Slovenia politician's masked militia sparks alarm

- Published

Video of the militants appeared on Facebook

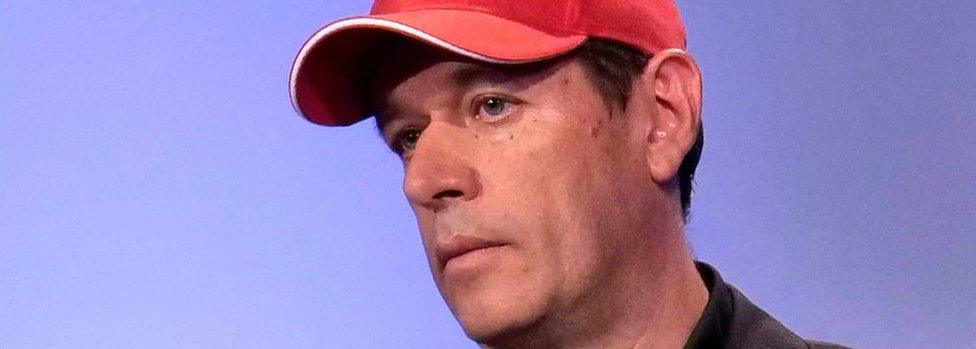

Slovenian President Borut Pahor has expressed concern after social media images revealed a masked armed group led by an ex-presidential candidate.

Fringe far-right politician Andrej Sisko said his group - seen conducting training drills - would "secure public peace and order" if needed.

President Pahor said there was no place for such a group in the country.

Police are investigating the group, which posed with assault rifles but denies being a paramilitary unit.

Videos posted on Facebook show some 70 masked people allegedly taking a "solemn oath".

The group is led by an unmasked Mr Sisko, who once served prison time for attempted murder.

He won 2.2% of the vote last year when he ran for president of the small EU state, which was once part of the former Yugoslavia.

He lost out to Mr Pahor, whose cabinet said in a statement: "President Pahor stresses that Slovenia is a safe country in which no unauthorised person needs or is allowed to... illegally care for the security of the country and its borders."

The outgoing Slovene Prime Minister Miro Cerar said the formation of the unit was "absolutely unacceptable" and that it "needlessly stirs up fear and spreads hatred".

Allow Facebook content?

This article contains content provided by Facebook. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Facebook cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Mr Sisko denied the group - called the Stajerska Guard after a north-eastern region - was doing anything illegal, telling Reuters news agency it was a voluntary defence force consisting of "several hundred people".

However, he conceded the weapons they carried had not been registered with authorities.

Andrej Sisko's United Slovenia Movement party gained 0.6% of the vote in June's election

'Public indifferent to Sisko'

By Guy Delauney, BBC correspondent

Andrej Sisko is far out on the fringe of Slovenian politics.

He styles himself as a patriot, fighting to preserve the Slovenian people and the country's distinct identity - in the face of much larger neighbours populated by different ethnic groups.

On occasion, this ideological fight has spilled over into real violence.

Mr Sisko served a two-year jail sentence after planting a car bomb. He also has a long track record of forming or joining militia groups.

He will welcome the publicity gained by his latest stunt. But the public remain indifferent: his United Slovenia Movement gained just 0.6% of the vote in June's general election.

National security expert Iztok Prezelj told local media the group had all the markings of a militia: "They have a flag and uniform, but also from photographs, it's obvious that they have some common emblem on the T-shirts."

The University of Ljubljana vice-dean added: "Currently, Slovenia is not at risk of security, so I do not see the need to organise any armed formations, in addition to the army and the police."

"The police have not visited me so far but I expect their visit," Mr Sisko said. "We are doing nothing wrong and we would be even interested in co-operating with the police."

However he told media that his unit, which was allegedly formed 14 months ago, "would not watch quietly" if police attempted to disarm them.

In fact, the police might be disarmed instead, Mr Sisko told Slovene daily Delo on Tuesday.

His party, the anti-immigrant far-right United Slovenia Movement, has no connection to the militia, he said.

Slovenia is due to confirm a new minority government of five centre-left parties in the parliament next week.

An anti-immigrant stand helped the centre-right Slovenian Democratic Party to win most votes at the June election but the party lacked coalition partners to form a government.

According to the Slovene media, the new government has already attracted criticism from the opposition for what are seen as its "radically leftist moves", and there are concerns that it will take too lax an approach to the issue of migration and the protection of national interests.

Anti-migrant sentiment has increased in Slovenia since almost half a million migrants crossed the country on their way to richer EU states in 2015 and 2016.

The number of requests for asylum in Slovenia has risen significantly from 277 in the whole of 2015 to 1,717 so far this year.

However, only 77 people have been granted an asylum in 2018, versus 152 in the whole of 2017, interior ministry data showed.

- Published3 June 2018

- Published28 June 2023