Barcelona attack: The jihadists and the hunt for a second gang

- Published

A neighbour had just walked past when an explosion tore through a small, white house in the Spanish coastal town of Alcanar last August.

Debris was flung hundreds of metres by the force of the blast and the bodies of two men landed in nearby gardens. A third man who had been on a roof terrace talking on his phone survived.

The next day a van attack was launched on pedestrians in Barcelona's central tourist avenue, Las Ramblas. Hours later there was another attack, in Cambrils, a coastal town. Sixteen people died and more than 130 were injured.

Catalonia had come under attack from a jihadist gang of 11 people.

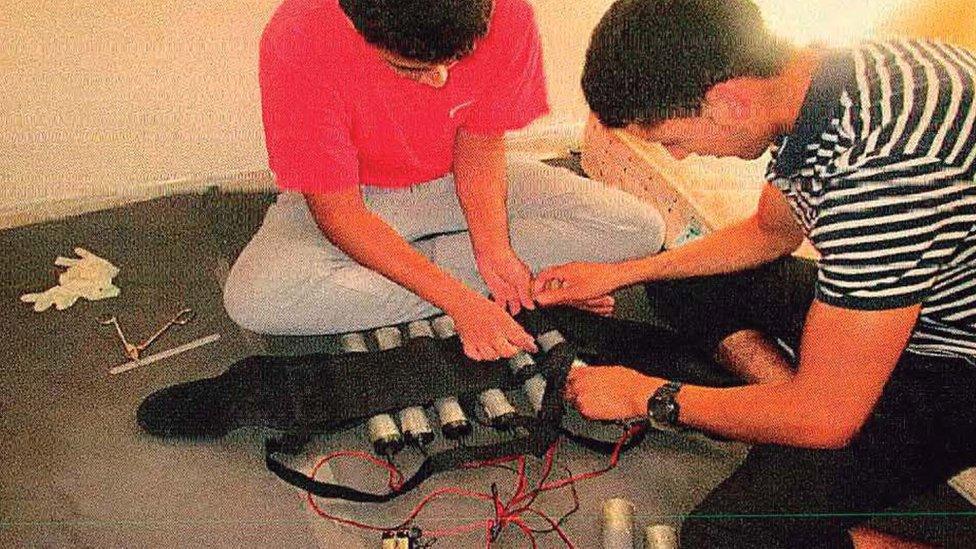

Youssef Aalla and Younes Abouyaaqoub preparing an explosive belt at a house in Alcanar

Investigators believe they had planned to target Barcelona's Sagrada Familia and the Camp Nou stadium, home to Barcelona football club. The Eiffel Tower in Paris was another target.

The Alcanar blast late on 16 August had changed all that and the key figure, Abdelbaki Es Satty, lay dead in the rubble.

But this is also a story of missed clues and intelligence failings, because Es Satty had been known to the authorities for years.

And the BBC has learned that his gang of extremists was plugged into a network that, according to a surviving cell member, could have included another imam with a second cell of eight or nine young men in France.

A year on, investigators in France have requested information from 10 countries and are still trying to break up that network and identify a possible French cell.

Catalonia's head of counter-terrorism believes the plot could have been masterminded by someone outside Spain.

The story of Es Satty's gang

As neighbours emerged from the destroyed buildings in Alcanar, no-one considered an extremist link. The bodies of Es Satty, 44, and 22-year-old Youssef Aallaa were identified.

The house in Alcanar was all but destroyed by the explosion

"The strongest hypothesis was that it was a drugs lab," said firefighter Jordi Bort, who was among the first on the scene.

It was not until emergency services had dug through the rubble the next day that the full picture emerged.

There was a second blast, almost as large as the first. Nine firefighters were injured.

They had stumbled on a bomb factory containing more than 200kg (440lb) of explosives. Much of it was extremely unstable, designed to cause multiple deaths.

