'Not Disneyland': Dutch hit back at 'over-tourism'

- Published

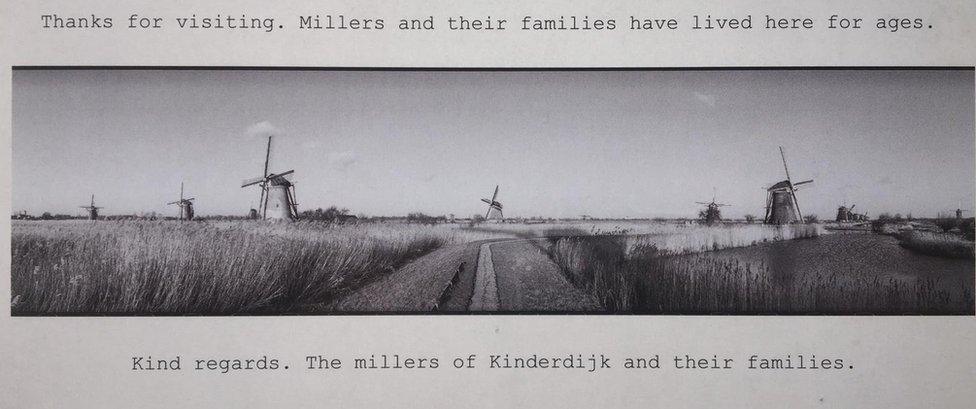

Kinderdijk's 19 windmills attract tourists all year round

Two tourist coaches career along the narrow winding road past a human-sized yellow clog. Bus after bus queues to drop off its eager passengers, creating tailbacks down the rolling dykes as far as the eye can see.

Nineteen windmills occupy the village of Kinderdijk near Rotterdam. A quintessential structure of Dutch iconography, this is one of the most photographed destinations in the Netherlands.

Filing out into the misty rain, the tourists pop open their scarlet umbrellas expectantly and a tour guide brandishes a red marker sign in the drizzle, explaining the significance of this unique Unesco-recognised site, external.

Constituting a masterpiece in water management, the mills once drained the water from the land, preventing flooding since around 1740.

But this is not a museum, the mills are full of life.

Even when rain pours the tourists keep coming

And some residents who live in the mills have had enough. They have created postcards inviting the tourists to consider the impact of their visits.

Trampling through the tulips

"I have many, many bad experiences with the tourists," says Johan Velthuizen, a 56-year-old robot programmer. He's lived in Kinderdijk his whole life and runs the "liveability" local action group that's been petitioning the mayor to better manage the mass tourism.

"They run through my garden with their whole families. We're sitting drinking tea in the sunshine, then we look up and there's a Chinese family trampling through my flowers.

"To start with it was just tourists from the US or the UK, now it's China and Japan. They have so many millions of people, they all want to come to have their photo with a windmill."

Over-tourism and what to do with it

Venetians are trying to find solutions to stop the exodus from their city

Buses block roads, cars commandeer designated disabled parking spots and tourists with no experience of cycling are encouraged to hop on the saddle to experience the fully immersive Dutch experience.

Videos posted by Johan's team demonstrate some of the issues created by "overtourism", external in what used to be a quaint Dutch village now suffering from its very nature. A decade ago, this place was barely known beyond the dykes.

The council has sought to minimise disruption by banning coaches and camper vans from the centre of Kinderdijk, building new parking facilities on the outskirts of the village and conducting intensive checks on cars that have resulted in an almost doubling of fines between 2017 and 2018.

Miller Peter Paul Klapwijk says as many as 800 cruise ships dock near Kinderdijk every year

"I produce some coffee mugs and coasters for a hobby," Mr Velthuizen complains. "But the tourists are just coming to take photos not to spend anything; they get all their food on the cruise ships."

For all his frustration, he disagrees with a recent initiative by local millers to hand out postcards to tourists that suggest their presence is part of the problem. The postcards convey a a simple message:

"We've lived here for centuries. We get 600,000 tourists a year and there are 60 of us. Ratio 10,000:1 #overtourism"

Although intended to be posted to friends to ward off other potential visitors, the postcards are perhaps more likely they will be kept as souvenirs.

Local miller and Instagram enthusiast Peter Paul Klapwijk, external makes the point: "It's a world heritage site, not Disneyland. And it should be treated as such."

Many residents complain they fail to see any benefit from the large number of tourists

And yet, it costs €20,000 (£17,000; $23,000) a year to keep a mill turning so the tourism income that comes from the Kinderdijk heritage foundation that runs the site is a vital source of funding.

"We are part of the heritage," says Mr Klapwijk. "We don't hate tourists but the heritage foundation treats us like the goose that laid the golden egg."

'We just need rules'

Entry tickets cost €8 per adult and hundreds of cruise ships dock near by every year, providing an estimated €4m for the foundation.

Most of the money is reinvested into maintaining the site but residents complain they are frozen out of council consultations and do not see any benefit from accommodating the tide of tourists.

A decade ago Kinderdijk was barely known but now it is a key stop on the tourist trail

They've launched numerous court cases to try to protect their property and prevent the attraction from being expanded.

"You can't stop it. We just need rules. The tourists used to just come in the summer and stop in October, now it's all year," Johan Velthuizen complains.

The solution for miller Peter Paul Klapwijk is to create a connection with visitors to give them a greater understanding of residents' lives.

Now when he spots a tourist training a long lens on his family home, he invites them over for a chat.

- Published16 April 2018