Irish cult of relics a case of the head vs the heart

- Published

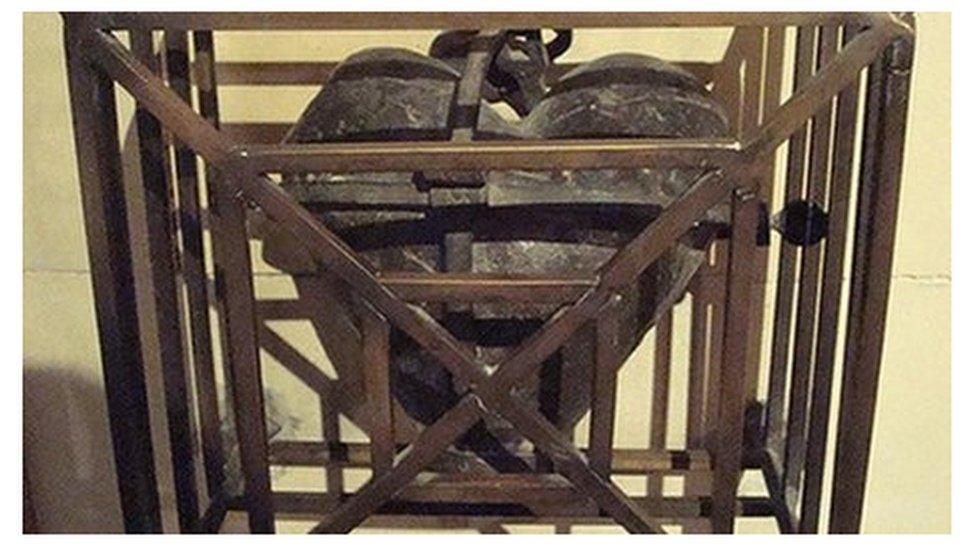

St Oliver Plunkett's head is on display at St Peter's Church in Drogheda

A severed head, a stolen heart, a bloody Valentine - they could be props from a bad horror film.

They are also among some of the more unusual items on public display as Christian relics in Irish churches.

Depending on your viewpoint, the decayed body parts could be considered irreplaceable historical artefacts or grisly tourist attractions.

But for believers, they are priceless religious treasures that provide physical links to saints and martyrs.

BBC News NI dissects some of Ireland's best-preserved examples.

The head of St Oliver Plunkett

The executed saint's head is on display in St Peter's Church in Drogheda, County Louth.

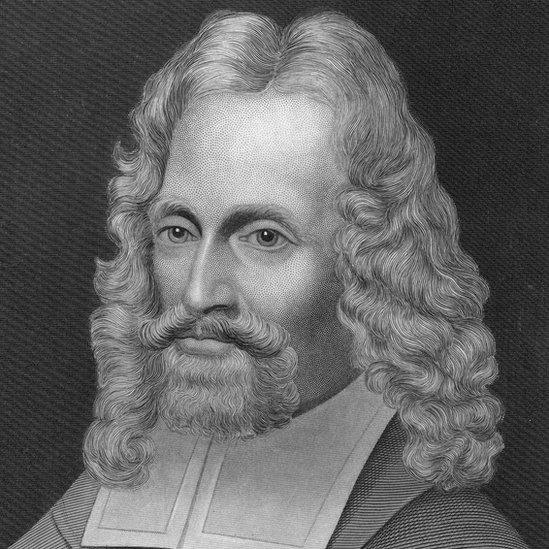

An artistic impression St Oliver Plunkett as Catholic Primate of All-Ireland

Oliver Plunkett (1625 -1681) led the Catholic Church in Ireland during once of its most turbulent periods, when Catholics faced persecution for practicing their religion in public.

Plunkett was a law-abiding diplomat who built bridges between Catholics and Protestants, according to historian Tommy Burns.

Nevertheless, he was falsely accused of treason in the "Popish Plot", a fictitious conspiracy to kill the Protestant Charles II.

Plunkett was hung, drawn and quartered in 1681. Catholics hailed him as a martyr and brought his severed head to Rome.

About 40 years later, the head was entrusted to an order of nuns in Drogheda led by a grand-niece of St Oliver.

They preserved it for 200 years, hiding the head and their own vocation from British authorities.

"The head of St Oliver was kept in a lovely ebony box, which fitted perfectly squarely on top of their grandfather clock in Dyer Street," says Mr Burns.

In 1921, the relic was placed in a shrine in the town's new church.

The head of St Oliver Plunkett is now a national shrine

St Oliver is now the patron saint for peace and reconciliation in Ireland.

Mr Burns admits keeping a severed head "is macabre to some degree" but he adds relics are a "tangible connection" to saints and a traditional part of Catholic belief.

The heart of St Laurence O'Toole

The heart of Dublin's patron saint is displayed in the city's Christ Church Cathedral.