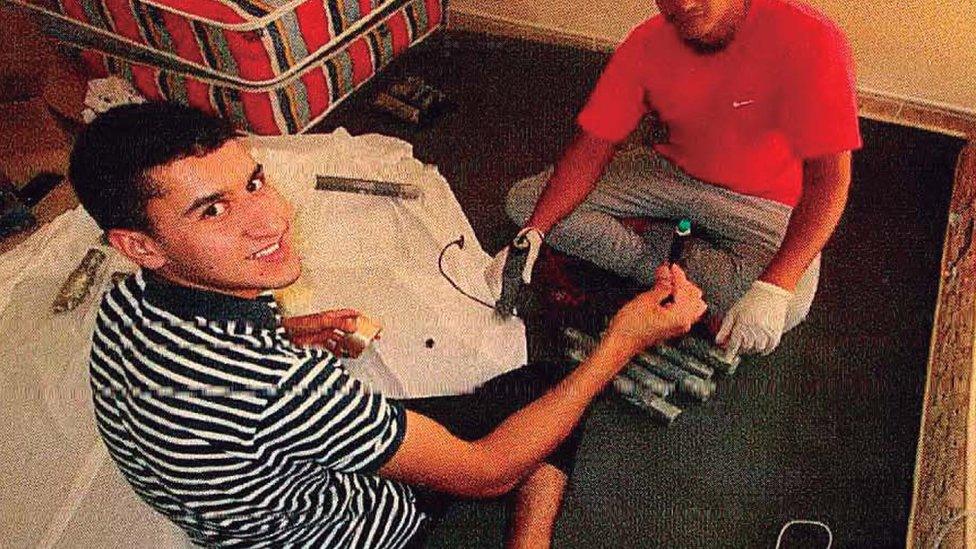

Younes Abouyaaqoub and Youssef Aalla posing as they prepare hand grenades at a house in Alcanar

There were canisters, nails, large quantities of acetone, hydrogen peroxide, bicarbonate and detonator switches - all the ingredients to create TATP (triacetone triperoxide) explosive.

They also found grenades and suicide vests.

Investigators only discovered later, from material recovered from digital cameras, computers and mobile phones, that the men had planned to use these explosives at some of Europe's biggest landmarks.

The attacks

It was on the afternoon of 17 August that 22-year-old Younes Abouyaaqoub jumped into a rented white van and zig-zagged down Las Ramblas at high speed, careering into pedestrians along the packed avenue.

Witnesses said the driver had tried to hit as many people as possible.

Many were knocked to the ground while others fled for cover in nearby shops and cafes.

Abouyaaqoub killed 13 people and injured more than 130 before fleeing on foot. He then hijacked a white Ford Focus, killing the driver. A German woman injured on Las Ramblas later died, taking the death toll to 15.

Eight hours later, in the early hours of 18 August, five men drove to Cambrils, 100km (62 miles) down the coast from Barcelona. They were the Barcelona attacker's brother, Houssaine Abouyaaqoub, along with Moussa Oukabir, Said Aallaa and brothers Mohamed and Omar Hychami.

Their black Audi A3 car ploughed into pedestrians at the seaside resort and overturned before the gang got out wielding knives and an axe. A Spanish woman was killed and several others wounded.

The attackers were wearing fake suicide vests adorned with plastic bottles to create panic. The vests also ensured they would be shot by police and, in their eyes, die as martyrs.

Barcelona attacker Younes Abouyaaqoub was still on the run. His journey finally came to an end on 21 August in a field west of Barcelona. Police were tipped off by the public and Abouyaaqoub, wearing a fake explosives belt, was shot dead.

The young men behind the attacks had claimed 16 lives.

Who was behind these murders?

Normal boys who turned to violence

Ninety minutes' drive inland from Barcelona, on the edge of the Pyrenees, lies the picturesque town of Ripoll. Surrounded by pine trees and mountain rivers, this is where most of the Catalan terror cell grew up.

