Europe's copyright plan: Why was it so controversial?

- Published

Memes usually use copyrighted images - like this one from BBC Three's #HoodDocumentary

It's rare that a vote in the European Parliament prompts widespread outrage by social media users, academics, and technology leaders all at once.

But as the EU tried to transform its copyright laws for the digital age, that's exactly what happened - and MEPs rejected the directive on copyright.

So what was the problem? It all came down to just two small parts of the proposed text.

Article 13, critics claimed, would have made it nearly impossible to upload even the tiniest part of a copyrighted work to Facebook, YouTube, or any other site.

That would have meant no more stills from movies, no more song remixes, and the danger of constant blocks by automatic systems getting it wrong.

Article 11, the other controversial part, might have made linking harder because it would have given news publishers better control over their content.

All this led to more than 800,000 signatures on a petition against the proposals by the time the vote came - and MEPs, it seems, heard the outcry.

But the EU commissioner behind the proposed law had rubbished critics' objections, and it had the support of newspapers and many top musicians.

So what, exactly, were the concerns?

Article 13 - the 'upload filter'

Article 13 was all about the "use of protected content" by sharing services.

In a nutshell, it said that any website which "gives the public access to copyright protected works... uploaded by its users" had to get permission from whoever owned the copyright - probably through a licensing agreement.

If it didn't have that permission, the site would need to block it.

This seems straightforward - that copyright owners (including ordinary people who take a great photo, for example) should be paid for their work, and have control over where it appears.

Many opponents agreed that this was a good idea. But the proposals put the onus on websites to check everything uploaded by users. That's impossible for humans to do.

On YouTube, for example, 400 hours of video are uploaded every single minute - a volume that can't be managed by real people.

The proposed law allowed for exemptions for small businesses, but everyone else would almost certainly have needed to use an automatic system.

And that is potentially fraught with problems.

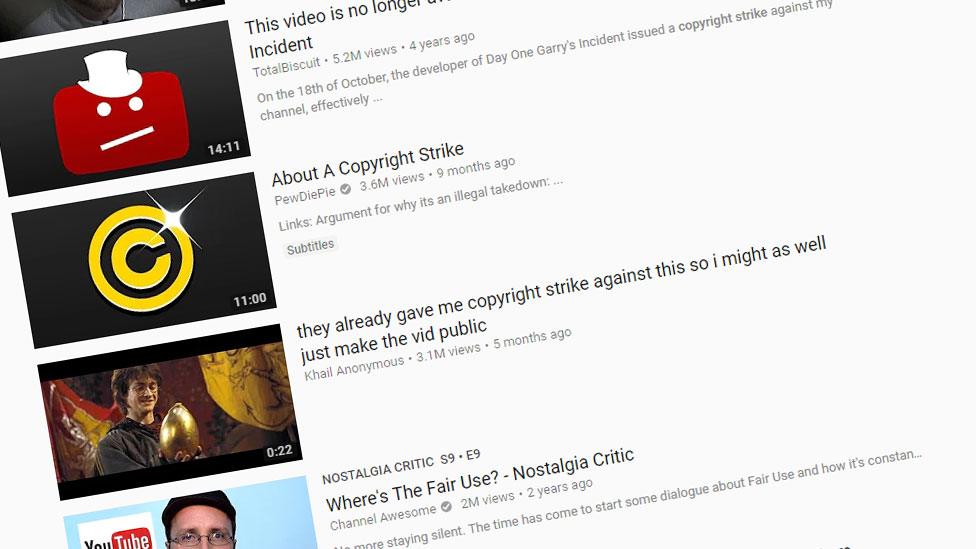

YouTube's own platform is full of complaints about its system from its creators

YouTube already has a system to scan for copyright infringement in uploaded videos automatically. But there are innumerable examples of the system getting it wrong, including:

One musician recorded 10 hours of "white noise" - like television static - and got five copyright claims

In 2012, Daniel Unedo made a video about salad in a field, external, and had a copyright claim made for the sound of birds chirping

Popular Irish YouTuber Clisare allowed RTE to use one of her videos, external - and last week had the original version blocked automatically

This automated copyright system has cost YouTube at least $60m.

