Arctic wildfires: How bad are they and what caused them?

- Published

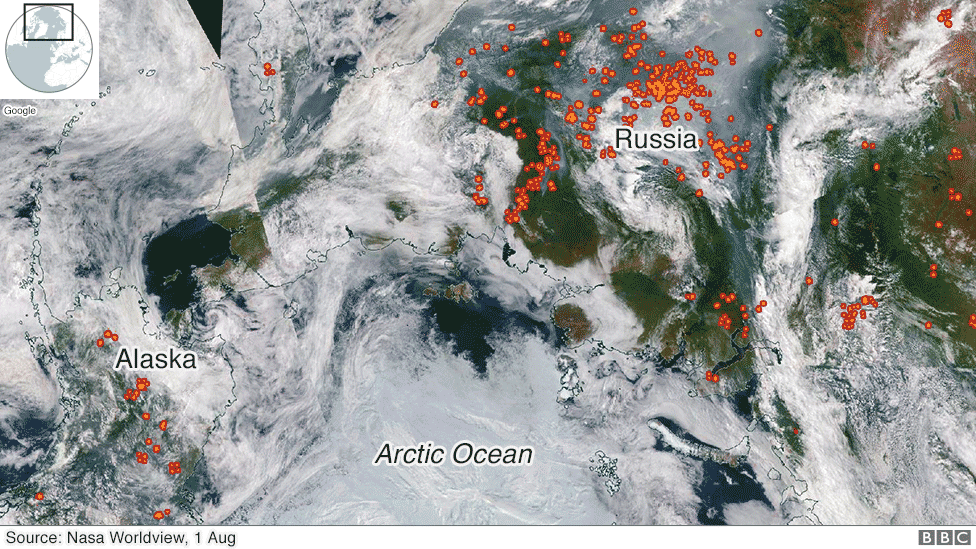

Wildfires are ravaging parts of the Arctic, with areas of Siberia, Alaska, Greenland and Canada engulfed in flames and smoke.

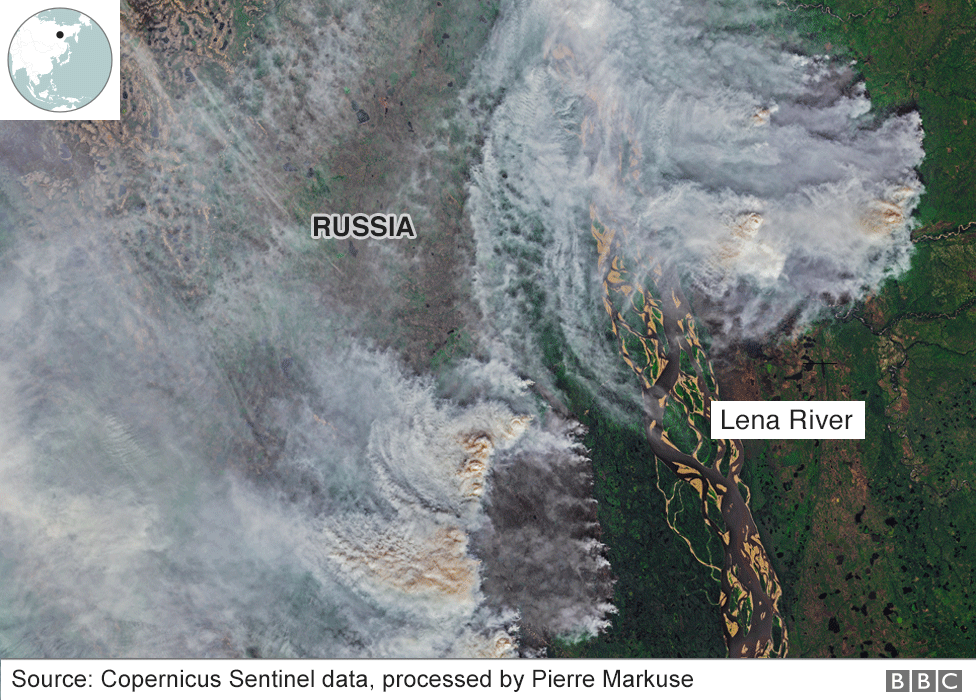

Satellite images show how the plumes of smoke from the fires, many caused by dry storms in hot weather, can be seen from space.

While wildfires are common at this time of year, record-breaking summer temperatures and strong winds have made this year's fires particularly bad.

