Where does Turkey's S-400 missile deal with Russia leave the US?

- Published

The S-400 is highly sophisticated - but incompatible with Nato's systems

After months of signals and threats the moment has finally come. The first elements of the Russian-supplied S-400 surface-to-air missile system have arrived in Turkey. Now Washington must decide what it is going to do.

On the face of it the American decision has already been taken.

Washington's position is simple. It does not want Turkey to buy the Russian system. And if Turkey does then it will not get the 100 or so US F-35 warplanes - America's most sophisticated warplane - that it has on order.

Already the training of Turkish pilots and mechanics in the US has been suspended.

The first few Turkish F-35s which have already been "delivered" but that are still in the US will not be going anywhere soon.

And the Pentagon has made it clear that if the S-400 purchase goes ahead then Turkey will be removed from the F-35 programme altogether.

Turkey is a partner country in this programme. Its aviation industry manufactures hundreds of parts for the aircraft and it is also slated to be a regional maintenance hub for the F-35's engines.

All of this is in jeopardy. The US and the aircraft's manufacturers are already investigating how they can move production to other countries.

So why is Washington so concerned about Turkey buying the S-400?

For a start it is almost unprecedented for a Nato country to buy such a sophisticated piece of Russian military hardware. Greece operates the Russian S-300 but these it obtained indirectly. They were purchased by Cyprus and transferred to Greece after Turkish objections.

The S-400 system is highly sophisticated; this is an area in which Russian technology is impressive. But there are practical problems too.

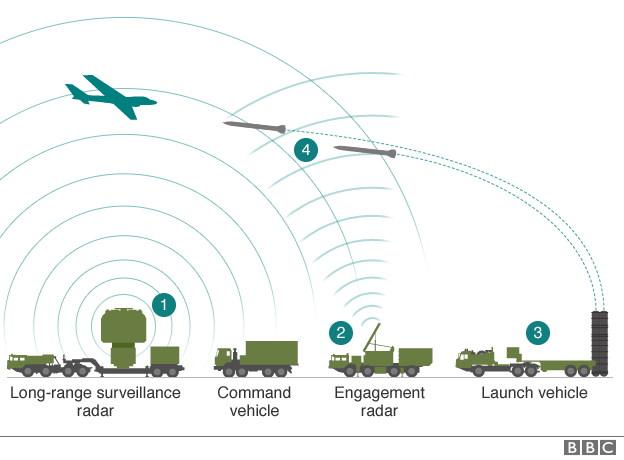

How does the S-400 work?

Long-range surveillance radar tracks objects and relays information to command vehicle, which assesses potential targets

Target is identified and command vehicle orders missile launch

Launch data are sent to the best placed launch vehicle and it releases surface-to-air missiles

Engagement radar helps guide missiles towards target

The point about air defences is that they rest not upon a single weapons system but a package of various missiles, radars and so on capable of engaging aircraft, missiles or whatever at various ranges and altitudes. Thus they all have to be compatible with each other.

Nato has done a lot of work helping the Turks to improve their overall system but the S-400 cannot easily be integrated with it.

In purely military terms the purchase makes limited sense.

Nato, in its initial response to the delivery, has made exactly this point, raising concerns about the inter-operability of the system, while trying to strike a positive note by commenting that Ankara remains interested in developing long-range air and missile defence systems with several allies.

But the most pressing concern for the Americans is security.

They fear that if Russian technicians are in Turkey for training and calibration of the S-400 then they may gain all sorts of data on the F-35, if Turkish F-35 jets are operating in the same air-space.

F-35s on HMS Queen Elizabeth carry out the first "rolling" landing.

The S-400's powerful radars will be able to monitor the aircraft closely despite its stealthy characteristics. For all the hype about stealth, no aircraft is invisible.

The S-400 purchase raises fundamental political and strategic issues too.

Just what signal does it send about Turkey's place in the Nato alliance if it is buying some of its most important defensive weaponry from Russia; a country that many Nato governments now see as a resurgent threat to the West?

The purchase also raises questions about decision-making in the Trump Administration and the mixed messages that it sends. The Pentagon line has been crystal clear and initial actions to warn the Turks have already been taken.

But after a recent meeting between Donald Trump and his Turkish counterpart the US president seemed to blame the whole affair on his predecessor - President Barack Obama - for failing to sell US air defence missiles to Turkey.

Mr Erdogan (left) seems confident that Mr Trump will not impose sanctions

The Turkish president clearly went away convinced that he could go ahead with the missile deal with Moscow with relative impunity.

Underlying it all is a fundamental shift in Turkey's geo-strategic outlook. The motivating factor can be summed up in one word - the Kurds. And the change has been as much due to US policy as anything else.

Turkey has watched with deep concern as various US interventions - in Iraq and Syria - have strengthened Kurdish groups whom Ankara regards as terrorist separatists who threaten the integrity of Turkey itself. It is no exaggeration to say that this is Turkey's number one security concern.

Indeed Washington had to rely upon allied Kurdish forces in Syria in the fighting against the Islamic State group since they were the most capable fighters available.

Turkey's concerns about Syria and the Kurds have encouraged its rapprochement with Moscow. Ankara seems to have decided that though its interests and those of Russians by no means coincide, the US is in retreat, and Russia is the regional player with which it must deal - at least for the time being.

The fundamental question is where this potential crisis goes. Do the Americans back down? Or will this become a turning point in Turkey's evolution as a more semi-detached member of the Atlantic Alliance?

- Published12 July 2019

- Published15 October 2018