French frustrations with Macron boil over in angry debates

- Published

Will the French president's 'Grand Debate' defuse the yellow-vest protesters' rage?

Yellow-vest protests have rocked France for 15 weeks, and while the most dramatic scenes have been in Paris, much of the discontent has spread from the smaller towns in France, where people feel forgotten.

For the past month President Emmanuel Macron has toured the country, listening to local mayors and citizens as part of his grand débat - a big national debate.

He has also asked communities to come together and put forward their ideas for how to fix France.

One of those is Roubaix in France's north-east, where textile factories closed in the 1970s and almost one in three people is unemployed.

Marc Dubrul, who compered the Roubaix debate, says there is little trust in the president

"The people here don't trust Macron, they don't like him", says local activist Marc Dubrul, who runs a supper club that is feeding 150 people.

He has taken on the duty of compering Roubaix's debate, and dozens gather to voice their frustrations on the cost of living, fuel taxes and politics.

"I've worked for 40 years. I've done everything, and I've achieved nothing," one man shouts out.

Many in Roubaix complain of not having enough money to live on

The shouts get louder.

"I'm worried about the growing inequalities, the growing injustices, in this country".

They continue like this for hours.

No-one has enough to live on - from the employed to the unemployed and retired - and people are angry about it.

How Macron aims to make the debates work

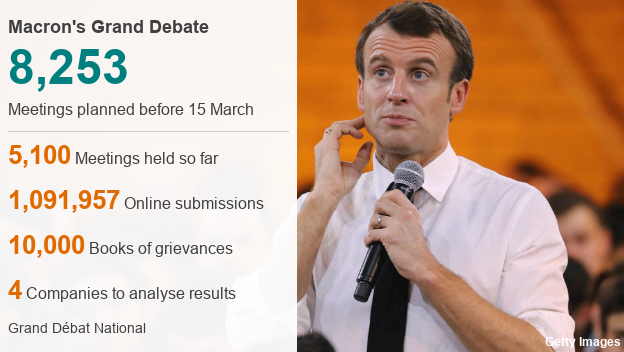

So far there have been more than 5,000 of these local gatherings held across France, with another 3,000 still to come.

During the meeting one of the town's residents sits quietly recording everything that is said.

This, and all the other debate minutes, will eventually be sent to the government to digest. But there is deep suspicion in Roubaix about the exercise.

"It's a lie," complains Mr Dubrul. "The president doesn't want to listen to the people, the yellow-vest movement isn't strong enough yet. We need more people on the streets".

A three-hour drive away is the small Normandy village where Mr Macron kicked off his grand débat - the aptly named Grand Bourgtheroulde.

He gathered 600 local mayors and listened for hours while they offloaded their grievances.

President Macron, as here in Grand Bourgtheroulde, has spent hours at a time listening to grievances

That trip has ignited people here and for weeks they have been coming to write down their frustrations in notebooks placed in the town hall.

These grievance books have been left across France, and 10,000 have already been filled and sent to the government, adding to the pile of reading that awaits Mr Macron and his team at the end of this long listening exercise.

Will Macron respond?

In a cafe across the road from the town hall Fanny Niquet and Chantal Huger reflect on his decision to get off his "Parisian pedestal".

"He has been very arrogant from the start," says Fanny.

Fanny (L) and Chantal believe the tension is so high that there is a risk of a civil war

They talk about the struggle of looking after their grandchildren, so their children can make ends meet.

"He needs to raise the low wages, so that people can afford to live", she says.

And if he doesn't act?

"There will be a civil war," they both claim, "a revolution". "There is too much tension now, people are radicalised," says Chantal.

Anger at government's tax and spend

It is a wet and freezing evening in the hills of the Loire valley in western France.

Bakers, butchers and builders crowd into a small hall, for a debate aimed at local artisans who work in and around the town of Tours.

They are the French bourgeoisie, and this should be safe territory for Macron. At the entrance of the hall his picture hangs high on the wall.

They talk for hours and become increasingly frustrated. Taxes are "too high" and welfare payments "too generous".

Béatrice Villemade fears she will have to close down her hairdressing salon

"This country has a problem with equality; we've been forgotten," shouts one builder.

One of their grievances is the yellow-vest protests themselves that have taken over the streets outside their businesses, and mean that people have stopped passing their shops.

Béatrice Villemade runs a hairdressing salon and has had to close it a dozen times because of the protests.

"I've lost 30% of my income. If the protests don't stop soon, I'll have to close," she complains.

Restaurant owner Charles Fourcaulx says they feel increasingly trapped by the high number of taxes.

Many of the yellow-vest protesters believe the Grand Debate is a waste of time

"We're left with the feeling that there's no future in France for people who want to start businesses," he says. "It's got to the point where I'm thinking of leaving France; taking my money elsewhere."

Grievances may differ, but there has been no avoiding the anger that runs deep across the country.

The grand débat is a long shot and will only work if Mr Macron truly listens to what has been said.

"This is no longer France," says one passer-by. "Now, we call it souffrance," using the French word for suffering.

- Published6 December 2018

- Published19 February 2019