They are now at "unprecedented levels", external, says Mark Parrington, a wildfires expert at the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (Cams).

Where has been affected?

Eastern Russia and Alaska, both within and outside the Arctic Circle, have been particularly badly affected.

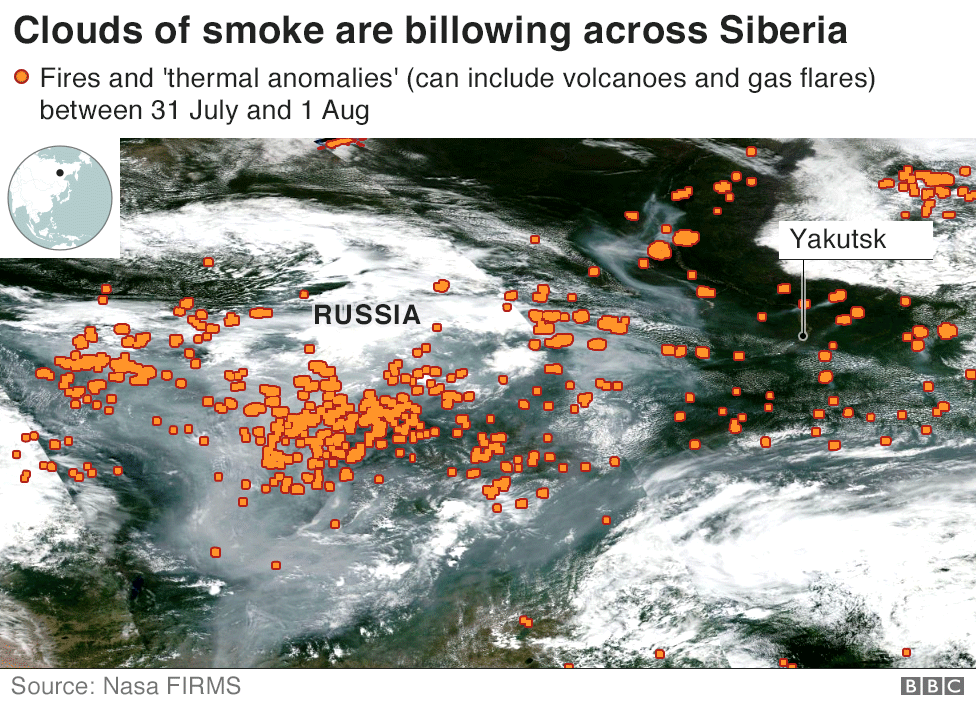

Russia's Federal Forestry Agency says more than 2.7m hectares (6.7m acres) of remote forest are currently burning across six Siberian and eastern regions., external

However, Greenpeace Russia says as many as 3.3m hectares are burning, external - an area bigger than Belgium.

Smog has prompted several regions to declare states of emergency and smoke has blown across major cities like Novosibirsk, blotting out the sun and making it difficult for some people to breathe.

The smoke from the Siberian fires has even spread to Alaska and parts of the west coast of Canada. , external

