Anti-Semitism pervades European life, says EU report

- Published

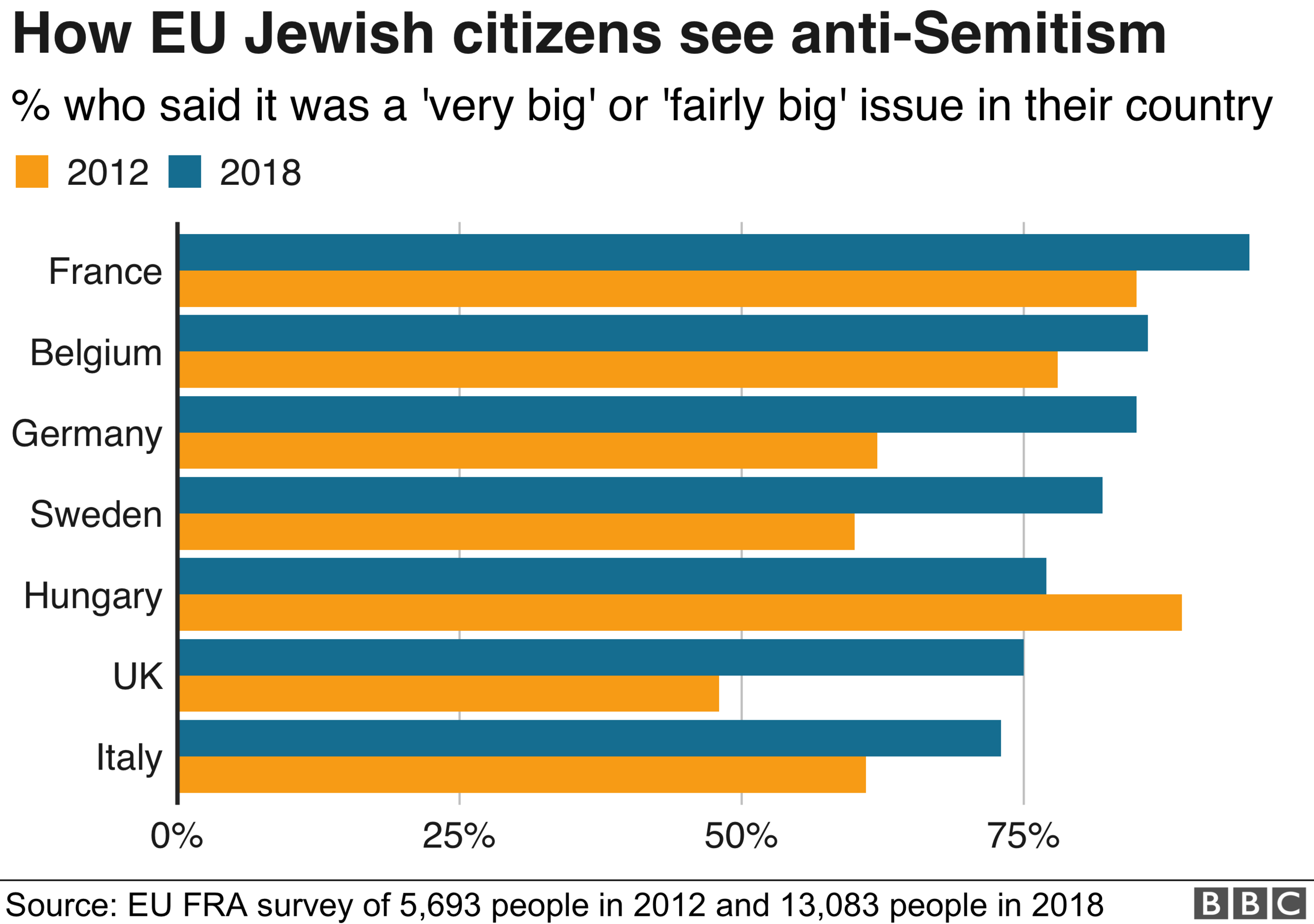

A startling 95% of French Jews see anti-Semitism as either a fairly or very big problem

Anti-Semitism is getting worse and Jews are increasingly worried about the risk of harassment, according to a major survey of 12 EU countries.

