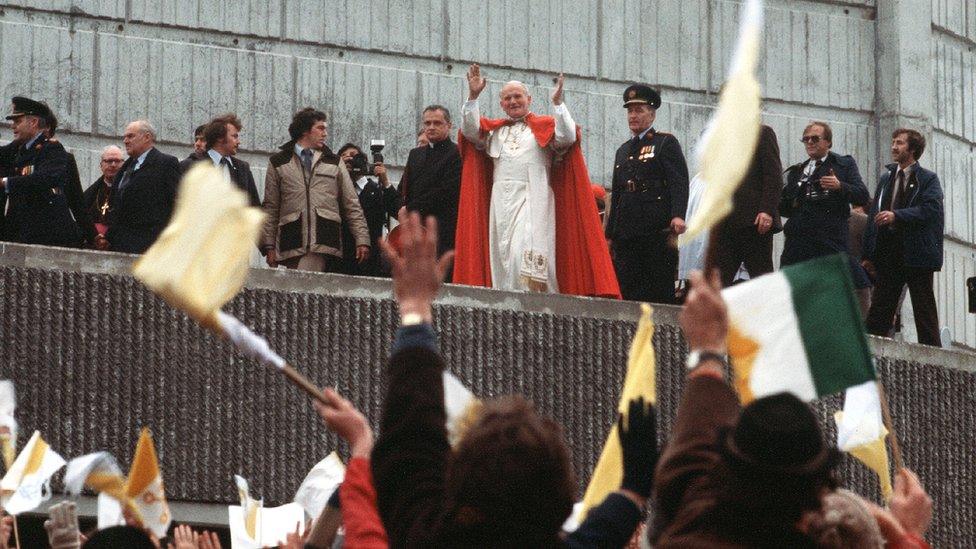

In three months time, Pope Francis will travel to Ireland and find a country undoing part of the legacy of a previous papal visit.

In 1983, four years after the triumphal visit of Pope John Paul II, the Irish people put the Eighth Amendment into their constitution.

The amendment gave equal rights to life to both the mother and the unborn.

Friday's vote, which paves the way for parliamentarians to liberalise abortion law, represents a seismic shift.

It also represents another sign of the societal change that has taken place in the Republic, coming just three years after the country officially passed the same sex marriage referendum with 62% in favour.

The Republic of Ireland, in the words of Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Leo Varadkar, will no longer export its abortion problem to Britain or import its solution.

It is estimated that nine women travel to Great Britain every day for terminations, while four women buy abortion pills over the internet without medical supervision, risking a jail term of up to 14 years.

The hopes of 1983 that Ireland could become a beacon light in the fight against abortion were never realised.

In the intervening years, more than 170,000 Irish women have left the state to end their pregnancies.

While hard cases may make for bad law, over the years they certainly changed public opinion on this most controversial and sensitive of issues.

A young woman leaves flowers at the Savita Halappanavar mural in Dublin

Controversial cases have included rape and incest, in which victims were told they were not entitled to a legal termination.

There was also the case of a brain-dead pregnant woman who was briefly kept alive against the wishes of her family until a court decided the foetus or unborn would not survive after a caesarean section.

And many women who were given a diagnosis of fatal foetal abnormality, where doctors believe the unborn will not survive outside the womb, have shared their stories of travelling to Britain to end their pregnancies.

The 2012 case of the Indian dentist Savita Halappanavar brought world attention to the country's laws.

She pleaded for an abortion in a Galway hospital as her health deteriorated because of sepsis, but was denied it because her life was not in danger at the time and there was still a foetal heartbeat.

By the time Mrs Halappanavar's life was in danger, it was too late.

Pope John Paul II was the first pontiff to visit Ireland in 1979

Opinion polls had suggested that those seeking the repeal of the Eighth amendment would win - but by nowhere near the overwhelming margin it turned out to be.

Just one constituency - Donegal - voted against repeal.

It was carried across the class divide and in every age group, apart from the over 65s.

But the biggest support was from young urban women.

Sinn Féin, the republican party has a well-known slogan - Tiocfaidh ár lá - which, in Irish, means 'Our Day Will Come'.

Now, there is a new Irish political slogan - Tiocfaidh ár mná - which translates as 'Here Come our Women'.

Sinn Féin leader, Mary Lou McDonald, and pro-choice abortion groups in Northern Ireland have said they would like to see both parts of the island allow pregnancy termination.

Northern Ireland is the only part of the UK that does not allow for unrestricted abortion.

Make no mistake this is a major setback for those, including the Catholic Church, who urged the people to save the Eighth Amendment.

The people voted knowing that if the there was a Yes vote, the government planned to introduce legislation later this year to allow for unrestricted access to abortion during the first 12 weeks of a pregnancy.

Despite the reservations of many about this proposal, they still voted for it unpersuaded by arguments that human life began at the moment of conception and that the right to life of the unborn took precedence over the health of the woman.

In 1983, the Catholic hierarchy played no little role in the passing of the Eighth Amendment.

However, in the intervening years, it has seen its standing greatly diminished with revelations about bishops not reporting paedophile priests to the civil authorities.

There have also been revelations about what happened in mother-and-baby homes run by nuns for unmarried pregnant women.

In one notorious case in Tuam, County Galway, the bodies of infants were discovered in an unmarked mass grave last year.

A state-appointed inquiry said investigators recovered "significant quantities" of human remains at the site, many of which dated back to the 1950s.

There have also been allegations of forced adoptions, in some cases in exchange for money from rich Catholic Irish-Americans.

So, it was little surprise then the bishops played a less prominent role in a referendum about what they see as being about life and children' rights.

- Published26 May 2018

- Published26 May 2018