Migrant crisis: Illegal entries to EU at lowest level in five years

- Published

The route from North Africa to Spain is now Europe's most active

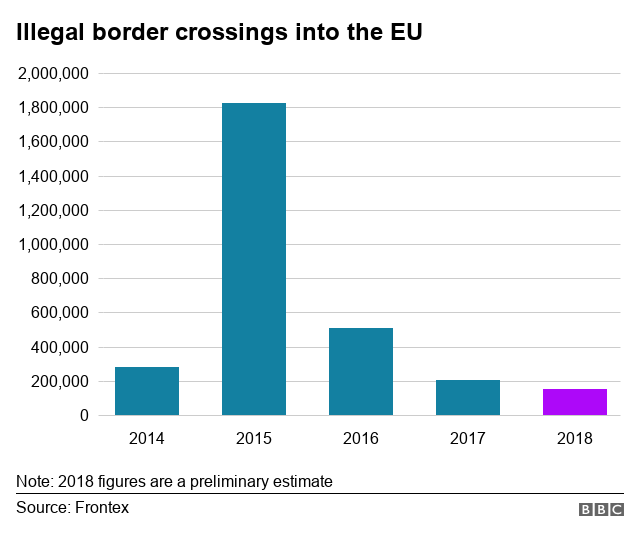

The number of people caught trying to enter the EU illegally has fallen to its lowest level in five years, the bloc's border agency says.

An estimated 150,000 illegal crossings were registered by Frontex last year, the lowest amount since 2013.

It highlighted a sharp fall in the numbers crossing the Mediterranean to Italy, where a populist government has refused to allow rescue boats to dock.

But it said that arrivals in Spain had doubled for the second year in a row.

What do the figures show?

The number of people detected in 2018 was 92% below that of 2015, when Europe's migration crisis was at its peak.

The figure also fell by a quarter compared to 2017, with the biggest fall reported along the central Mediterranean route from northern Africa to southern Italy.

The number of illegal crossings detected there plummeted by 80% to slightly more than 23,000, Frontex says.

It added that the number of departures from Libya dropped by 87% in one year, and those from Algeria fell by nearly a half.

Frontex says the western Mediterranean route is now Europe's most active. The number of illegal arrivals in Spain - mostly from Morocco - doubled to 57,000 in 2018.

Meeting Spain's illegal migrants

The agency also gathered data on the gender and ages of those caught trying to enter the EU illegally.

Women accounted for 18% of them, it says, while nearly one in five said they were under the age of 18.

The figures differ from those recorded by the UN refugee agency (UNHCR), external which says that 123,109 illegal migrants arrived in the EU last year.

Frontex says this discrepancy is due to the fact that they cover all of the EU's external land borders whereas the UN primarily measure sea borders.

What's behind the changes?

The recent fall in the number of migrants attempting to take the central Mediterranean route to Italy follows the election of a populist government that has taken a hardline stance on immigration.

The government, a coalition between the right-wing League party and the anti-establishment Five Star Movement, came to power in June.

It has pursued a number of measures to prevent rescued migrants from landing on its shores.

In September, it passed a bill that was intended to make it easier to deport migrants and strip them of Italian citizenship.

The Italian government's tough immigration policies have drawn protests

Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has also frequently come into conflict with migrant rescue ship operators and has banned these ships from docking at Italian ports.

Italian policy is that migrants picked up at sea should be returned to Libya by that country's coastguard.

But charities and human rights groups say migrants face appalling conditions in Libya, where abuse at the hands of people-trafficking gangs are rife.

Officials have also warned that those crossing the Mediterranean face a more dangerous journey than ever before.

A migrant is rescued off the coast of Malta on Friday, where rescue ships are being denied permission to dock

In September, UNHCR said that while the number of people arriving in Europe had fallen, the number of deaths had risen sharply.

International Organization for Migration (IOM) data says that more than 2,000 people died or went missing making crossings last year., external

"The reason the traffic has become more deadly is that the traffickers are taking more risks, because there is more surveillance exercised by the Libyan coastguards," Vincent Cochetel, UNHCR's special envoy for the central Mediterranean, said at the time.

- Published3 September 2018

- Published4 September 2018

- Published11 September 2018

- Published20 September 2018

- Published26 February 2020