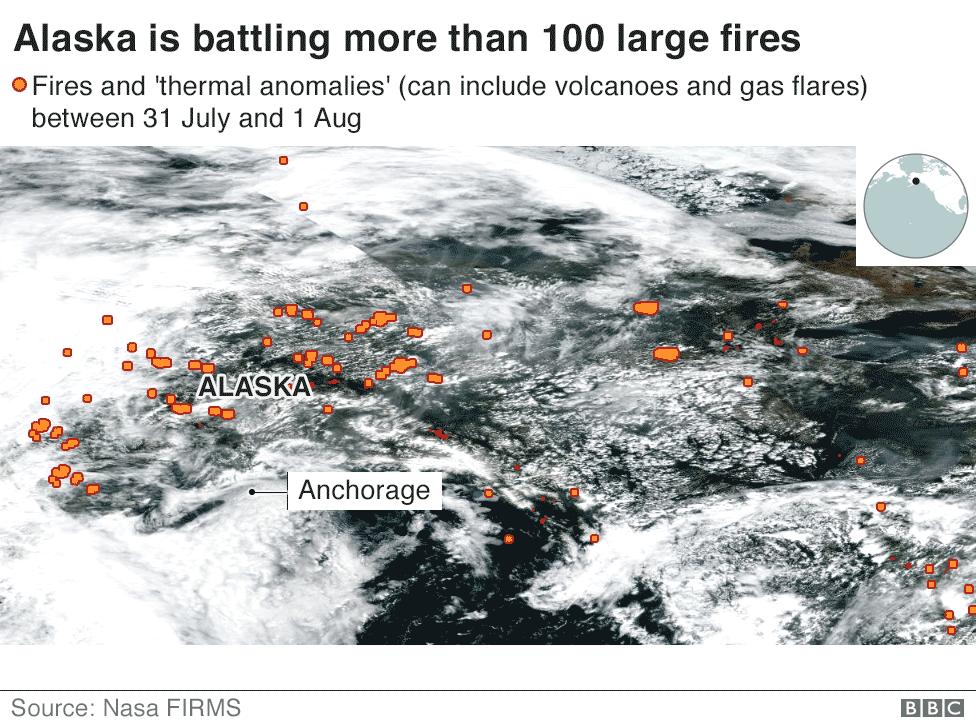

In Alaska, as of 31 July, 105 large fires had burned more than 0.7m hectares (1.78m acres).

The majority of the blazes were caused by lightning strikes, according to the Alaska Interagency Coordination Center., external

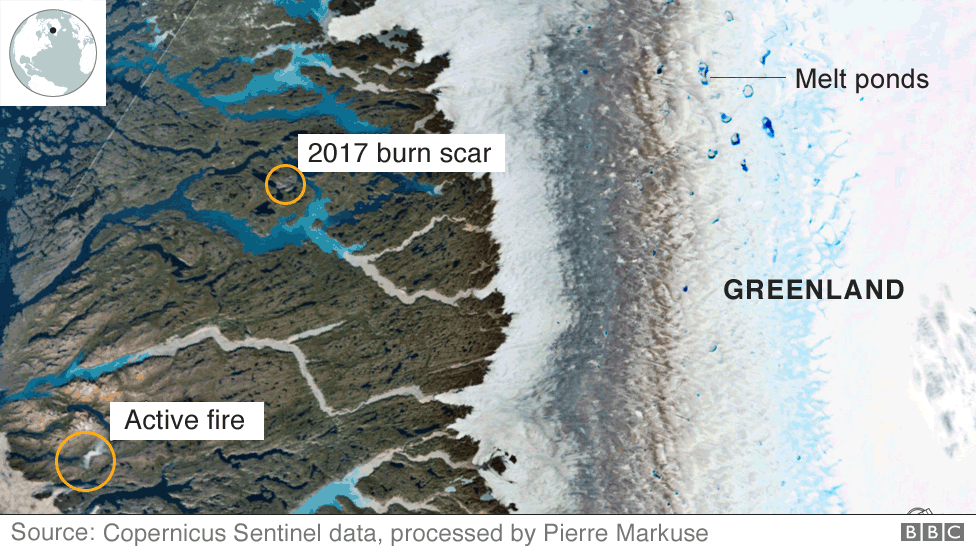

Greenland is also battling a fire in Qeqqata Kommunia, close to the Arctic Circle Trail, popular with hikers.

The area has been experiencing a heatwave, which has also meant the sea ice has been melting at a fast rate., external

Canada's Arctic is also suffering. One large wildfire in the Northwest Territories, inside the Arctic Circle, has burned at least 45,500 hectares (112,000 acres), external according to the Northwest Territories Environment and Natural Resources agency, although the area is likely to be bigger.

What has been the impact?

The wildfires are not just having an impact on the ground. They release harmful pollutants and toxic gases into the atmosphere.

Thick smoke is visible on satellite images and distinguishable from every-day clouds across vast areas of the Arctic.

Nasa has traced the megatons of harmful particles in that smoke - and where they have gone.

