Tintin and the vanishing murals: Brussels races to save art

- Published

The young Hergé depicted boy scouts in this Greek-style mural

He's one of the best-known artists of the 20th Century but, before The Adventures of Tintin, the Belgian artist Hergé created art of a different kind - murals at the Brussels school where he once studied.

In the early 1920s Hergé, then a 15-year-old Georges Remi, was a scout and student at Institut St Boniface, in the Ixelles area of Brussels.

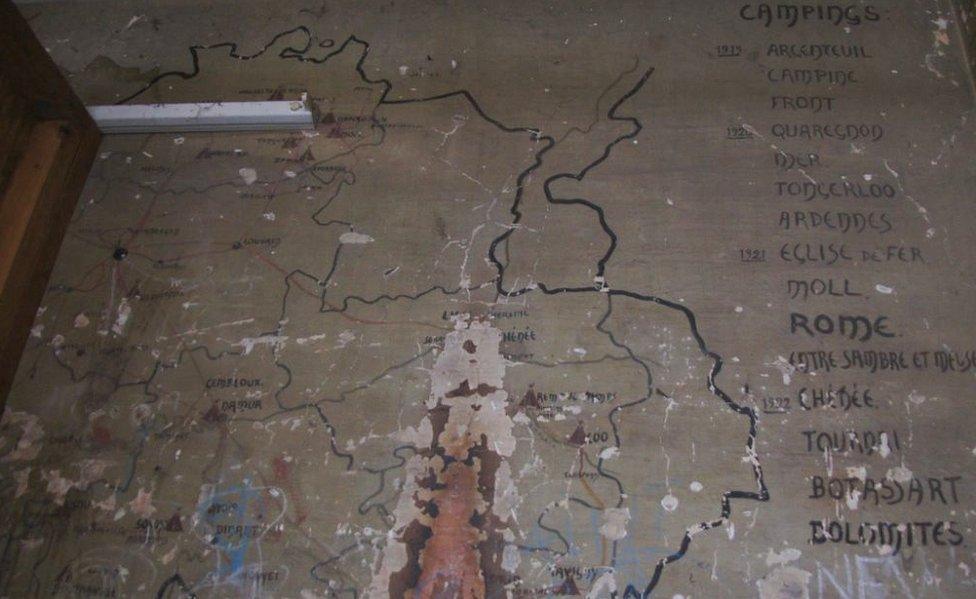

He adorned the walls of the old scout HQ with lovingly rendered art showing scouts and Native American Indians, as well as a map of Belgium.

But now the small garage is in disuse, the walls are in a poor state and many of his drawings have crumbled away.

Hergé recorded the scouts' many trips on this map

Tintin's popularity is enduring. The intrepid reporter is a symbol of Belgian culture and helped to inspire an entire art form in the early days of the comic book.

Although Tintin was created in the 1920s, it was during his 1940s run in the Belgian newspaper Le Soir that he really took off.

But Le Soir's very existence hinged on its support for the Nazi regime. Accusations of being a Nazi sympathiser have dogged Hergé ever since.

Read more about Tintin:

Brussels has long celebrated its fictional native son

Yet Tintin is still adored the world over. He even got the Hollywood treatment, with a in 2011 film by Steven Spielberg.

For that reason, according to historian and archivist Thierry Scaillet from the Catholic University of Louvain, it's essential to preserve this "first graphical trace of Hergé".

"It's the only place we know of that still exists where Hergé decorated the walls," he says.

Another Hergé mural shows medieval knights

"There were other frescoes by him in the same school but those walls disappeared after World War Two.

"It's the oldest work by Hergé that we know of," Mr Scaillet told the BBC.

He sees a clear link between those formative years as a scout and the exploits Hergé would later create for Tintin and his little white dog Snowy.

Scouts like the young Georges Remi would often travel across Europe for up to three weeks, and those trips would cement in the young Hergé a "taste for adventure and exploration".

Hence the boyish drawings of Native American Indians and the exotic adventures of Tintin.

The school in Ixelles needs to approve any work

Local geographer and councillor Yves Rouyet is leading the charge to preserve and display these drawings - but it's not an easy process.

"No-one has done an estimation of what it would cost to restore them yet," he says, frustrated by a lack of movement.

Much depends on events outside of Mr Rouyet's control. Local elections, which affect funding decisions in the Ixelles commune, take place in October. The school, which has for the first time begun to display these drawings, needs to agree to any changes on its own premises.

But Mr Rouyet insists on the need to safeguard and display these drawings to the public and experts.

"It's important to preserve them. It's important for the history of humanity, for the history of comic books."