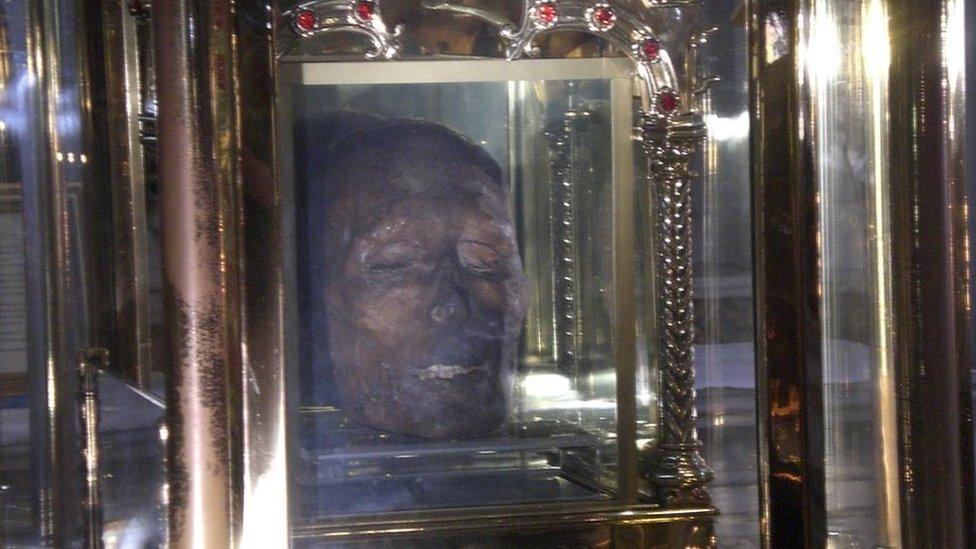

The stolen heart was recovered last year and placed back on display in Christ Church Cathedral

Laurence O'Toole was a 12th Century archbishop of Dublin whose tenure coincided with the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland.

He helped broker the 1175 Treaty of Windsor, a peace agreement between the English king and one of Ireland's last high kings.

He died during a peace mission to France and his heart was brought to back to Christ Church.

In 2012, a gang of thieves prised open an iron cage and stole the 800-year-old relic.

In 2012, thieves broke into an iron cage and stole the preserved heart of St Laurence O'Toole

Six years later, detectives received a tip-off that it had been buried in Phoenix Park.

According to one Dublin newspaper, the superstitious thieves began to believe the relic was cursed, external, blaming it for relatives' heart attacks.

The cathedral's head of education, Ruth Kenny, believes a gang member led officers to the spot, but she declined to comment on the newspaper's claims.

She pointed out the Anglican Church of Ireland considers the heart to be a "historical artefact", not a relic.

The blood of St Valentine

Purported remnants of the patron saint of lovers repose in Dublin's Whitefriar Street Church.

St Valentine's Shrine in Whitefriar Street Church

Remains, including a "small vessel tinged with his blood", were excavated in Rome in the 19th Century, according to the Carmelite Order which has custody of the relics.

In 1836, the Pope gifted the relics to an Irish Carmelite priest who impressed during a preaching tour of Rome.

However, much like mystery admirers who borrow his name every 14 February, there is confusion over Valentine's identity.

The most romantic theory suggests he was a third Century Roman priest martyred for arranging secret marriages for soldiers.

Another suggests Valentine was a former Bishop of Terni, external beheaded for converting Romans to Christianity.

With several incarnations of Valentine, it is perhaps not surprising Dublin is one of many European cities that claims his relics, including Madrid, Vienna and Rome.

Rome's Basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin displays a skull crowned with flowers labelled "St Valentine"

The Carmelites acknowledge the other claims, external arguing it was customary to disperse saints' body parts as separate relics.

The arm of St Patrick

Ireland's patron saint's arm bone is said to have been preserved in a silver reliquary owned by St Patrick's Church in north Belfast.

The silver gilt reliquary is currently on loan to the Ulster Museum

The reliquary is thought to date back to the late 12th Century, shortly after remains were recovered in Downpatrick and hailed as the bones of St Patrick, who died seven centuries earlier.

In 1856, the Bishop of Down and Connor opened the reliquary to find it contained no bone, just a piece of wood with wax seals, about the length of a forearm.

The church suggests the wood once held the bone in place, but the relic may have been "worn away through constant use".

"It was customary for the keeper of the relic to pour water through the elbow termination of the shrine, which, touching the relic passing through, flowed out at the fingers and was used as a cure for various diseases," the parish website, external states.

Visitors flocked to "St Patrick's grave" on 17 March, but there is much doubt over the location of his burial site

Niamh Wycherley, author of The Cult of Relics in Early Medieval Ireland, said that many Christians historically believed relics had "supernatural powers".

"Relics were used to affect changes in weather, to heal ailments, to ensure victory in battle, for fertility - basically anything you might pray to God for."

She said that relics were part of "all major world religions" but they served a particular role in regulating Christianity in Ireland.

"There were a number of edicts in the early medieval Church... disseminated from Rome, saying a church could not be consecrated without a relic."

Without modern authentication procedures, it was difficult to verify if the remains were genuine.

Ms Wycherley doubts the veracity of most if not all of Ireland's early medieval relics.

"You could basically make up any relic you wanted to. Now, this is not to say that people did that all the time, but certainly there are very suspicious circumstances surrounding some of them."

Niamh Wycherley is an author and postdoctoral fellow at the National University of Ireland

St Patrick's shrine is displayed in St Patrick's Church on special occasions, but is currently on loan to the Ulster Museum, which admits "proof is lacking" on its origins.

Ms Wycherley does "not believe" remains recovered in Downpatrick are likely to be St Patrick but argues that does not expunge their significance.

"It doesn't really matter whether they were 'real' or not, because it's the importance they had to the society and to the particular culture," she said.

"If some imbue a particular item with importance, then it's important."

- Published14 February 2019

- Published26 April 2018