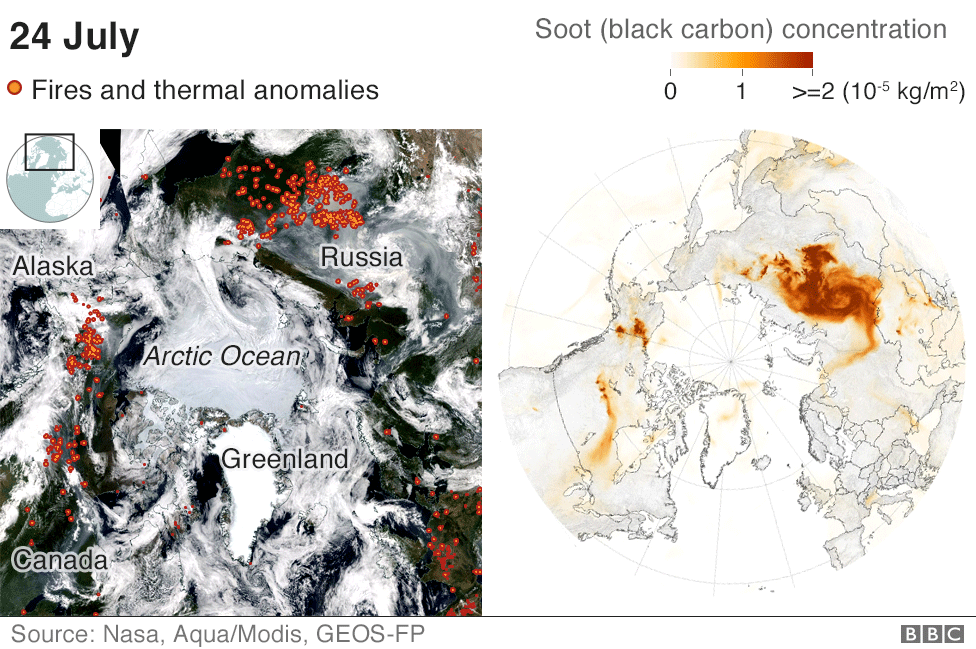

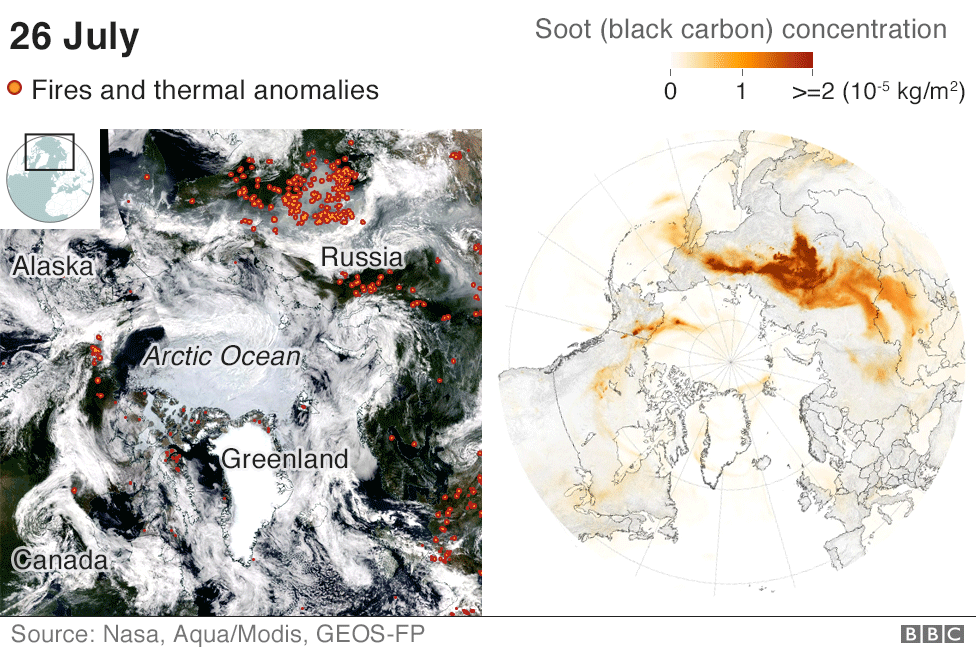

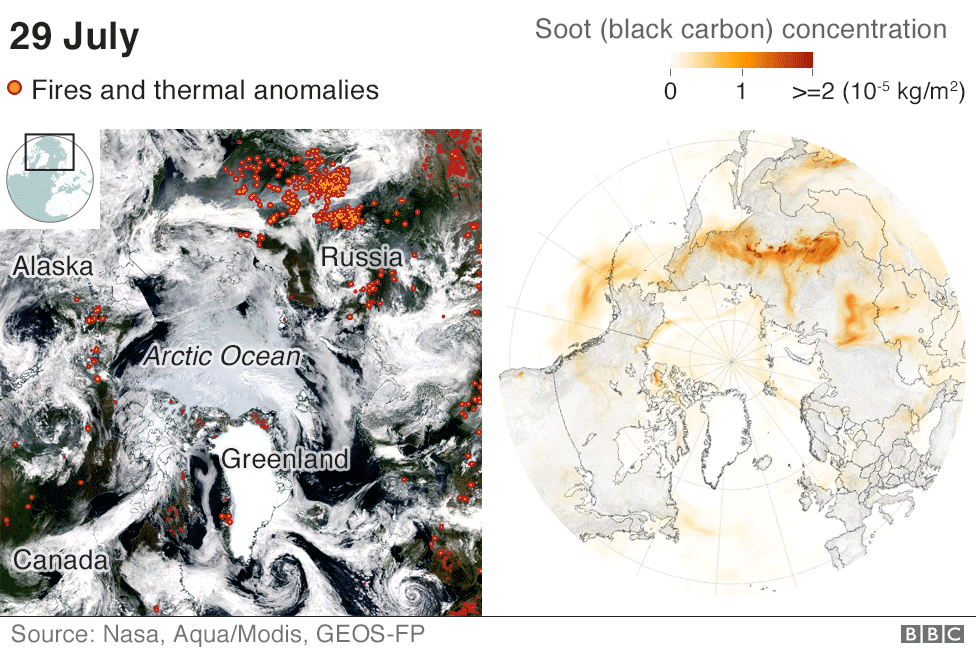

The satellite images on the left below show the fires as red dots. The globe on the right shows the concentration of black carbon particles - or soot - released by the fires.

This soot can be harmful to humans and animals, entering the lungs and bloodstream.

It also plays a role in global warming. Nasa scientists say the soot absorbs sunlight and warms the atmosphere. If it falls on ice or snow, it reduces reflectivity and can trap more heat, speeding up the melting process.

The fires also contribute to the climate crisis by releasing carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere.

They emitted an estimated 100 megatons of CO2 between 1 June and 21 July, almost the equivalent of the carbon output of Belgium in 2017, according to Cams.

How unusual is this?

Although wildfires are common in the northern hemisphere between May and October, the location and intensity of these fires as well as the length of time they have been burning, has been particularly unusual, external, according to Cams.

"It is unusual to see fires of this scale and duration at such high latitudes in June," said Mr Parrington.

"But temperatures in the Arctic have been increasing at a much faster rate than the global average, and warmer conditions encourage fires to grow and persist once they have been ignited."

Extremely dry ground and hotter than average temperatures, combined with heat lightning and strong winds, have caused the fires to spread aggressively.

The burning has been sustained by the forest ground, which consists of exposed, thawed, dried peat - a substance with high carbon content.

Global satellites are now tracking a swathe of new and ongoing wildfires within the Arctic Circle. The conditions were laid in June, the hottest June for the planet yet observed in the instrumented era.

The fires are releasing copious volumes of previously stored carbon dioxide and methane - carbon stocks that have in some cases been held in the ground for thousands of years.

