Ukraine election: Why comic Zelensky is real threat to Poroshenko

- Published

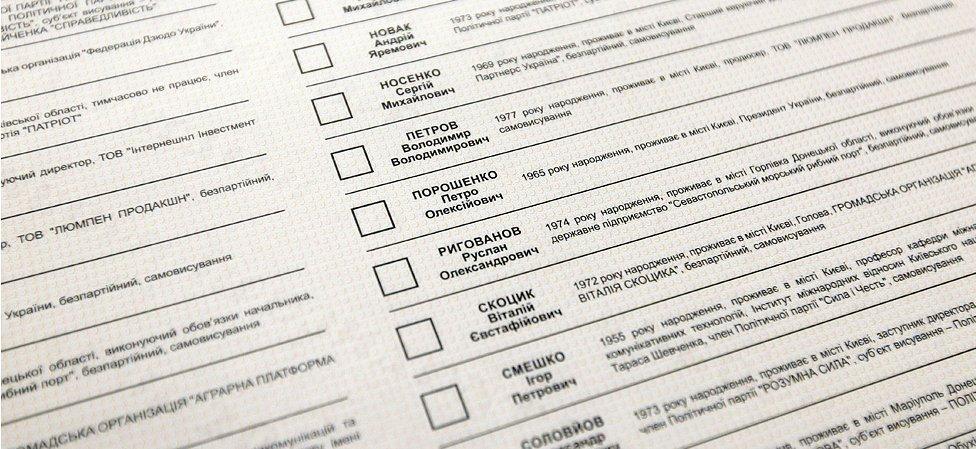

Voters have 39 candidates to consider on a very long ballot paper

Could Ukraine be the next big country to see an anti-establishment "outsider" candidate sweep to victory?

The world is getting used to such stunning triumphs, in a time of volatile politics and general insecurity. We've seen it in France (Emmanuel Macron), Italy (the rise of Five Star) and the United States (Donald Trump).

Ahead of Ukraine's 31 March presidential election an anti-establishment comedian, Volodymyr Zelensky, is leading opinion polls.

"Zelensky against the system... a comedian against Ukraine's deep state," is how Alexander Motyl, a Ukraine expert at Rutgers University in the US, describes it.

This is the first time Ukrainians are choosing a new president since the momentous events of 2014.

Former pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych was toppled in the February 2014 Maidan Revolution, which cost more than 100 lives. Then came Russia's annexation of Crimea and a Russian-backed insurgency in the east.

Volodymyr Zelensky continued performing with his comedy group during the campaign

Within weeks, one of Ukraine's wealthiest oligarchs, confectionery tycoon Petro Poroshenko, won a snap presidential election in May 2014 unusually in the first round, with nearly 55% of the vote.

The Ukrainian president has significant powers over security, defence and foreign policy. So he/she is not just a figurehead; the ex-Soviet republic's system is described as semi-presidential.

If no candidate gets more than 50% on Sunday, the top two will fight it out in a second round on 21 April.

Today many Ukrainians remain poor and disillusioned with the country's politics. They had hoped to see much more economic progress and determined action against corruption after the 2014 upheaval.

Key economic sectors - especially energy and heavy industry - remain in the hands of oligarchs powerful enough to fix prices and intimidate challengers.

Independence Day parade: The deadlocked eastern conflict is not a hot election topic

The EU and Russia are nervously watching this election. The next president will inherit a deadlocked conflict between Ukrainian troops and Russian-backed separatists in the east, while Ukraine strives to fulfil EU requirements for closer economic ties.

The EU points out that some 12% of Ukraine's 44 million people are disenfranchised, largely those who live in Russia and in Crimea, which Russia annexed in March 2014.

The comedian who would be president

But Anders Aslund, a Ukraine expert at the Atlantic Council think-tank, says the conflict with Russia "is not at all a factor" in this election campaign.

Who are the main contenders?

Of the 39 names on the ballot paper just a handful are political heavyweights.

