Moscow protests: Students fighting for democracy in Russia

- Published

Students are trying to raise money and hire lawyers for those still in jail

Moscow's courts have never seen anything like it - crowds of students pouring through their doors and packing their corridors.

They've been getting a crash course in Russia's legal system ever since fellow students began getting arrested at street protests.

Hundreds of young people have been detained during this summer's demonstrations, in a wave of anger after opposition candidates were barred from running for seats in 8 September elections for the Moscow city parliament.

Most of the protesters were released, fined or served short sentences. But three undergraduates are among those charged with a "riot" that even the video evidence produced by investigators does not show.

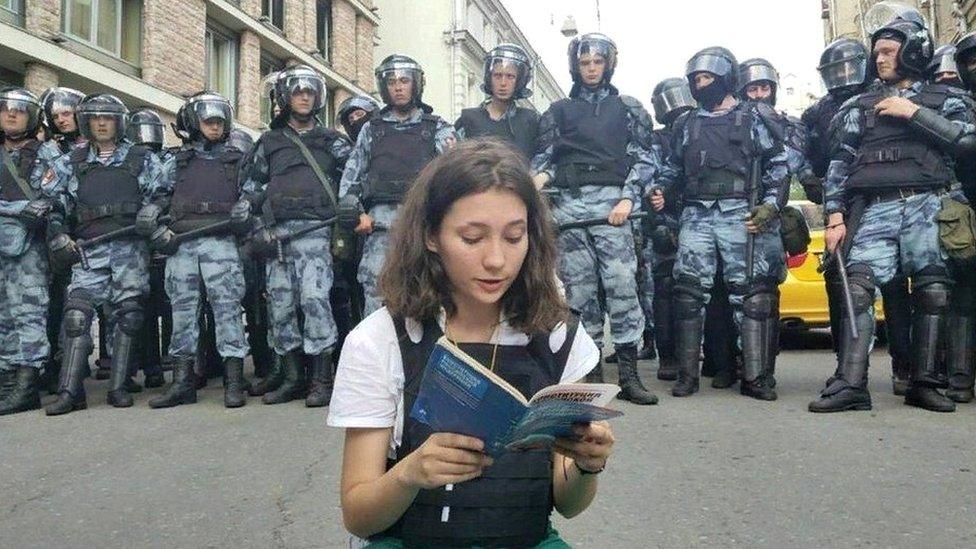

Far from frightening other students off, the tough government response to unauthorised demonstrations has swollen support for the protests.

Police officers detain a young man during an unsanctioned rally in Moscow in August

On the day of Yegor Zhukov's appeal hearing, dozens of students turned up at the court to support the 21-year-old. Their dyed hair, trainers and tattoos stood out sharply among prosecutors in high heels and bailiffs in protective vests; as did a young reporter with a Foucault paperback in her string bag.

A politics undergraduate at one of Moscow's most prestigious universities, Mr Zhukov faces up to eight years in prison for "rioting".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

His lawyer says investigators now accept that he's not the person they originally identified from video footage, encouraging protesters. But the charge against him has not been dropped.

Students set up network to fight back

Shock at what has now been dubbed the "Moscow Case" extends beyond college campuses.

Ahead of Yegor's hearing, famous artists perched on benches in the appeals court grounds signing statements vouching for his character. The popular Russian rapper Oxxxymiron was there too, offering bail money.

"I think Yegor just said a lot of things that annoyed a lot of people," the musician suggested, in a nod to the student's popular YouTube channel.

Egor Zhukov is clearly a principled, idealistic guy who didn't break any law. If he's accused of being the organiser of a riot but the riot didn't happen, that's clearly absurd

The blogger's most recent post accuses senior officials of corruption and calls President Vladimir Putin a tyrant.

"But that doesn't mean he can be imprisoned at will," Oxxxymiron said.

For many students, this summer's arrests were their first run-in with police and they had no idea how to act.

A poster at a rally in Moscow shows Russian student Yegor Zhukov, 21, behind bars

They've since developed a self-help network, run partly by the team at Russian student journal Doxa.

Used to reporting on the more mundane goings-on of university life, these days they huddle at the back of a Moscow cafe to discuss coverage of the protests and co-ordinate help for those who get arrested.

Several of those seated around the big table, with their open laptops covered in stickers, were themselves detained briefly.

The team have set up a "bot" for students to contact with questions. They help locate lawyers, deliver parcels to those in custody and crowd-fund to pay people's fines.

Doxa's own Telegram channel also contains appeals for help, like one from a first-year student asking someone to send a copy of John Locke's classic liberal text Two Treatises of Government to his detention centre.

What's behind this summer's Moscow protests?

Between mass rallies, students have also been taking it in turns to stand opposite the mayor's office holding posters denouncing the Moscow Case and "political repression".

Silent, single-person pickets are the only protests allowed in Russia without a permit, though police often arrest people in any case.

"I was a bit scared to come at first," Ilya, a physicist who read about the picket on Twitter, admits. "But I realise now it's great! So I'll be back.

This sort of single-person picket, here denouncing an arrest as a "disgrace and a crime", is the only kind of protest allowed without a permit

"It's bad that an election campaign has turned into prosecution and criminal cases. It shouldn't be like this," he added.

How student's court defiance spread

Only a handful of students actually made it into the courtroom for Yegor Zhukov's appeal hearing.

He himself joined the court on a video-link from his remand centre, standing to address the judge courteously as "Your Honour". But when the moment came for his final speech, the student sounded like he was recording his blog.

He congratulated the authorities for increasing support for the opposition by their actions.

![People take part in a rally in support of rejected independent candidates in the Moscow City Duma [Moscow parliament] election, in central Moscow, Russia, 10 August 2019](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/976/cpsprodpb/33A4/production/_108502231_gettyimages-1160650420.jpg)

An estimated 60,000 people rallied in Moscow on 10 August in what was described as the biggest opposition rally since 2011

"I can say with certainty that Russia is striving inevitably towards freedom," he said, concluding: "I don't know whether I will be freed, but Russia certainly will be."

His defiance spread quickly through the young crowd outside, glued to their phones.

"This speech was great, kind of inspirational," politics student Mstislav said. "It will be all over social media."

He described friends live-streaming their arrest from inside police vans or posting photos from custody as "the new normal", explaining that it was viral videos of police brutality against protesters that had brought him out in protest for the first time in his life.

Russian couple face losing their children after footage of their baby was posted online

"We've crossed the line when we were scared," the 21 year old said. "Now we're just angry."

Another student, Alexander, called it a "speech with sparks".

"Being in prison isn't completely negative, you get so many new people who want to know you!" the science undergraduate added, noting that Egor Zhukov had accumulated several thousand more subscribers to his blog since his arrest.

So, like many others, Alexander said that the student's arrest would not stop him protesting.

"The older you get, the less you want to change something. You think, 'My job, my 100,000 roubles. How I can protest?'" he argued, bright red headphones looped around his neck.

"But young people have nearly nothing to lose," Alexander explained. "They will live in this country, not for 20 years, but 100. And they want to live that 100 in a good country."

- Published10 August 2019

- Published7 August 2019

- Published3 August 2019

- Published3 August 2019