Trump INF: Back to a nuclear arms race?

- Published

Mikhail Gorbachev (left) and Ronald Reagan signed the treaty in 1987

The US decision to walk away from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty has significant consequences for the future of arms control, for perceptions of the US and its approach to the world - but also for strategic competition between both the US and Russia on one hand, and Washington and Beijing on the other.

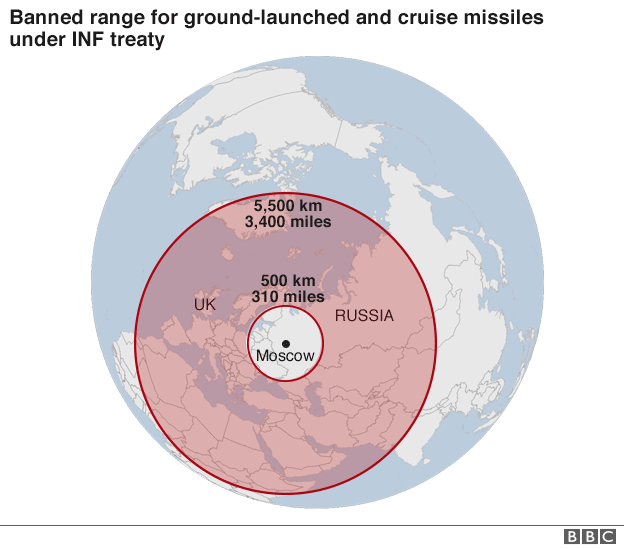

The INF treaty is significant in that it banned a whole category of nuclear missiles: ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges of between 500-5,500km (300-3,400 miles). These were seen as highly destabilising, so the deal marked a major step forward in arms control. The treaty was an important element in a whole network of disarmament and arms reduction treaties that sought to manage and reduce tensions during the Cold War.

Today relations between Russia and the West are again under strain but the whole edifice of arms control is slowly crumbling. A treaty intended to limit the build-up of conventional forces in Europe is largely ignored. Russia, through its support for the Syrian regime, has weakened the prohibition on the use of chemical weapons.

There are even doubts about the fate of the 2011 new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (Start) between Washington and Moscow which limits the number of deployed, long-range and strategic nuclear systems. The treaty needs to be extended by February 2021 or it will expire - and if it does there will be no legally binding limits on the world's two largest strategic arsenals for the first time since 1972.

The treaty is the latest bone of contention between the US and Russia

Advances in technology threaten to create whole new categories of weapons, from cyber to genetic, and advocates of arms control warn that this is no time to be abandoning existing disarmament agreements, insisting they should actually be built upon and extended into new areas.

Destroying the INF agreement opens the way for Russia to deploy many more of the missiles in question - increasing both the threat to Nato countries but also, in all likelihood, the differences between many of them and Washington in strategy direction.

Dismay in Europe

Russia may indeed be in breach of the treaty if the US is to be believed but it is the Trump Administration that will be blamed for tearing it up. This matters: President Trump already has a track record of abandoning deals entered into by his predecessors - from the Iran nuclear agreement to treaties on climate change and trade.

Many fear that Mr Trump is gradually destroying the liberal international order that the US was largely responsible for constructing post-WW2. Certainly this is not Mr Trump's doing alone. The contemporary world disorder is marked by a range of states - large and relatively small, from Russia to China, to Turkey, to Saudi Arabia - all who have strong authoritarian leaders determined to do whatever they think they must to further their national interests.

Critics of Mr Trump say that an America that no longer stewards the global order facilitates such trends. Mr Trump may argue that he simply wants a better INF deal, in the same way he insists he wants a better and more restrictive nuclear agreement with Iran but what are the chances of him achieving either of these goals?

Many of Washington's closest allies will be dismayed at the Trump administration's decision on INF, even while they share Washington's assessment of Russia's behaviour. There will be little enthusiasm in Western Europe for the deployment of new ground-launched US nuclear systems.

Dangerous new era

The collapse of the INF agreement more generally sets a new and more dangerous context for strategic rivalry between the US and Russia.

Despite its nuclear arsenal, Russia remains a relatively weak player compared to the US. However it remains determined to use what limited leverage it has as a disruptive force. Russia's cyber and information warfare operations are well documented - intruding into election campaigns and the political life of several nations - quite apart from its military engagement in Ukraine and Syria.

The Trump administration - largely because of Mr Trump's own curious attitude to his Russian counterpart - has sometimes appeared ambivalent towards Russia. But overall, irrespective of Mr Trump's personal Twitter storms, there is a hardening line.

We are entering a new era of strategic competition. It is not necessarily a Cold War Mark II because Russian power is in no way comparable to that of the Soviet Union. But it is a dangerous period - especially if many of the agreements that provided the "rules of the road" are to be abandoned.

The Pacific dimension

One suggested reason for the Pentagon's willingness to overthrow the INF agreement is Washington's growing strategic rivalry with China - the military competition that is going to shape the coming decades.

As economic power shifts eastward, the US is eager, if not to contain China, then to build up its own forces to better counter their rapidly modernising military capabilities. The US wants to maintain access to international waters in the face of Chinese encroachments, as well as to reassure its allies in the region that it remains a Pacific power to be reckoned with.

China was not a party to the INF treaty and has not been bound by its limits. In 2015, for example, it deployed the Dong Feng-26 system - a ballistic missile with a range of 3,000-4,000km - far enough to enable it to strike most US bases in the Pacific.

But what remains unclear is the value there is in the US developing and deploying similar systems if the INF treaty is abandoned. Where would it put them, for example? Many of its allies might be reluctant to host such systems and air- and sea-launched alternatives might prove far more useful.

This point is as valid in Europe as it is in the Asia-Pacific region. The INF treaty bans ground-launched systems but says nothing about air- and sea-launched equivalents. If the US really wants to do something about the INF treaty it could continue to try to press the Russians back into compliance while developing new weapons systems of its own that would not breach the agreement - but that is not Mr Trump's style.

With Russian spokesmen insisting that their response to a US withdrawal would be "to act to restore the nuclear defence balance" there's a danger of a renewed nuclear arms race.

- Published15 February 2017

- Published18 January 2017

- Published29 July 2014