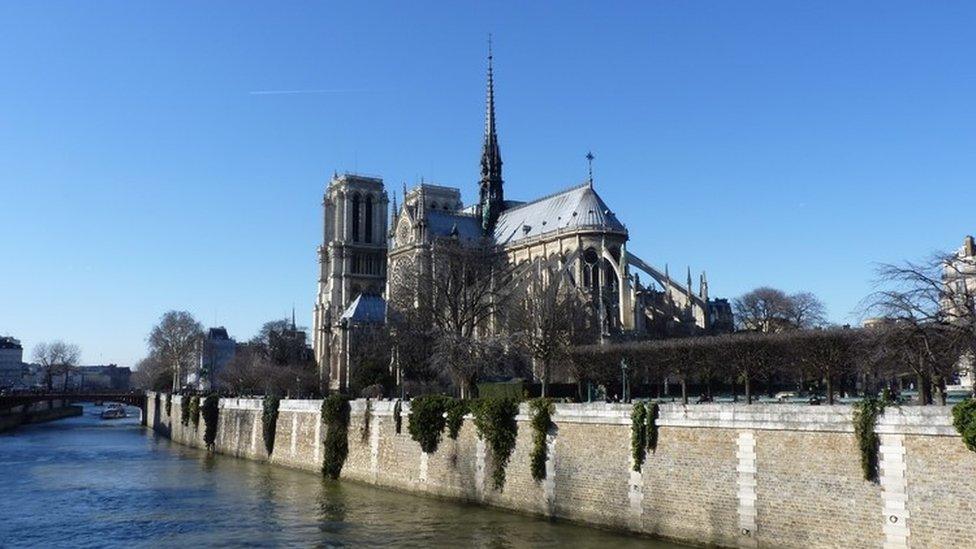

Notre-Dame fire: How will the cathedral be restored?

- Published

Hundreds of millions of euros have been pledged to help rebuild Notre-Dame

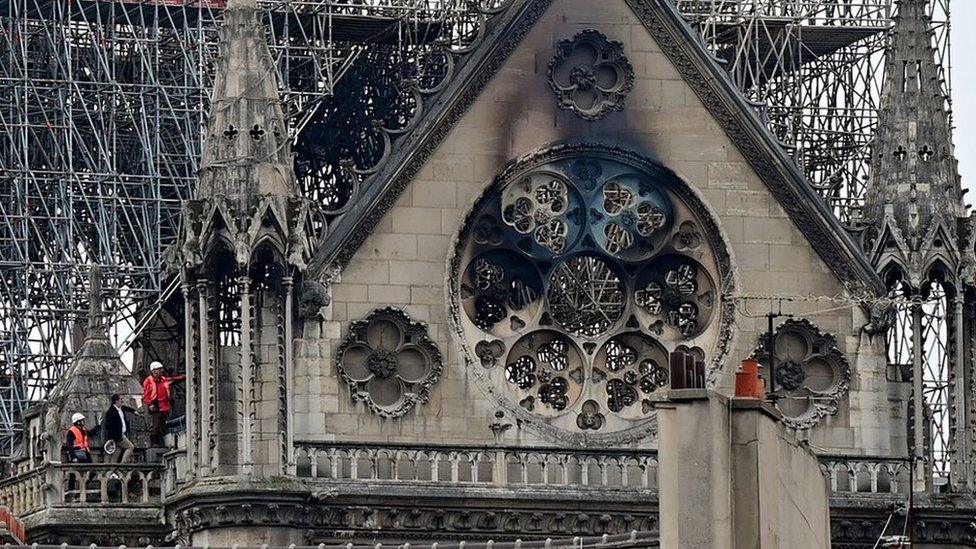

The dramatic sight of Notre-Dame being ravaged by flames on Monday captivated people around the world.

The French cathedral, which dates back more than 850 years, has been partially destroyed despite the best efforts of firefighters who worked throughout the night.

Now, as investigators work to establish the cause of the blaze, attention has turned to how the building can be repaired.

A number of companies and business tycoons have pledged hundreds of millions of euros between them towards the restoration effort.

So can the famous landmark be returned to its former glory?

John David is better positioned than most to judge whether the famous cathedral can be saved.