Mr Aslund says "many want to make a name for themselves for the October parliamentary elections" and entering the presidential race "gets them name recognition". "There is also the vanity factor - it doesn't cost so much to run," he told the BBC.

Newcomer Volodymyr Zelensky, 41, has surged to the front in recent months, according to opinion polls, which put him on about 25%.

He aims to turn his satirical TV show into political reality: he portrays an ordinary citizen who rises to the presidency by fighting corruption, in the series Servant of the People.

That show is a hit on Channel 1+1, owned by billionaire oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky, a leading opponent of President Poroshenko. So Mr Zelensky is generally seen to be close to Mr Kolomoisky.

Mr Zelensky has run a skilful, modern campaign relying on social media, Mr Aslund said. But there are worries about his lack of political experience.

"It's very different - he is appealing to young voters, aged below 40. He doesn't have a detailed programme, but he is not a populist," Mr Aslund said, describing the comedian as "more like Macron than Trump".

President Poroshenko's popularity has plunged since 2014

President Poroshenko, 53, has the slogan "Army, Language, Faith" - an appeal to conservative, nationalist Ukrainians.

Among his achievements, he points to: backing for the military, which has kept the Donbas separatists in check; an Association Agreement with the EU, including visa-free travel for Ukrainians; independence for the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, ending centuries of Russian control.

But his campaign has been dogged by corruption allegations, including a scandal over defence procurement, external, which erupted last month. "It's a very hard slog to get him to tackle corruption, and the West has a rather cold attitude to him," said Mr Aslund.

An EU Commission report in November, external praised some of Ukraine's reforms under Mr Poroshenko, such as in healthcare, pensions and public administration.

But judicial reforms were too slow, the report said, and "there have been only few convictions in high-level corruption cases so far". Too often attacks on civil society activists went unpunished, it said.

Yulia Tymoshenko: A veteran campaigner and long-standing rival of Mr Poroshenko

Opinion polls put Mr Poroshenko roughly level with Yulia Tymoshenko, 58, on about 13%.

She is a veteran campaigner, who played a leading role in the 2004 Orange Revolution - Ukraine's first big push to ally itself with the EU, defying Russia.

She has served as prime minister and ran for president twice before, in 2010 and 2014.

Her core electorate is "elderly, rural and female", Mr Aslund said. Last year she engaged thousands of people in an ambitious constitutional reform drive, aiming to turn Ukraine into a full-blown parliamentary democracy.

But besides that, according to Mr Aslund, "she had little new to say" in her campaign. She pledged to lower gas prices, boost pensions and freeze privatisation of agricultural land.

There are no party logos or colours next to the rivals' names

She is furious that a candidate called Yuriy Tymoshenko is also in the race. She accused Mr Poroshenko of using him as a "puppet" to confuse voters and damage her chances. Her namesake, however, insists that voters "will easily understand where is Yulia and where is Yuriy".

She has also traded invective with Mr Zelensky, likening him to an iconic Soviet-era cartoon character with big ears, called Cheburashka. She said he was like a "Cheburashka borscht [beetroot soup] - creative... but not tasty".

He riposted that it was better than being "a sour borscht that was cooked yesterday" - an insult widely quoted on the web.

Meanwhile, Radical Party candidate Oleh Lyashko - a nationalist - called Ms Tymoshenko a "Moscow cuckoo", and she retaliated by branding him "Poroshenko's yapping Chihuahua".

Ukraine's relations with Russia remain hostile and this time Moscow is reckoned to have little leverage over Ukrainian voters.

The most pro-Russian voters are in the separatist-controlled east and Crimea. But separatist-held areas are boycotting the election and Crimea has been annexed by Russia.

Polls suggest that a Russia-friendly candidate - Yuriy Boyko, 60 - is in fourth place. He says he would "normalise" relations with Russia - the neighbouring power that has most dominated Ukraine's history.

- Published20 March 2019

- Published27 January

- Published7 February 2019

- Published24 February 2019

- Published11 February 2019

- Published28 December 2018

- Published5 January 2019