They were all first- or second-generation immigrants from Morocco and most were childhood friends who went to the same school. They included four sets of brothers.

By all accounts they were normal kids who played in the local football teams, went to after-school clubs and took part in hiking trips.

Cambrils attacker Houssaine Abouyaaqoub was known as Houssa and was part of the local football team.

When they were boys they played football together

Social worker Nuria Perpinya helped some of them at a school homework club.

"They would go there after school to use the computers because they didn't have a computer or any internet connection at home," she said.

"They were like all the kids," wrote Raquel Rull, the mother of one of Houssa's friends, in an emotional letter published after the attacks.

"Like the one you see playing in the square, or the one who carries a big school bag filled with books, or the one who says 'Hi' and lets you go first in the supermarket queue, or the one who gets nervous when a girl smiles at him."

The youngest member of the cell, Houssaine Abouyaaqoub, was known to friends as Houssa

Apart from the older Es Satty, only Driss Oukabir, the eldest of the boys, was known to the authorities. He had a criminal record for robbery, sexual assault and domestic violence, but even then his conduct had attracted little attention.

Driss Oukabir "enjoyed life" with his girlfriend and his dog

On leaving school, most of them had gone to work in local factories, cafes and restaurants.

How Es Satty groomed a terror cell

Then Abdelbaki Es Satty arrived and started working at one of the town's two mosques, saying he was an imam.

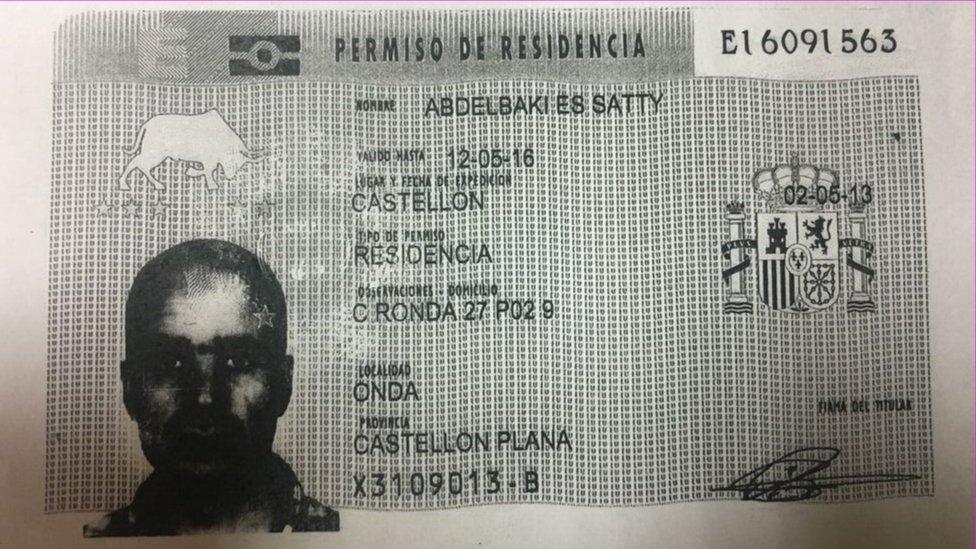

Born in Morocco's Rif mountain region, he had come to Spain in the early 2000s and had been in and out of prison until he was brought to Ripoll by a Moroccan woodcutter during the spring of 2015.

Abdelbaki Es Satty arrived in Ripoll in 2015

For Ibrahim Aallaa, whose sons Said and Youssef were killed at Alcanar and Cambrils, Es Satty was a "bad influence" and he did not like him.

He had twice visited the house uninvited when he thought Ibrahim was not at home. Said had been working in a local cafe and Es Satty said he should stop as it served alcohol and pork.

Youssef had been told to stop working during Ramadan.

Es Satty's flat overlooked Ripoll

"Es Satty's belief was too strict," Ibrahim said. "It was an interpretation of Islam that I didn't like. I told my boys too. I didn't want them to go to the mosque and I didn't talk to Es Satty."