Critics of the proposed EU copyright rules predicted that similar expensive, imperfect systems would need to be rolled out by every website if Article 13 became law.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

And that could have affected more than just video. There were fears Article 13 could place a ban on memes: those popular, recognisable images (usually from films or TV) with text emblazoned across it to express ideas.

Julia Reda, an MEP from the German Pirate Party, wrote a widely shared blog post attacking the proposal, external, which she described as "upload filters, shoddily hidden".

"Article 13 applies to every platform with an upload form and every app with a 'post' button," she argued. "These filters are bound to block legitimate acts of expression... because they can't tell apart valid uses like quotation from infringement."

And getting a licence for every type of content that exists from every publisher would be "plainly impossible", she said.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

She's not alone. Dozens of influential technology leaders, including inventors of key internet technologies Vint Cerf and Tim-Berners Lee, rallied against Article 13, external.

Article 13 "would mandate internet platforms to embed an automated infrastructure for monitoring and censorship deep into their networks," a joint letter said.

Those in favour of the new rules pointed out that many exemptions existed in the directive for legitimate use of material, and that there would be a complaints process.

It also had the backing of major musicians like Sir Paul McCartney, who want to see their music better protected.

But the way EU directives work means that every single country would have implemented the rules in national law the way it saw fit - and it wasn't clear how each country would define what was acceptable and what was not. Many critics felt that internet services which operate across borders would be likely to play it safe.

And unlike blocked websites, which can be circumvented using a VPN (Virtual Private Network), these checks would all have been done by on the systems of each website - and it's not clear how easy such checks would be to get around.

Article 11 - the 'link tax'

The other controversial part of the proposed law was about the "protection of press publications".

The intent was to protect newspapers and other outlets from the use, without payment, of their material by internet giants like Google and Facebook - again, something many people agreed was a good idea.

But the proposal said it was up to each individual country to decide what an "insubstantial part" of a news report would be - and anything else would need a licensing agreement.

The fear was that this could lead to problems with even the tiniest sentence fragments being used to link to other news outlets - something that many news outlets, including the BBC, does every day.

Article 11 could, critics said, cause huge problems for links on platforms like Facebook, which pulls in a "snippet" and thumbnail of the article to give readers some idea what the story is about.

The proposals made an exception for private, individual use - but it could be argued that anything on Facebook (or other sites that make money) is a "commercial use".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Wikipedia, one of the world's largest websites, has been particularly vocal about the issue.

Its co-founder Jimmy Wales took to social media campaigning against it, external, writing on Reddit that "Articles 11 and 13 are nightmares".

On another Reddit thread, Mr Wales wrote: "Publishers, I predict, will instantly cave in and give Google and Facebook free licences... but smaller providers - dead.

"They don't have the clout to get permission to use a snippet or thumbnail, and they can't afford to pay."

For Wikipedia, its campaigning paid off - the final version of the proposed law included an exemption for "online encyclopaedias" and other non-profit purposes.

But the organisation continued its campaign, arguing that "our overarching mission is heavily dependent on a free and open internet ecosystem".

What happens next?

The proposed directive is due to be revisited in September, with a European Parliament debate and possible changes.

It's not yet known whether Articles 11 and 13 will be removed or amended.

If eventually adopted by the European Parliament, the directive will be sent to the EU Council, which also has to approve it - a process that could take months.

Usually, the Parliament and the Council agree - but if they don't, they'll form a committee to try and reach consensus.

Once they've both agreed and approved the directive, it has to be put into law by every member state on a country-by-country basis, in a process the EU calls transposition.

That can take a year or two, as each country navigates its own legal and parliamentary system.