The master stonemason was part of a team of craftsmen who worked to rebuild England's York Minster cathedral when it was badly damaged by fire in 1984. It was set alight after it was hit by lightning, causing £2.25m ($3m) in damage.

"We went in and there were piles of charred timbers on the floor," he recalls. "There was black ash and soot and the whole building smelt of smoke. There was a sort of gloom in the place."

But he says the team was confident it could be repaired and he feels equally optimistic about Notre-Dame. "There was no fear about putting it back and I imagine that's the same in this case" he says.

"It's quite achievable to see it [restored] and it's an opportunity to show that this work can still be done," he says.

John David helped repair York Minster after it was hit by a lightning strike in 1984

Mr David says the restoration team must first remove the Notre-Dame's burnt scaffolding. There were extensive renovation works taking place at the time of the fire and a huge scaffold was covering much of its exterior.

"The scaffolding will be in the way and will have to be delicately taken down because it's suffered with the heat," he says.

He explains that a protective cover will then need to be placed over the cathedral to shield it from the wind and rain.

Any fallen timber and other debris inside the cathedral will need to be cleared out, Mr David says. But this debris won't just be removed and forgotten about.

"Early phases of the work will include the archaeological recording of surviving fragments of timber, stone and artworks," says Dr Kate Giles, from the University of York's department of archaeology.

"This will enable the Notre-Dame team to salvage what can be reused and provide crucial evidence for the design of new fabrics in the building," she says.

The fire at Notre-Dame raged for more than 15 hours

Surveying the damage

Once the cathedral is cleared, experts say a thorough survey will need to be carried out to establish the extent of the damage and to ensure it is safe to re-enter.

"Safety will be the prime concern," says Dr Amira Elnokaly, a lecturer in archaeology at the University of Lincoln. "There should be critical inspections to avoid any risks of further collapses or falling debris."

The survey will then turn to the stonework at the top of the cathedral near the roof.

"The upper stone work, the vaulting and the top windows, will have been baked and the temperature will have spoiled and weakened the stone," says Paul Binski, a history of medieval art professor at the University of Cambridge.

"The first thing they're going to do is a massive survey of the stone," he says. "They're going to have to scaffold the whole building and look very closely at its condition."

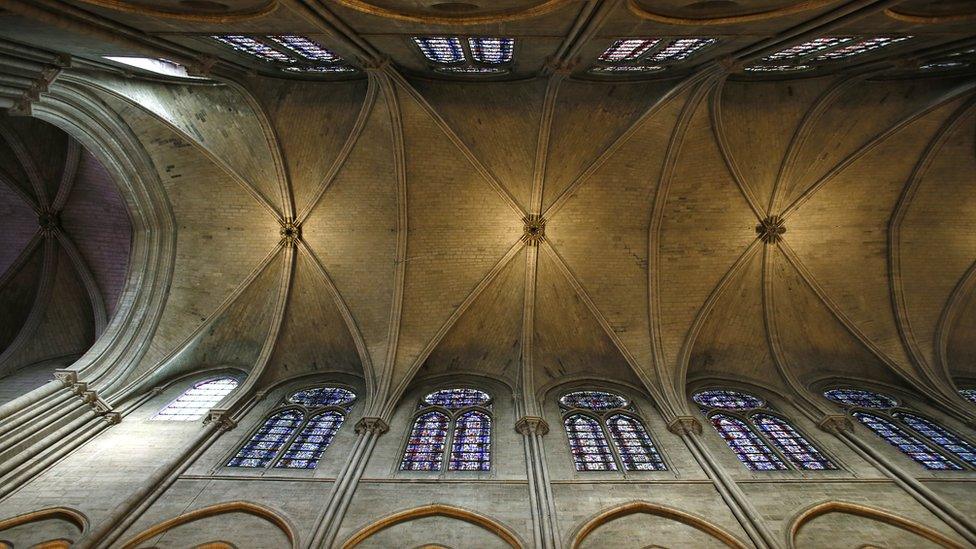

A view of the stone ceiling inside the Notre-Dame before the fire

This is because the stone ceiling will have taken the brunt of the impact when the timber roof above collapsed, experts suggest.

"The 19th Century spire, the 19th Century roofing, what will have happened is that these will have crashed down on to the stone vault underneath, the rib vault, which rises to 108ft (33m)," Prof Binski says.