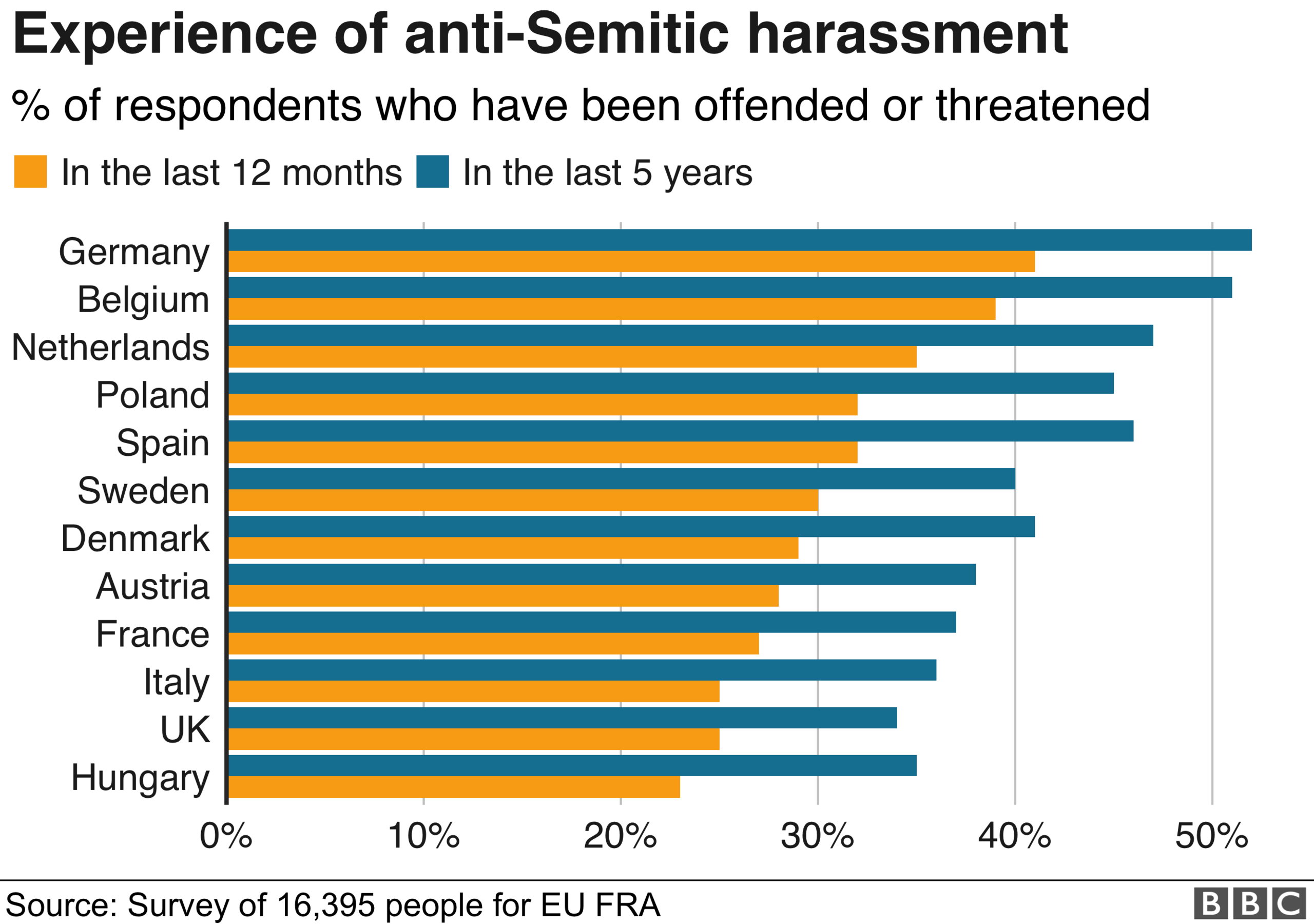

Hundreds of Jews questioned by the EU's Fundamental Rights Agency said they had experienced a physical, anti-Semitic attack in the past year, while 28% said they had been harassed.

France is identified as having the biggest problem with anti-Semitism.

Germany, the UK, Belgium, Sweden and the Netherlands also saw incidents.

