Why is IVF so popular in Denmark?

- Published

Pia Crone Christensen and daughter Sara, born from IVF and donor sperm

Despite previous attempts to limit access to treatment, Denmark now has the biggest proportion of babies born through assisted reproductive technology (ART) in the world.

Visit any park in Denmark and the chances are many of the children playing there were born using IVF or donor sperm. Denmark leads the world in the use of ART to build families - an estimated 10% of all births involve such techniques.

Everyone in Denmark knows someone who has gone through IVF and talking about it is no taboo - chats at the schools gates or even church frequently revolve around the origins of people's children.

Pia Crone Cristensen - mother to two-year-old Sara, thanks to IVF and donor sperm - is one of a growing number of single women making use of Denmark's liberal IVF rules. After failing to find a suitable partner to father her children, she decided to go it alone, when she was 39.

"I think it's great that women finally have the upper hand - we can choose to become pregnant if we want to. I think that the problem is not necessarily that women don't want the men but that the men don't want to commit to having children. It's either doing it solo or not having children at all.

"I was lucky to become pregnant in the first round of the IVF. I remember giving birth and was just so grateful. I sat in the chapel of the hospital crying. I just needed to be grateful somewhere.

"People are very open about it. I went to a baptism not too long ago and I guess because people know that I got Sara the way I did, they were telling me, 'Oh, we're trying for another baby. You know, we got this one with IVF and we're trying again.' You don't necessarily have to be very close to have that conversation."

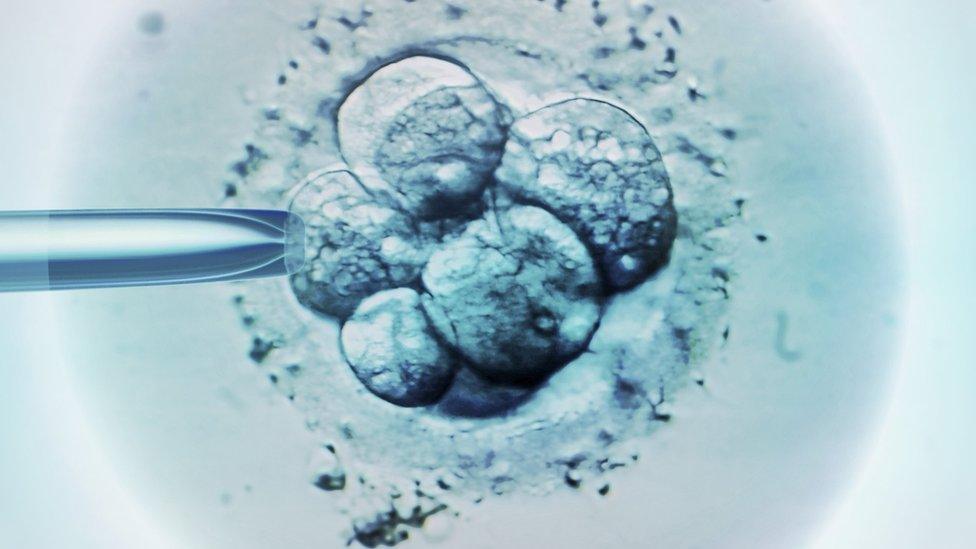

In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF)

An egg is removed from the woman's ovaries and fertilised with sperm in a laboratory

The fertilised egg is then returned to the woman's womb to develop

IVF worked for the first time on 10 November 1977. On 25 July 1978, the world's first IVF baby, Louise Brown, was born

On average, IVF fails 70% of the time

The highest success rates are for women under 35, one-third of treatment cycles are successful

On average, it takes almost four-and-a-half years to conceive with IVF

Source: Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority/Fertility Network UK

The birth of Troels Renard Østbjerg in 1983 marked the start of Denmark's journey from just another developed country trying to make the fledgling technology work better to becoming the world record holder for ART births.

Today, only Israel challenges Denmark's IVF crown. It has far more cycles of IVF per million inhabitants - about 5,000 compared with Denmark's 2,700. But a much lower natural birth rate and higher IVF success rate means that Denmark wins on the proportion of babies in the population born thanks to reproductive technology.

Prof Claus Yding Anderson, at Copenhagen's University Hospital, was part of the team that bought IVF to Denmark. He attributes its popularity to generous state funding.

