The fake French minister in a silicone mask who stole millions

- Published

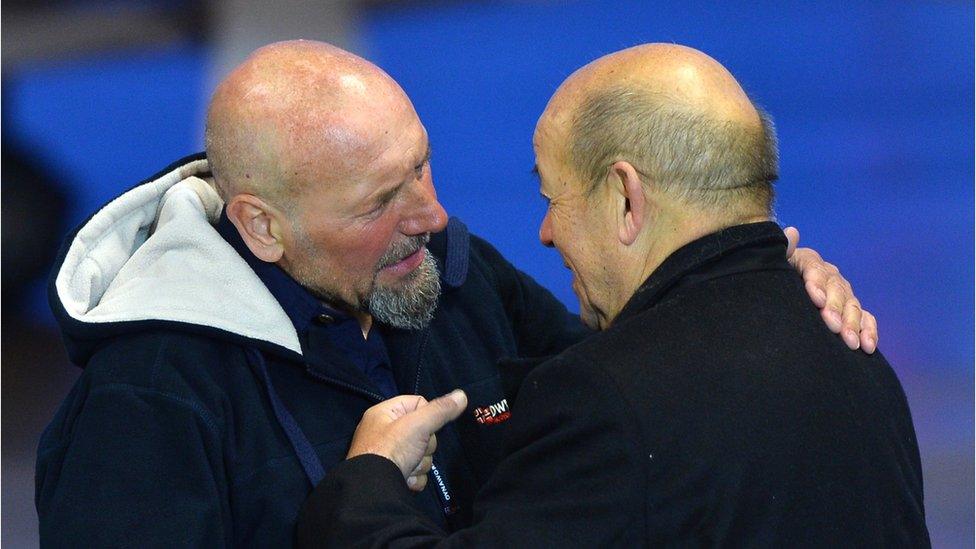

The real Jean-Yves Le Drian is on the left, while the fake Le Drian sits behind a desk in a makeshift office

Identity theft is said to be the world's fastest-growing crime, but in sheer chutzpah there can be few cons to match the story of the fake French minister and his silicone mask.

For two years from late 2015, an individual or individuals impersonating France's defence minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, scammed an estimated €80m (£70m; $90m) from wealthy victims including the Aga Khan and the owner of Château Margaux wines.

The hustle required targets to believe they were being contacted by Mr Le Drian, who then requested financial help to pay ransoms for journalists being held hostage by Islamists in the Middle East.

Since France officially does not pay ransoms to hostage-takers, the fake Le Drian assured payments could not be traced and asked for the funds to be placed in a bank in China.

Many of those approached smelled a rat and rang off.

But, some didn't - enough for it to become one of the most outlandish and successful rackets of recent times.

Why impersonate a minister?

"Everything about the story is exceptional," said Delphine Meillet, lawyer to Mr Le Drian, who is now France's foreign minister.

"They dared to take on the identity of a serving French minister. Then they called up CEOs and heads of government round the world and asked for vast amounts of money. The nerve of it!"

Why Jean-Yves Le Drian was chosen has not been fully explained.

Presumably the fact that as defence minister he might be in charge of ransom demands was part if it, but another factor may have been his relative obscurity.

Yves Le Drian (R) has played a role in hostage dramas. Here he is in 2014 welcoming home Serge Lazarevic after a hostage ordeal in Mali

Before 2012, Mr Le Drian had been a Socialist politician in Brittany. Someone with a higher international profile would have been harder to carry off.

Whodunnit?

The case is now under judicial investigation in France, with suspicions centring on a convicted French-Israeli con-artist called Gilbert Chikli.

He is currently in jail in Paris following extradition from Ukraine and faces charges of organised fraud and usurpation of identity.

Chikli, of Tunisian Jewish background, grew up in the working-class Belleville neighbourhood of northeast Paris.

How easy is it to fake a famous face?

The tool can edit videos of people speaking and make them say something they have not

In 2015, Chikli was found guilty of scamming money out of French corporations by pretending to be their chief executive. But by this time he was living in Israel, which doesn't often extradite its nationals.

According to investigators, Chikli's first move against the minister came shortly after his conviction in a bid to get the Tunisian government to pay for a number of Tiger helicopters that had never actually been ordered.

A contract apparently signed by the minister demanded millions of euros, but was spotted as a fake at the last moment.

Gilbert Chikli grew up in a working-class area of Paris, but wound up in 2017 in a Ukrainian court

The fraud then switched direction, targeting "friends of France", who were asked to contribute to the ransoms.

According to Ms Meillet, there were scores of calls to business leaders and heads of African governments, but also to church leaders such as the Archbishop of Bordeaux and charities like the Aids foundation, Sidaction.

How the scam worked

The system started with an initial telephone call from someone claiming to be a member of Mr Le Drian's inner circle, such as his special adviser Jean-Claude Mallet. This person would then arrange a conversation with the "minister" himself.

Initially these "ministerial" calls were also over the phone. But then - in an effort to be more convincing - the scam went up a level, to video.

Now the fake Le Drian not only had to sound like the defence minister, he had to look like him, too.

So, in meetings arranged on Skype, the fraudster wore a custom-made Le Drian mask and sat in a facsmile of Le Drian's ministerial office, complete with flags and portrait of then-President François Hollande.

Victims of the scam were taken in by the fake office as well as the mask

The ruse would still have been detectable, but the gang - it's assumed they were several - had the impostor badly lit and at some distance from the camera.

They also made sure the connection was bad and only lasted a short time - just enough to put out the bait.

"Looking back now I ask myself a lot of questions. But it did look like him!" Guy-Petrus Lignac, of the Petrus wine dynasty, told a France Télévisions documentary.

"And he was asking for my help as a service for the state! It's scary because maybe if he had asked for less money, I might have said yes."

Ms Meillet has a long list of victims whose names are attached to the judicial dossier.

For obvious reasons none wished to talk. Of the €80m that was scammed, more than half the sum came from an unnamed Turkish businessman. The Aga Khan lost €18m.

One who did not fall for the trap was Senegalese leader Macky Sall.

Senegal's president, here visiting President Macron in 2018, was on familiar terms with the minister and smelled a rat

This was because the fake Le Drian made the basic error of addressing the president with the polite French vous. In fact the two men know each other well, and when talking together use the familiar tu.

How Chikli was brought back to France

Chikli's luck ran out in August 2017 when he made the mistake of travelling to Ukraine.

Arrested at the request of the French, he told police he was on a pilgrimage to the tomb of a well-known rabbi. But on his phone was evidence he had come to buy a mask.

In prison in Kiev, Chikli lived up to his reputation as a man of massive narcissism.

He paid guards to get him a fridge stocked with steaks and vodka, and then showed it off in a foul-mouthed, social media video in which he also taunted the French justice system.

That may have been a bad idea. Released, he was almost immediately re-arrested and this time extradited to France.

There the story would normally end, except for a strange coda.

Because earlier this year, with Chikli safely behind bars, the con started again.

Reports began to arrive at embassies that once again a fake Le Drian, by now French foreign minster, was trying to finagle money out of influential "friends of France".

In February, three French-Israeli citizens were arrested near Tel Aviv.

For now the calls have stopped.

But the suspicion has been raised that, far from there being a single con-artist, maybe there are several: a whole gang schooled in the art of being Jean-Yves Le Drian.

Correction 25th June 2019: An earlier version of this article wrongly said that Israel refuses to extradite its nationals and this has since been amended.