On the day the report was released, the Italian police said they were investigating the theft of 20 memorial plaques commemorating the Holocaust.

The small brass plaques - dedicated to members of a Jewish family, De Consiglio - were dug out from Rome's pavements during the night.

What are the main findings?

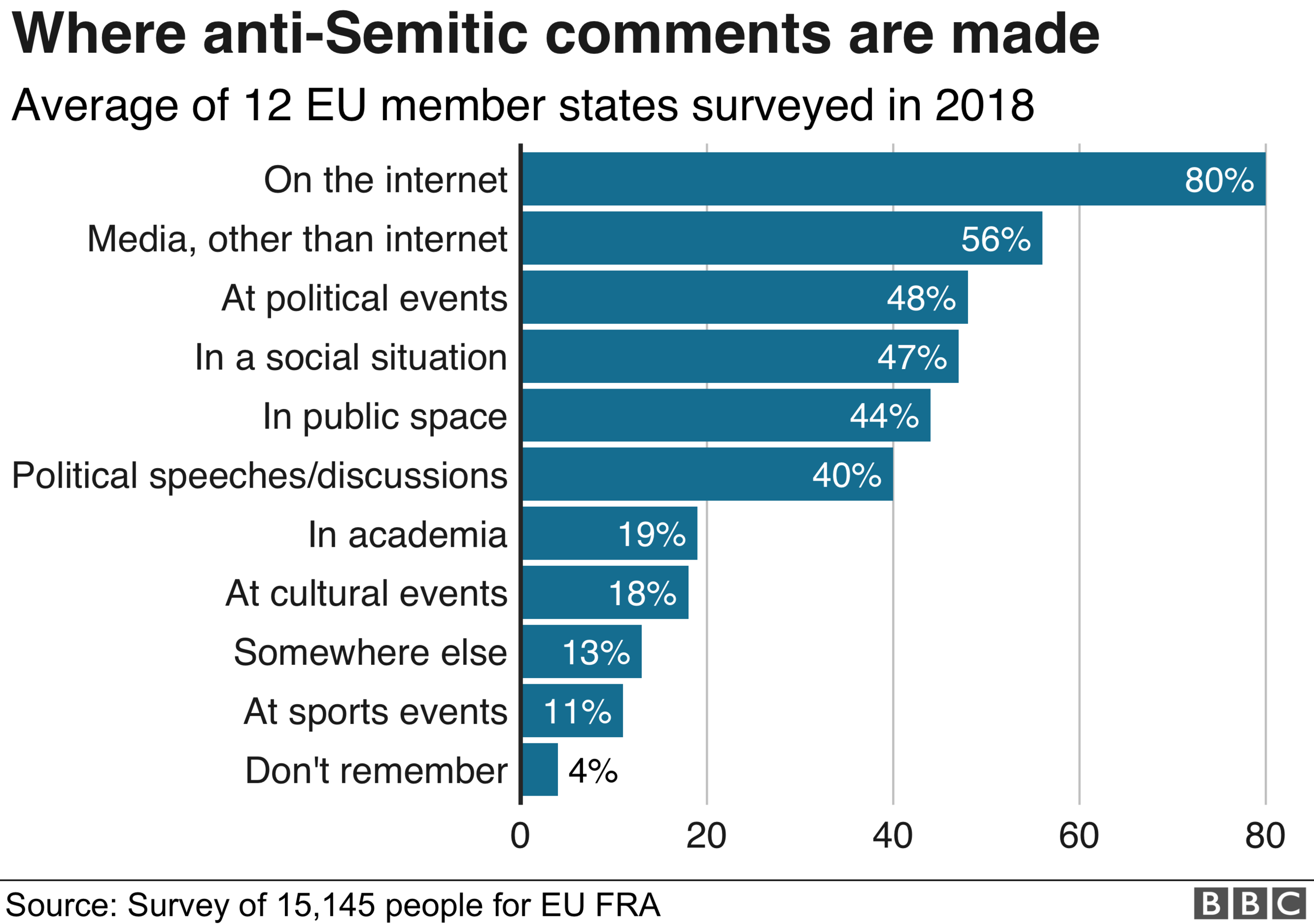

The Vienna-based FRA paints a picture of synagogues and Jewish schools requiring security protection; of "vicious commentary" on the internet, in media and in politics; and of discrimination at school and work.