Scientists say what we're seeing is evidence of the kind of feedbacks we should expect in a warmer world, where increased concentrations of greenhouse gases drive more warming, which then begets the conditions that release yet more carbon into the atmosphere.

A lot of the particulate matter from these fires will eventually come to settle on ice surfaces further north, darkening them and thus accelerating melting.

It's all part of a process of amplification.

What is being done to tackle the fires?

Russian President Vladimir Putin has ordered the army to help tackle the fires raging in Siberia and other regions in the east.

A state of emergency has been declared in parts of the republics of Buryatia and Sakha (Yakutia). Ten planes and 10 helicopters with firefighting equipment were being deployed in the regions.

Many residents had been critical of the Russian authorities for not doing enough to tackle the fires.

Hundreds of thousands of people have signed a petition calling for tougher action after Russian authorities said they were not planning to tackle wildfires in remote uninhabited areas because they were no direct threat to people.

The hashtags #putouttheSiberianfires and #saveSiberianforests are currently trending on Twitter.

Some argue that the Notre Dame fire in Paris received far more media attention than the forest fires.

"Remember how far the news about the Notre Dame fire spread? Now is the time to do the same about the Siberian forest fires," said one tweet.

Another said: "Let's not forget that nature is no less important than history. Numerous animals have lost their homes, and many of them are probably dead. Just thinking about this is painful."

US President Donald Trump has since offered Mr Putin help in putting out the fires.

By Rosie Blunt, Dominic Bailey and Lucy Rodgers. Design by Irene de la Torre Arenas and Debie Loizou.

The BBC's Steve Rosenberg travels to the forest to see how Russians are tackling the wildfires

- Published25 July 2018

- Published21 July 2019

- Published28 June 2019

- Published24 April 2019