World Cup fails to quell Russian anger over pension reform

- Published

Among the slogans was one directed at President Putin: "You give him 76% in the election, and at 76 you get to retire"

Euphoric Russians took to the streets when their team advanced to the quarter-finals of the World Cup by beating Spain.

But hours before Sunday's match, in 38 Russian towns and cities, there were protests at government plans to raise the retirement age for men and women.

In the Siberian city of Omsk 3,000 people turned out, according to the organisers.

"Help the state, die before your pension," read one home-made placard. "The government must go," read another.

You would not have seen them in any of the 11 World Cup cities, because of a ban on demonstrations for the duration of the tournament.

Under the new plan, to be implemented gradually from 2019, the retirement age for men will be increased by five years to 65.

Women will have to work another eight years from 55 to 63.

The scenes were very different in the centre of Moscow hours later when Russians celebrated their knockout victory over Spain

Unusually for Russia, protesters in Omsk were from all sides of the political debate.

Communist Party red flags and nationalist banners flew side by side, and opposition supporters joined in too.

Read more Russian World Cup stories

"I'm here because the government is stealing from us," said Ivan Vasilievich, a pensioner in his 70s who supplements his pension with a job as a security guard.

"My granddaughter and her children couldn't survive without the money I bring in."

"Enough" reads a placard held by a protester in Ivanovo north-east of Moscow

That some Russians are prepared to tear themselves away from the football, and take to the streets in a summer heat wave, is an indication of how angry they feel.

It is not just because their government wants to raise the pension age for the first time since Stalin, but also because of how it has all been handled.

Burying bad news?

The televised announcement by Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev coincided with the opening of the tournament on 14 June, prompting criticism that the government was burying bad news.

Russia's prime minister (2nd right) was all smiles, unlike Spain's King Felipe VI (left), as they watched Russia qualify for the quarter-finals on Sunday

And it came despite past promises from President Vladimir Putin that the pension age would never be raised on his watch.

The prime minister says the decision was motivated by the fact that Russians are living longer and leading more active lives.

"There are more opportunities to continue their careers," he told a cabinet meeting. "We have 12 million working pensioners: that's almost a quarter of all pensioners."

Why Russia needs to raise the pension age

Most economists and many Russians agree there is a problem. The population is getting older and the state is spending more and more on pensions.

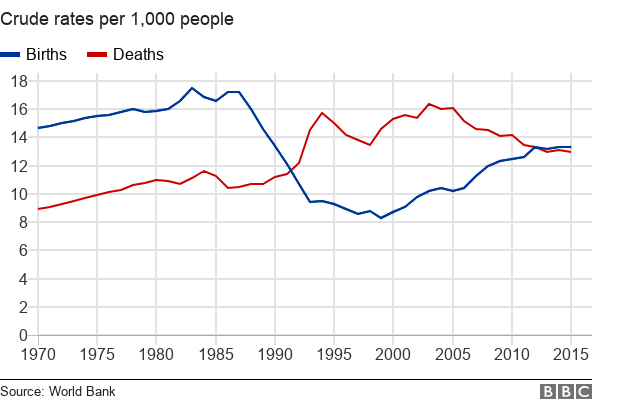

After the economic chaos of the early 1990s, Russia's population plummeted. The birth rate has since shown some signs of improvement, but it is not happening fast enough.

Based on current trends, 20% of Russians will be over 65 by 2050, says the UN.

President Putin has just signed a new bill on pension spending, envisaging a deficit of more than 265bn roubles (£3.1bn; $4.2bn) in 2018. That's 1.6% of the entire state budget expenditure.

It is clearly not a sustainable situation, especially in tough economic times.

Russia in numbers

Population: 143.5 million

Unemployment: 5.2%

Economic growth: 1.5% (in 2017)

Source: OECD; Tass

While economists agree the reforms will help balance the books, many question why they were not implemented earlier when the economy was in better shape.

"Putting off an unpopular but inevitable measure… shows an unforgivable lack of seriousness by the government," say two top economists from Moscow's Higher School of the Economy, Ilya Kashnitsky and Vladimir Kozlov.

Although the reforms won't come into full effect until 2028 for men and 2034 for women, ordinary Russians worry about the impact.

"They haven't given us more years of work, just more years of poverty," said one banner at the Omsk protest.

Is Russia equipped for a higher retirement age?

Moscow accountant Larisa Grigorieva, 57, retired two years ago and has tried and failed to find work ever since, struggling to compete in a changing market.

"I'm not getting any responses. They see you're 57 and no-one's interested," she says.

Russians on warm World Cup atmosphere: 'It's splendid, it's great'

Unless workers of Larisa's generation are given suitable training, many are likely to end up in the shadow economy with lower pay and few rights.

The other problem for many Russians is the worry that they will not even live to retirement age.

That is because average life expectancy for men in 15 Russian regions is currently lower than the new retirement age of 65. Most of these areas are in the Far East but some are in the west.

Could Putin be hit by pension row?

So far the president has refrained from comment. His spokesman says he has not even been involved in the discussions, leaving some to speculate he might intervene at some point.

But two recent sets of polls show Mr Putin's popularity has taken a dent.

According to state pollster VTsIOM, his approval rating fell by 14 points from 78% to 64% in the two weeks since the reform.

Far from enjoying a World Cup bounce, Mr Putin's ratings have gone down since the tournament began

And the independent Levada Centre published a survey on Tuesday showing trust in the president had dropped below 50% for the first time in five years.

"I wouldn't make a big thing out of it," said his spokesman.

At the Omsk protest, many seemed reluctant to blame the president personally.

"Please stop Medvedev!" read one placard. But not everyone agreed. "Prosecute Putin and Medvedev," said another.

When the World Cup ends, so does the ban on protests in host cities. That is when the next chapter in this row will unfold.

- Published1 July 2018

- Published12 March 2018