"The vaulting system will have shielded what's in the church from the inferno above," he adds. "Of course, it will likely have come down in parts, but it will have done a major protective job."

Indeed, images appear to show that the pulpit, pews and altar have escaped the fire largely unscathed.

If some of the stonework does need to be replaced then, Prof Binski says, the team will probably use traditional methods to do so.

"It's important to look at the original construction methods and try to emulate them." he explains. "This involves building an awful lot of wood scaffolding inside the church because [stone vaulting] is built around a kind of wooden structure - like a mould.

"They're not built with cement but with something that's rather like putty."

Prof Binski says that if a large amount of the stone vaulting needs to be replaced it could be "the biggest vaulting operation of this type undertaken since the Middle Ages".

"The question is how long this is going to take and my guess is 5-10 years minimum to get the whole thing re-vaulted," he says.

This estimate highlights the challenges facing the restoration team if they are to meet President Emmanuel Macron's suggested timescale. The French leader wants Notre-Dame rebuilt by the time Paris hosts the Summer Olympics in 2024.

But Mr David says this is a feasible goal. "I don't think it will take 10 years," he says. "It might take two years to decide what to do, but [five years] is quite achievable."

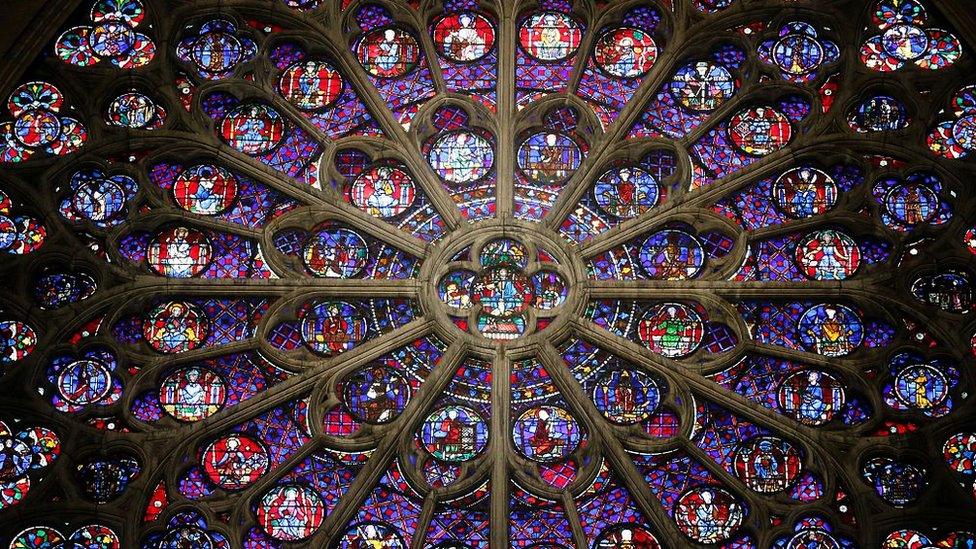

Photos from inside the cathedral appear to show that at least one of its famed rose windows has survived, although there are concerns for some of the other stained-glass windows.

So how will the experts protect and restore these?

"They will do an initial survey when they establish what the highest priorities are in terms of historical and artistic significance," says Sarah Brown, an expert in stained glass windows.

At least one of the three famous rose windows is reported to have survived the fire

"I suspect all of the windows will require some attention because a fire of that size will generate so much smoke and soot," she says. "Even if the windows are in relatively good order they're certainly going to require cleaning.

"The biggest problem will be the heating up and then the rapid cooling down of the glass as it's been struck by water from the cannons," Ms Brown explains. "This will bring about thermal shock that will cause micro-fractures in the glass which will be really difficult to stabilise."

She continues: "They will need to re-lead these windows because the lead that keeps it all together will no longer hold good, but you cannot even attempt that until you've stabilised the heat-induced micro-fractures in the glass.

There are modern adhesives that can do that, however."

And what if one of the cathedral's windows has been completely destroyed? "The big question then is how they go about re-glazing the building," Ms Brown says.

"You can't leave it with nothing in the window," she says. "Some might call for a new stained glass window but it's too early to say what should be done. Windows can be remarkably resilient, so let's hope that's been the case here."

- Published16 April 2019

- Published16 April 2019

- Published16 April 2019

- Published15 April 2019

- Published5 March 2018