"It reflects that we have a public health care system that is paying. Anything which is treatment in Denmark is free, full stop.

Prof Claus Yding Anderson says IVF's popularity is largely due to Denmark's generous state provision

"We had this national discussion that the public health care system takes care of a nose which is bending to one side, or ears which [stick out], where basically you are not sick, so it was pretty straightforward to say, 'Well of course we need to include IVF.'

"Money doesn't grow on trees in Denmark but this is the Scandinavian system. Everybody is willing to pay a lot in tax but everybody is benefiting."

Find out more:

The Changing Face of Procreation was broadcast on the BBC World Service.

Click here to listen to the first part and here to listen to the second part. Or you can download the programmes via the BBC World Service Documentary podcast.

Dr Sebastian Mohr, from Sweden's Karlstad University, has followed the growth of reproductive technology,

"Denmark has reproduced itself as a certain kind of nation. The state financing it, the people using it, the medical professionals lobbying around it - reproduction has become a national project rather than just a project of the individual."

But he points out that along with generous state funding comes state control of access to IVF.

Detailed criteria are not published but only people deemed to be "fit parents" are approved. Women over 40 don't get state-funded treatment and those over 45 are also barred from accessing IVF privately.

Dr Mohr argues that the decision-making process should be more public. He is investigating records of IVF funding decisions and says he has seen evidence that people who are considered "too disabled" are denied state funding.

It didn't used to be this way. During the 1980s and 1990s, IVF and other reproductive technologies went largely unregulated in Denmark. Doctors decided who should get treatment, initially only offering heterosexual couples the chance to conceive.

However, private clinics were free to treat anyone, and anything was possible: surrogacy (now banned in Denmark), IVF using donor sperm, and access for lesbian women.

IVF became controversial. Radical feminists complained that it meant medically trained men were commodifying women's bodies, while social conservatives also objected to the technology.

But in 1997 the government passed the Act on Artificial Fertilisation. Single women and lesbians - who for years had been able to pay for IVF and donor insemination - were now barred.

Denmark is now home to the world's largest sperm bank, run by Cryos International

The new legislation sparked a fight for equality of access - but in the meantime, others spotted a loophole.

The law only banned doctors from carrying out the procedures, which led to a boom in specialist midwife-led clinics.

One such facility, the StorkKlinic, named after its midwife founder Nina Stork, became a big draw for single and lesbian women from across Europe wanting to start families. Just 5% of its clients today are Danish.

"The law opened up the possibility for entrepreneurs to establish a clinic where people could use these services even though the actual intention of the law was to exclude people," says Dr Mohr. "These clinics showed that it could be done responsibly."

In 2007 the current ART law was passed, granting access to state-funded IVF regardless of a woman's marital status or sexuality.

It marks Denmark out as one of the most permissive countries in the world in terms of who can get IVF and the decades of debate have moulded Danish society into one in which most people support the government's position.

The fertility industry is now one of Denmark's most successful exports and the country is is also home to the world's biggest sperm bank, Cryos International, which deals with customers around the world.

However, as the number of Danish women accessing IVF and insemination to have children has grown, so has the backlash.

Rasmus Ulstrup Larsen says that last year he was the most hated man in Copenhagen.

Rasmus Ulstrup Larsen wrote an article complaining about the rise of "solo-mums" in Denmark

A 28-year-old high school economics teacher, he has become the unlikely figurehead for a section of Danish society that remains deeply unsettled by the social changes brought about by Denmark's liberal assisted reproduction laws.

In particular, some worry about the growing number of single women, such as Pia Crone Christensen, having children.

In 2017, Mr Larsen gained notoriety with a newspaper article that called solo mums "a horrible modern phenomenon" (in Danish), external.

"This increase of solo mums is a result of a sociological evolution. We see here in Denmark an individualistic ethics of self-realisation. It's the same as the high divorce rate. It's the same kind of culture that cultivates both things.

"We need more common goals, a more shared way of living instead of this individualistic way of perceiving life."

But he accepts he's fighting a losing battle.

Increasing numbers of single Danish women are having babies with donor sperm. The proportion of babies born in Denmark thanks to reproductive technology is steadily rising.

And as long as Denmark's fertility rate stays low, the government is likely to keep supporting treatment that helps the population to grow.

- Published23 August 2018

- Published12 August 2018

- Published4 November 2017

- Published23 October 2017

- Published20 July 2018