Akli Tadjer: French writer meets students in school race row

- Published

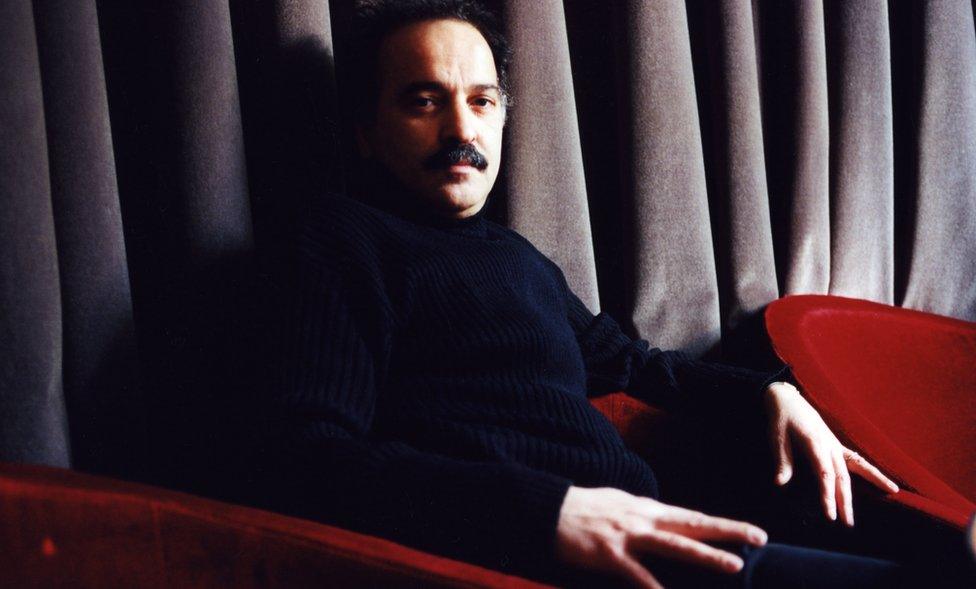

Akli Tadjer met 25 pupils from the school in Péronne (file picture)

A novelist whose book was rejected by French teenagers because of its Algerian theme has visited their school in the Somme region to meet them.

Akli Tadjer, a French writer with Algerian roots, said afterwards that it had been a learning experience for both the students and himself.

He had been invited by their teacher who had complained about some of her pupils' "racist remarks".

Algeria achieved independence from France in 1962 after a bloody war.

Bitterness remains on both sides, with refugees and their descendants having had difficulty returning to Algeria.

What had happened at the school?

In September, a teacher at the Lycée Pierre Mendès-France in Péronne asked her class to read extracts from Tadjer's novel Le porteur de cartable (The Satchel-Carrier).

While not on the school syllabus, the 2002 novel was chosen by the teacher as part of a "reading journey", French reports say.

It tells the story of the war in Algeria from the perspective of two children, one the son of an independence fighter, the other the son of a French colonist forced to flee Algeria.

Some students, the teacher later told the writer in an email, refused to read the extracts.

She said they complained the author was not French, the story had nothing to with France, the book contained words in Arabic and the hero's name was Messaoud (a popular boy's name in the Arab world).

In reality, the author is French and Algeria's colonial history is bound up with France, as much of it was part of France until 1962.

"The remarks were truly racist,", external the teacher wrote in her message, posted by Tadjer on Facebook.

The school took action against the seven students involved, giving three serious punishments, external, French radio reports. A pupil who refused to pronounce the name Messaoud was sent before a disciplinary committee.

How did the visit go?

No media were admitted to Friday's meeting, which involved 25 students, all of them boys, and lasted an hour, but both the writer and a school official spoke afterwards.

Tadjer told the students the story of his life, recalling his illiterate parents and the literature which had inspired him, external, local news site Le courrier picard reports.

Tadjer, who was born in Paris in 1954, has been writing prize-winning novels and scripts since the mid-1980s.

When he asked who among them were not racist, all but two raised their hands. When asked why they had not raised their hands, the two then said they were "not racist and that it was political".

The writer said he had been astonished to hear that nobody in the class wrote anything except text messages but then one student had confided that he had written a book and everyone applauded.

"The pupils learnt things about me and I also learnt from them," he said.

School inspector Jérôme Dambla said the meeting had been a "healing moment" and he hoped that some "seeds of doubt" had been planted that might bear fruit in "five to 10 years' time".

The class teacher, who was also at Friday's meeting, was said by the school to be "relieved and happy" afterwards.

Why is Algeria still such a thorny subject?

The war of independence which raged from 1954 to 1962 saw atrocities committed by both sides and ended with the exodus of Algeria's European population, known as Pieds Noirs, as well as those indigenous Algerians who had sided with France, known as Harkis.

Since the 1960s, other Algerians have immigrated to France and they now make up one of the country's biggest ethnic communities.

Many live on the margins of society in run-down housing estates, known for social problems, and say they face racist discrimination in the jobs market.

Before Friday's meeting, Tadjer had pointed out that young Arab soldiers, many of them named Messaoud, had died on the battlefields of World War One in the Somme region.

"To not pronounce the name Messaoud is like killing the young soldiers who died for them all over again," he said.

France has long campaigned to stamp out racism, with the government announcing this year a new drive to rid social media of hate speech after a rise in incidents targeting Jews and Muslims.

- Published13 September 2018