What is Italy's political crisis all about?

- Published

Five Star leader Luigi Di Maio: A media frenzy over Italy's future

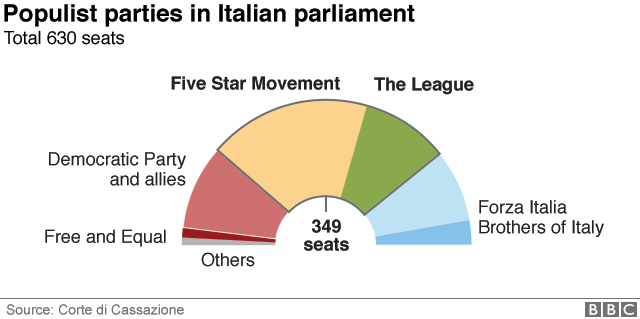

Italy is embroiled in a power struggle between Eurosceptic populists - winners of the March election - and pro-EU establishment politicians.

It took weeks of negotiations for a populist coalition to take shape, but the president has controversially vetoed it, so Italy is now back to square one.

Now the country faces an interim government - not yet in office - before fresh elections.

What makes this a crisis?

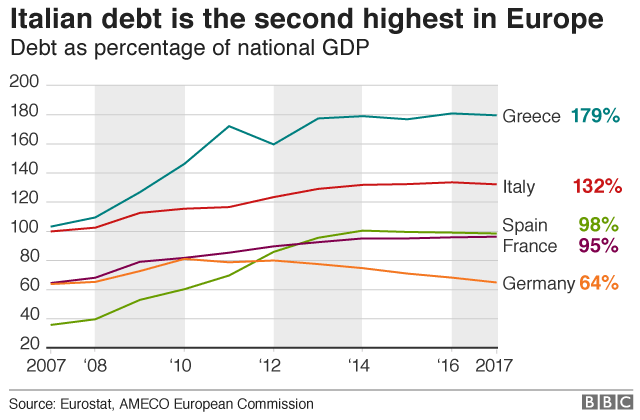

Italy's economy - the eurozone's third-largest - has been anaemic for years.

The EU and global markets are watching nervously. The eurozone's 2010-2011 debt crisis was patched up, but not solved.

President Sergio Mattarella's rejection of the populists' choice for finance minister - Prof Paolo Savona - exposed tensions over the euro. The 81-year-old economist had advocated a "Plan B" for Italy to exit the euro.

The anti-establishment populists - the Five Star Movement (M5S) and the League - were enraged by President Mattarella's veto.

The new prime minister-designate, Carlo Cottarelli, is an International Monetary Fund (IMF) veteran close to Brussels technocrats, solidly pro-euro and pro-austerity. He is known in Italy as "Mr Spending Review" and "Mr Scissors".

How does it rate on the scale of Italian crises?

Pretty high. But Italy is no stranger to political turmoil. It has had 64 governments since World War Two.

M5S leader Luigi Di Maio called for President Mattarella to be impeached. League leader Matteo Salvini suggested that Germany was behind the president's veto; but Italy was not a "colony", he said.

Frustrated populists: Five Star Movement's Luigi Di Maio (left) and the League's Matteo Salvini

This stand-off is new territory for Italy, because populists won an unprecedented popular mandate to govern - the first time they have achieved that since WW2.

So the proposed caretaker government will have to tread carefully. Mr Cottarelli says new elections will be held in early 2019, or after August if he fails to survive a confidence vote. The latter appears the most likely.

New PM in for a rough ride - Italian press

Italian papers predict that Carlo Cottarelli will have a tough time forming a government, and that once in power he will struggle to execute his plans.

The leftist Manifesto newspaper says: "It is not easy to find people ready to stay in the government for several months, without trust in parliament, and crucified by the two strongest parties ready to open fire."

The centrist daily Corriere Della Sera suggests that Mr Cottarelli will be a "steady hand at the wheel, in market waters that promise to be rough", but that it will be difficult for him operate because he will be "a prime minister without trust".

Read more on the challenges for Italy:

Some Italians already suspect an EU-engineered plot, after what happened in 2011. Back then Italy was getting punished by global markets - it risked default as interest rates on its government bonds soared. Then-Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi was ousted and replaced by former EU commissioner Mario Monti.

Is the president's position shaky?

Not immediately. Mr Di Maio's call for his impeachment is unlikely to get majority support in parliament. The constitution envisages impeachment only for "high treason" or for "acting against the constitution".

President Mattarella has certainly shown that his job is much more than ceremonial.

It is up to him to appoint the government. But rejecting the M5S-League team was politically risky. Their anti-establishment appeal to voters may grow even stronger now, as the interim government is accused of doing Brussels's bidding.

What does it mean for the euro?

Italy has a government debt burden of €2.3tn (£2tn; $2.7tn). That is a colossal 132% of GDP and the second-highest debt level in the EU, after Greece's.

The League's Matteo Salvini insists that "nobody ever thought of exiting the euro - it wasn't in our manifestos, nor in Savona's manifestos".

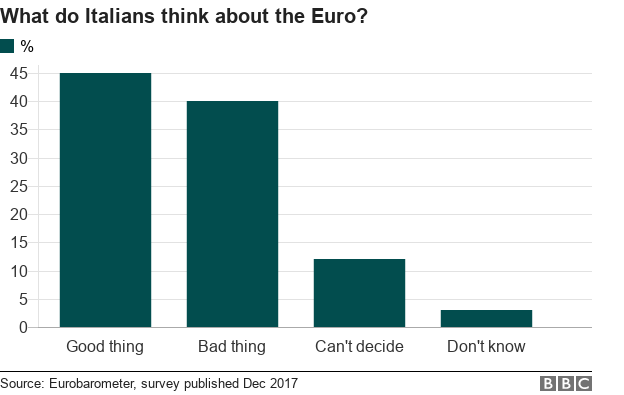

His M5S partners dislike the euro but no longer plan to hold a referendum on the single currency.

However, the euro is very much on the populists' agenda, external, because they promise a renegotiation of key eurozone agreements, such as the Stability and Growth Pact, external and the Fiscal Compact, external. Those pacts commit states to budget discipline and strict targets set by Brussels.

They want to shift EU priorities away from free-market liberalism, towards social welfare.

They plan to pump billions more euros into social policies in Italy, such as boosting pensions and benefits for the poor.

Opinion polls suggest that the League's popularity has risen since the election. So another election within months might give the League - right-wing and anti-immigration - a commanding position.

The latest quick fix in Italian politics is unlikely to reassure the rest of the EU.