By January 2016, Es Satty had left Ripoll in search of new opportunities.

He went to Belgium to preach at a mosque in Diegem, outside Brussels. He had told leading members of the community he was an informant for the Spanish intelligence services.

Hans Bonte, mayor of Vilvoorde in Belgium, has spoken of intelligence failings related to the case

"They didn't trust him, they asked him for some papers to convince them that he actually was an imam," said Hans Bonte, mayor of Vilvoorde. "But he didn't have a record, so he couldn't give them."

The head of the mosque went to the police and Es Satty's details were put on a national database by a local police officer.

The case was due to be discussed by local and national security services, but the officer heard nothing back.

The Belgian officer also approached a Catalan counterpart he knew but nothing came of that either.

From plot to attack

Despite local authorities twice flagging up their concerns, Es Satty returned to Ripoll in April 2016, soon after the Brussels bombings.

"There was a lack of information exchange between Catalan police and the federal Spanish police and that gave a lot of tension between Catalan and Spanish authorities," Mayor Bonte said.

Es Satty was to return to Brussels several times.

Back in Ripoll, Es Satty began work at the town's second mosque.

A year before the events in Barcelona, friends of the Ripoll cell members began to notice a change in their behaviour. They stopped wearing branded clothing and visited the mosque more frequently.

"They closed themselves up a little," said one.

"They were missing something - a spiritual void, a religious void"

They also made regular trips to the bomb factory in Alcanar. One of the most frequent visitors was Younes Abouyaaqoub, the Barcelona attacker. The house was registered in his name and in Youssef Aalla's.

In documents seen by the BBC, the cell searched online for chemistry manuals, various IS leading figures, bomb-making manuals and possible targets to attack.

In order to fund the purchase of explosives and their travelling, they stole money from their places of work, and sold gold and jewellery in small towns on the coast.

By now, older members of the Ripoll gang were travelling abroad and material found on computers and phones has revealed how the cell was linked to people known to authorities across Europe.

There were various trips to Morocco to visit friends and family, especially ahead of the attacks, and one visit to Austria. Es Satty repeatedly travelled to Belgium too, and was last seen there two months before the Catalonia attacks.

But there were two other trips that investigators found particularly interesting.

In December 2016 Youssef Aallaa and Mohamed Hychami flew to Basel in Switzerland and stayed at the Olympia Hotel in Zurich. Their aim was likely to discuss logistics or financing with figures connected to a controversial An'Nur mosque. The mosque in Winterthur, which has since shut, denies such claims.

One week later, those two men joined Younes Abouyaaqoub - who would eventually become the Ramblas attacker - in Brussels.

