Danish PM apologises for historical abuse in children's homes

- Published

The prime minister addressed a room filled with dozens of victims of abuse in state-run homes

Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen has officially said sorry to hundreds of victims of historical abuse in state-run homes.

From 1945 to 1976 children were sexually abused, beaten and drugged at the homes, an official inquiry found.

The abuse took place across Denmark and campaigners have for years appealed to the state to accept it was at fault.

"The apology means everything. All we wanted was peace of mind," said one of the victims, Arne Roel Jorgensen.

The sixty-eight-year-old told the BBC how the lives of many of the children had been ruined by the abuse. Alcohol, drugs, multiple jobs and failed marriages had all taken their toll.

The Social Democrat prime minister met dozens of victims of the scandal at her official residence at Marienborg on Tuesday.

"I would like to look every one of you in the eyes and say sorry," she told them. "I can't take the blame but I can shoulder the responsibility."

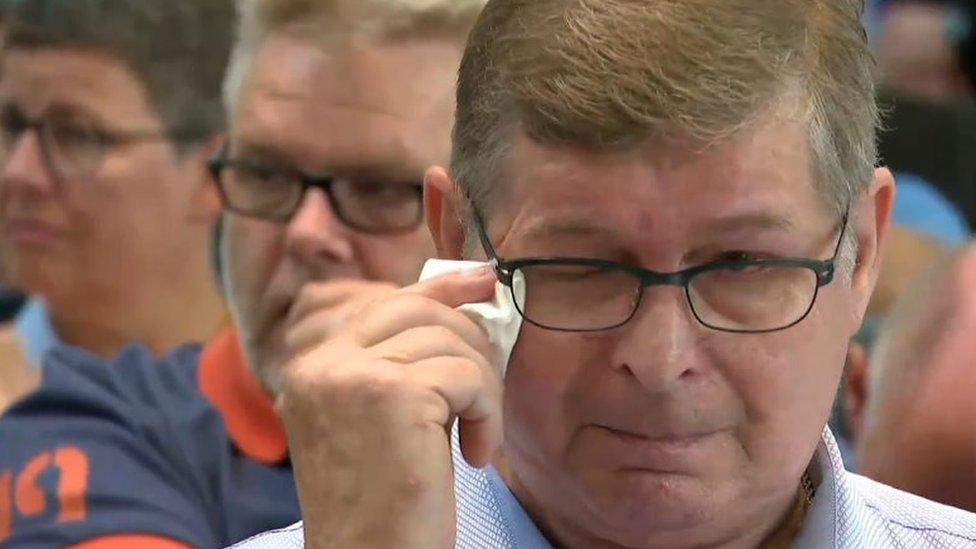

Many were in tears as she said that children had been taken from their parents and instead of getting support and warmth, they received humiliation and abuse.

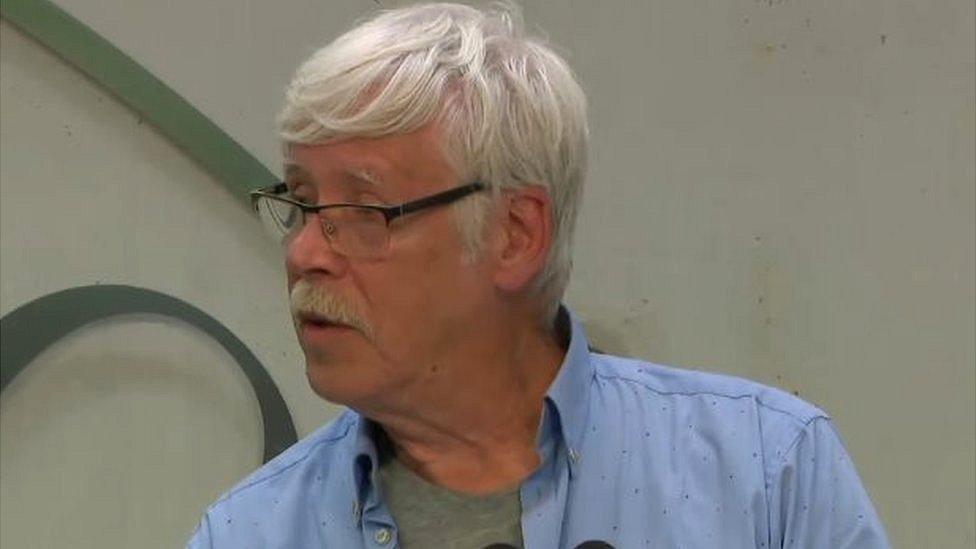

The prime minister hugged Poul-Erik Rasmussen, who campaigned for years for an apology

"The authorities did nothing. As a society, we cannot and must not close our eyes," she had said earlier.

How did the abuse come to light?

Details about the homes first hit the headlines in 2005, when a Danish TV documentary featured shocking allegations of abuse and mistreatment from victims of the state-run Godhavn Boys' Home, in north-eastern Denmark.

Emotions were high as details of what had happened in state homes were read out

The documentary also uncovered evidence that a psychiatrist had tested drugs on some of the children. Bjorn Elmquist, then an MP who had already been working on the abuse cases, said the drug LSD had been used to counter bed-wetting, leading to many of the children later becoming drug addicts.

Soon after the programme, the National Association of the Godhavn's Boys was formed and an independent inquiry was conducted in 2010.

The report, published in 2011, external, investigated allegations of abuse and neglect at 19 homes for both boys and girls, interviewing children, staff and state inspectors.

Despite its limited scope, it documented "alarming physical, sexual and psychological abuse" and researchers found blood traces on a gymnastic horse, indicating children had been beaten on it.

Mr Elmquist, now a lawyer, said many of the victims felt great shame over what had happened: "Some of them contacted me and begged me not to have their names mentioned publicly."

He spoke of boys working in fields who were punished by adults using metal tools and of the overweight master at Godhavn having his own special form of punishment. "He pushed them with his big stomach and they fell down the staircase. He put them on a sofa and sat on top of them and jumped on them," he told the BBC.

Poul-Erik Rasmussen said the state had accepted responsibility but the pain and nightmares would never leave

Arne Roel Jorgensen found out three years ago that he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder because of what had happened to him many years ago.

"Many of us have had failed marriages and we didn't learn how to act in society because nobody told us. I'm 68 now and definitely still living with the effects."

What now?

Nobody was ever prosecuted for what took place at the homes and successive governments decided the case was too old to be pursued. Before she was elected in June, Ms Frederiksen promised she would apologise for the state's role.

Mette Frederiksen became Denmark's youngest leader back in June

Poul-Erik Rasmussen, who was at Godhavn in the early 1960s, has fought for years to secure an apology and always felt that recognition was the main aim.

Many of the victims have made a point of not asking for compensation but Mr Rasmussen says he can understand anyone who wants it.

Bjorn Elmquist believes a commission and a fund should be set up to assess compensation, as he considers the abuse a clear infringement of the convention of torture that was incorporated into Danish law in 1984.

"It's not just a case of saying sorry," he says.

- Published27 June 2019