Scallop wars: Could Brexit calm troubled waters?

- Published

Some trawlers were damaged in the overnight fracas

British and French fishermen have clashed in the Channel, over alleged "looting" of the scallop fishing grounds there by British boats. Tense exchanges were filmed on Tuesday, off the coast of Normandy, after years of carefully managed truce between the two sides. What lies behind the fresh tensions, and what impact will Brexit have on relations between them?

In times of cross-Channel tension, it's been a handy and well-worn reflex in some quarters to blame the meddlesome bureaucracy of the EU - its agricultural subsidies; its detailed trading standards; its fishing quotas.

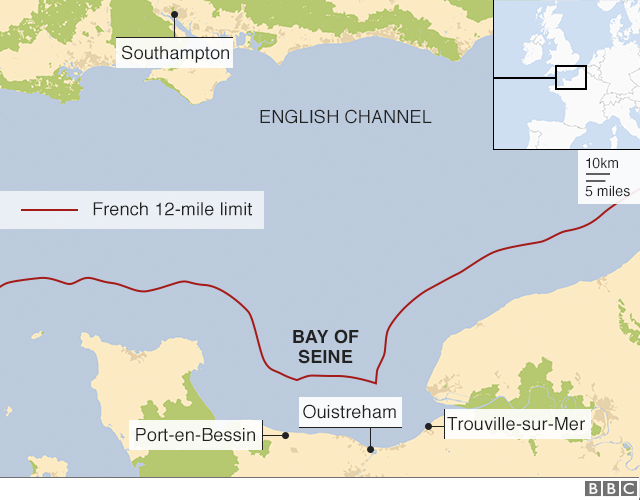

For more than a decade, the friction between British and French fishermen around the Bay of Seine, off the coast of Normandy, has been over scallops.

The French fishing industry is bound by an agreement with its government in Paris not to fish for scallops in the area between May and October, in order to conserve fish stocks. The British - who are also allowed to fish the area under EU access rights - are under no such restrictions from their own government.

Et voilà: an ongoing battle that's been wearily termed "the scallop wars".

For the past few years, a carefully constructed truce has kept the peace over this watery battlefield. The British agreed to ban their larger fishing vessels from the area until October, in keeping with French restrictions, on the understanding that smaller British boats could fish there all year round.

But with the big boats out of the way during the summer months, the Regional Committee for Maritime Fishing in Normandy says that the number of smaller boats coming across the Channel is growing. This year, they asked that all British boats stay away from the scallop fishing grounds until they could share the catch, from October onwards.

But smaller British fishermen are already feeling hard done by, because the vast majority of their EU fishing quotas go to larger British industrial fishing fleets, and many struggle to make a profit. Scallops, on the other hand, are not restricted by standard EU quotas. Larger vessels have limits on the number of days they can fish for them, but boats under 10m (32ft) have an open invitation - a small but important symbolic advantage.

So, their answer to the new terms of the truce? Non.

With no gentlemen's agreement in place, British vessels have had free rein to stir up the stormy waters of Normandy's scallop grounds. And in the early hours of Tuesday morning, the French took things into their own hands.

British fishermen said they had been surrounded and had rocks and metal shackles thrown at them

So far, no-one has been hurt, but the dispute remains unresolved. Both sides have agreed to meet, to try to find a solution.

One local fisherman told Le Monde newspaper that a hard Brexit would solve it once and for all - by denying the British automatic access to fish in EU waters.

But the rules restricting French scallop fishermen in the Bay of Seine have nothing to do with the EU. And even if their British rivals leave the bloc, France's fisheries ministry points out, that area is open to other EU members who have the freedom to fish there all year round.

Even for British fishermen - who are reported to have voted overwhelmingly for Brexit, with the aim of regaining control over their own national fishing grounds - Brexit may not be the cure-all.

EU vessels will no longer have automatic access to British fishing waters after Brexit, but the war over quotas between big industrial vessels and local fishermen is an internal British one.

It's the authorities in London, not Brussels, who set the rules under which industrial fishing companies dominate the market, and allow the "leasing" of fishing quotas by big companies, while some other EU governments, like France, do not.

Brexit may look like a handy solution for fishermen on both sides of the Channel, but - as one journalist put it recently - it could well be a red herring.

- Published29 August 2018

- Published21 August 2018

- Published21 March 2018

- Published20 June 2018

- Published23 February 2018