The report comes weeks after a gunman murdered 11 people at a synagogue in the US city of Pittsburgh.

Six years after its initial report, the FRA has surveyed Jews in the 12 EU states where most Jews live, external.

The report says anti-Semitic abuse has become so common that most victims do not bother reporting the incidents. Among the findings:

89% of the 16,395 Jews surveyed considered anti-Semitism online a problem in their country

28% experienced some form of harassment for being Jewish in the past 12 months; 2% were physically attacked

47% worry about anti-Semitic verbal insult or harassment and 40% about physical attack in the next 12 months

34% have avoided Jewish events at least occasionally because of safety fears

38% have considered emigrating in the past five years over safety fears

Where is anti-Semitism most significant?

A startling 95% of French Jews see anti-Semitism as either a fairly or very big problem.

France has been subject to a string of jihadist attacks, including the killing of hostages at a Jewish supermarket in Paris.

This year alone 85-year-old Mireille Knoll, who escaped the Holocaust, was murdered in her Paris flat and an eight-year-old boy wearing a kippah (skullcap) was attacked in the street by teenagers.

There was an outcry across France when Mireille Knoll was murdered in her Paris home

Prime Minister Edouard Philippe has spoken of a 69% increase in anti-Semitic incidents in the country, which has Europe's biggest Jewish population of around half a million.

He said a national network of investigators would be created to fight hate crime, and a school taskforce would be sent to help teachers tackle anti-Semitism in the classroom.

Over 80% of those surveyed saw anti-Semitism as a serious problem in Germany, Belgium, Poland and Sweden.

Last month, Chancellor Angela Merkel said Germans had become almost accustomed to Jewish institutions requiring police guards or special protection.

Sweden, meanwhile, has seen one of the sharpest increases in perceptions of anti-Semitism in the past six years, along with the UK and Germany.

Why has Sweden seen such a steep rise?

"I think a lot of Jews in Sweden are scared," says Isak Reichel, secretary general of the Stockholm community.

Last year a neo-Nazi hate campaign forced a Jewish community association to close its doors in the northern town of Umea.

Then in December three men of Middle Eastern origin threw petrol bombs at a synagogue in Gothenburg while young people were holding a party. That attack took place after US President Donald Trump announced he was recognising Jerusalem as Israel's capital.

Sweden's Jewish population is only 20,000, and most are particularly careful not to stand out.

"Most Jews in Sweden don't show publicly they are Jews," says Mr Reichel. "They don't walk around with a kippah. If they have a Star of David around their neck, they hide it. Children in school don't say they are Jewish," he told the BBC.

What's happening in the UK?

Most anti-Semitic incidents in the UK involve abusive behaviour and the numbers last year hit a record, according to the Community Security Trust, a charity that works with the police to protect Jews.

For months in the summer anti-Semitism was at the centre of political discourse, with allegations surrounding the opposition Labour Party and its leader, Jeremy Corbyn.

The party argued over the role of Israel in the definition of anti-Semitism adopted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), external. Labour finally agreed to it in September, but added a statement on protecting free speech.

Weeks later Jewish Labour MP Luciana Berger needed police protection during the party's annual conference.

In March, protesters gathered outside Parliament calling for Labour to do more to fight anti-Semitism

The Labour row has had repercussions for Jewish students too, says the head of the Union of Jewish students, Hannah Rose.

"There have been two main effects," she told the BBC. "One is normalisation of anti-Semitic rhetoric on the left - and it's become less challenged when it does occur; secondly, non-Jewish students believe they know anti-Semitism more than Jews themselves.

"People don't want to seem to educate themselves on how you can criticise Israel without being anti-Semitic."

She left the Labour party in September.

What does the EU recommend?

Last week the EU Council agreed a statement, external calling on member states that had not yet done so to endorse the IHRA's non-legally binding working definition of anti-Semitism as a useful guidance tool in education and training

The rights agency's report also urges EU countries to "systematically co-operate" with Jewish communities to protect Jewish sites

The report says victims should be urged and helped to report incidents of anti-Semitic discrimination.

- Published9 November 2018

- Published27 November 2018

- Published5 July 2018