Dutch language besieged by English at university

- Published

At the highest honours level at Utrecht barely any courses are taught in Dutch

Students shake off their jackets and scarves as the lecturer opens up a power point presentation on "start-up innovations" and prepares to give his talk, which is entirely in English.

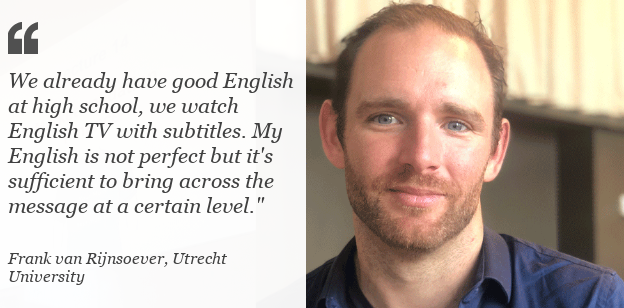

The language is the university's choice, Frank van Rijnsoever of Utrecht University tells me.

So extensive is the spread of English in Dutch universities, a group of lecturers has predicted a looming "linguicide" and demanded the government in The Hague impose a moratorium banning universities from creating any additional English language courses until an official impact analysis has been conducted.

Sixty per cent of masters programmes offered at Utrecht University are in English. At the highest honours level, virtually no courses are taught in Dutch.

The biggest challenge is for Dutch students at Utrecht to do all their studies in English

"I don't mind. Most of the literature is in English," says Mr Van Rijnsoever.

"So for me as a teacher it's not that much of a problem because we also do research in English. For the students, you see they have to cross a certain barrier to properly express themselves."

The Netherlands has one of the world's highest levels of English proficiency, external among non-native speaking countries, second only to Sweden, according to the latest EF English Proficiency Index.

"It's something I picked up over the years, mainly while doing my PhD in academic English." the lecturer explains.

For Oskar van Megen, who graduated with a degree in sustainable development, taking an internationally orientated Master's in English made sense as the subject was broader than in the Netherlands.

"It did give me a bit of a disadvantage. It took me way, way more time to understand and focus on the lecturers, and to understand the articles and write my own articles."

Oskar van Megen is pleased his masters degree was in English but finding work in the Netherlands has proved difficult

However, while he feels qualified for an international career, he has since struggled to find work in the Netherlands.

'Use it or lose it'

Utrecht is not alone.

Some Dutch universities have completely erased the Dutch language from the campus. In Eindhoven, even the sandwiches in the canteens are sold as cheese rather than with the Dutch word "kaas".

And not everyone is happy with such a creeping Anglicisation at university.

"It's our identity, Dutch," complains Annette de Groot, professor of linguistics at the University of Amsterdam.

"What happens to the identity of a people of a country where the native language is no longer the main language of higher education?

"The Dutch aren't as good at English as they think they are. You shouldn't use a weaker language in education."

Prof Annette de Groot fears a detrimental effect on the Dutch language

"If you use English in higher education, Dutch will eventually get worse. It's use it or lose it. Dutch will deteriorate and the vitality of the language will disappear. It's called imbalanced bilingualism. You add a bit of English and you lose a bit of Dutch."

While English can ease students into the global market, others feel its prevalence is excluding them from their homeland.

And a political debate here is intensifying, as more UK citizens move here because their companies wish to remain in the EU post-Brexit,

It is time, says Prof De Groot, for an honest debate.

"We're shifting to a more and more Anglo-Saxon view of the world. Universities want diversity, different perspectives. What you get is exactly the opposite. The Anglicisation means you end up with a much more homogeneous world."

The irony for her is that Dutch universities are merely competing for students in a bid to survive.

Utrecht's campus offers more than 80 Master's programmes in English as well as honours programmes

Utrecht University Rector Henk Kummeling argues that moving towards English has been an organic process but accepts that when competing internationally, it makes sense to use a world language.

"It's not that we are advertising for international students," he tells me from his office overlooking a bicycle-strewn campus.

"Dutch culture will stay for centuries. When we talk as Dutchmen amongst ourselves, we speak Dutch."

Oskar agrees, saying he enjoyed forging friendships with students from the UK, Ireland and Italy.

"Personally I don't have any troubles with not speaking Dutch or with Dutch culture, which is maybe disappearing a bit."

But he says there has to be a limit, and suggests Groningen University in the north has taken in too many international students. "There are so many they have to set up tents just so the students can have a roof over their heads," he complains.

The danger for him is that universities are trying to increase their international profile while pushing for income from foreign students, while making compromises in other ways.

- Published3 December 2015