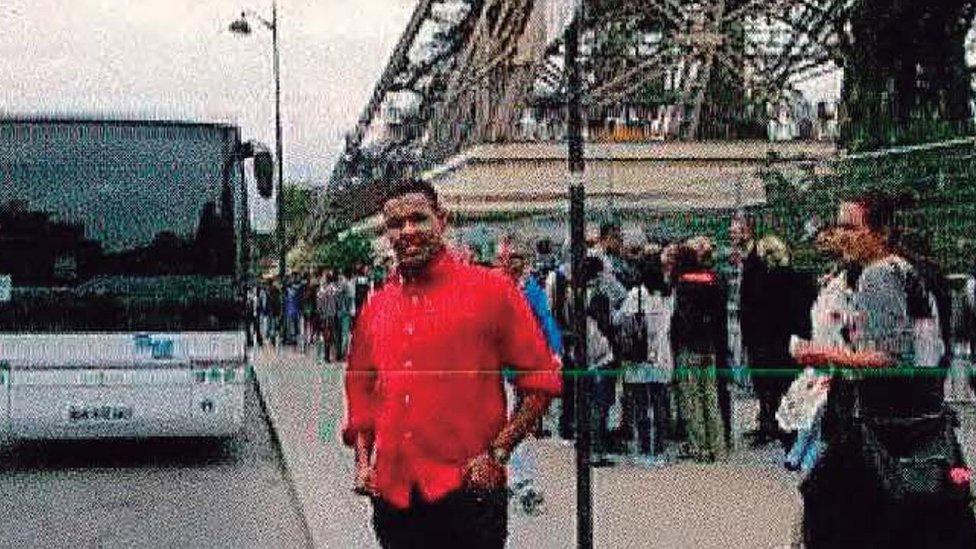

Omar Hychami beside the Eiffel Tower in Paris

And days before the Ramblas attack, the man who carried it out, Younes Abouyaaqoub, went to Paris with Omar Hychami. They took the Audi which Hychami was in when it rammed pedestrians in Cambrils.

On 11 and 12 August the men's phones were tracked to central Paris as well as the city's Malakoff and Saint-Denis areas. They called contacts who were using pay-as-you-go Sim cards.

Who was in charge?

Investigators believe the Paris trip was part of a mission to find targets for a second cell of jihadists. That target was to be the Eiffel Tower.

The question is whether Es Satty and the Ripoll cell were part of something much larger and linked to wider extremist networks and plots in Europe.

"We think there is some brain outside Spain," says Manel Castellvi, head of counter-terrorism in Catalonia, "maybe in Europe, or maybe in a conflict zone, who convinced them to carry out this attack."

Senior police officials believe an outside mastermind was involved.

While the TATP explosives they amassed in Alcanar were relatively easy to get hold of, Mr Castellvi believes the quantity they had, as well as their ability to make the explosives, suggests "someone with important knowledge could have given information to the cell".

The BBC has also learned that Es Satty had booked a flight from Barcelona to Brussels for October 2017 - suggesting Es Satty was not planning to kill himself like the others.

Why did they miss Es Satty?

Es Satty had been known to intelligence agencies for years, but decisive action was never taken.

When the alarm was raised in Brussels in 2016, there was a failure to communicate between Belgium and Spain, and within Spain itself.

But the failings go back much further than that.

Es Satty was on their radar for links to jihadists as early as 2005.

He was living in Vilanova i la Geltru, a coastal town near Barcelona, and spent time with an Algerian man called Belgacem Belil. The pair were connected to a network known as the Vilanova cell.

Abdelbaki Es Satty's phone was tapped twice by Spanish authorities

Belil became a suicide bomber in Iraq, killing 28 people in November 2003.

Members of the cell were investigated for sending people to Syria and Iraq and were connected to people involved in the 2004 Madrid bombings. However, initial convictions handed down to them were quashed.

Then, in 2005, Spanish authorities sought approval to tap Es Satty's phone. They believed he could be acting as an intermediary with individuals connected to militant group Ansar al Islam. Not finding enough evidence, the phone tap was lifted but, at some point, his name was added to a European database of people who support terrorism.

In 2010 he was jailed in Castellon, south of Barcelona, for transporting cannabis between Morocco and Spain.

While in prison, he was approached by Spain's National Intelligence Centre (CNI), most probably as a possible informant, but he was deemed unreliable.

However, he was considered interesting enough for his phone to be tapped when he left prison, the BBC has learned. The CNI wanted to know if he was still in touch with extremists, but again the wire-tap was halted because a judge decided it had failed to yield relevant results.

The warning signs were there and opportunities were missed.

Abdelbaki Es Satty took several years to move from the fringes of extremist Islam to become the ringleader of a murderous cell in rural northern Spain.

Lessons have to be learned about exchanging information, says Manuel Navarrete, Europol's head of counter-terrorism.

"Barcelona showed that we need to think in a different way about local actors, a local cell that became quite sophisticated."

Credits: Investigative Producer Antia Castedo and Faisal Irshaid, Executive Producer: Jacky Martens; Design by Zoe Bartholomew and Prina Shah.

- Published22 August 2017

- Published27 August 2017

- Published18 August 2017