Stasi files: German plan to transfer files sparks concern

- Published

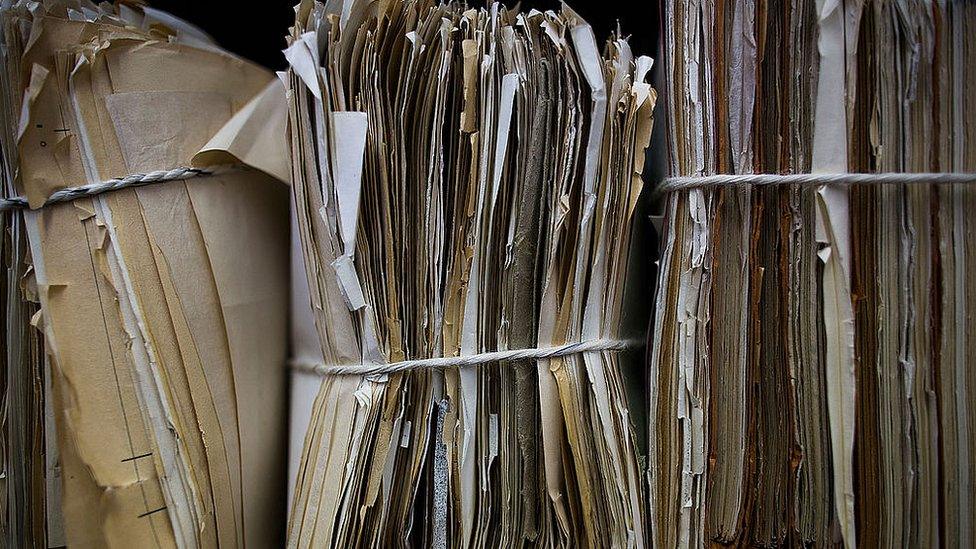

Millions of Stasi documents have been collected and preserved

Germany's parliament has voted to transfer the secret files of the Stasi, the intelligence service in communist East Germany, to the national archives despite concerns from researchers.

Millions of files compiled on suspect citizens during the Cold War have been managed independently since the communist state collapsed.

Officials says the files will be better preserved and still be accessible.

But critics warn that "a lid will be put on history".

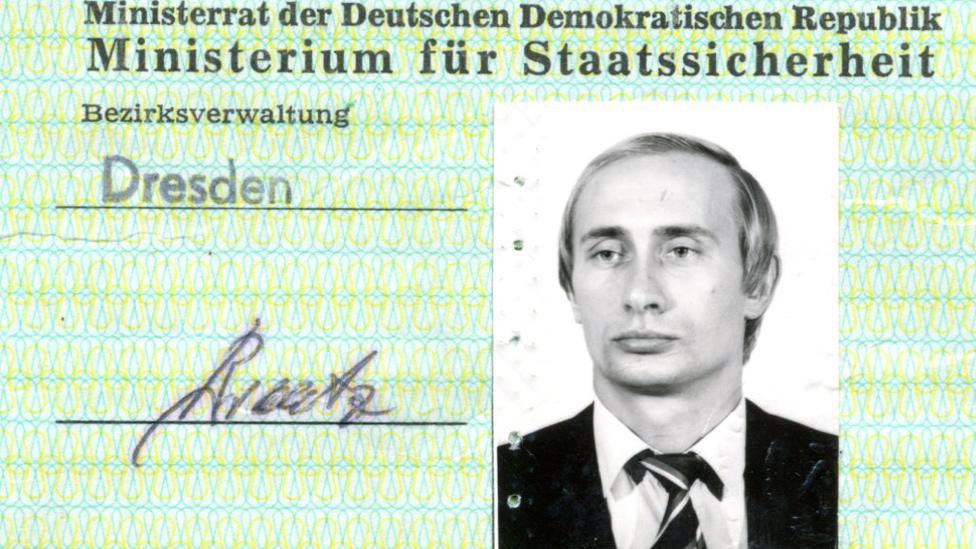

The Stasi, short for Staatssicherheit (state security), was notorious for its surveillance of East Germany's citizens, many of whom were pressed into spying on each other.

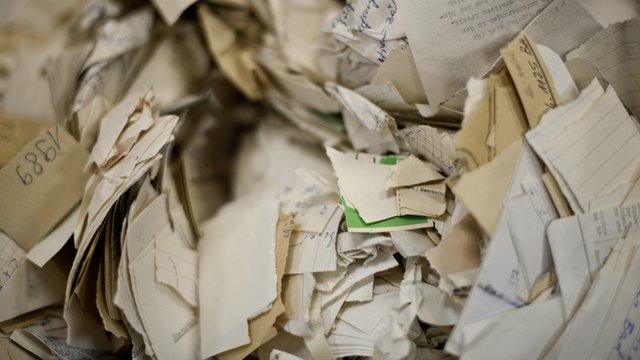

After the Soviet-supported state collapsed in 1989, Stasi officers tried to destroy records - at first using shredders and then desperately tearing documents up by hand.

The Stasi's offices were stormed by groups of "citizen committees" who seized all that was left of the documents to preserve them for future generations.

Bags of torn up documents from the Stasi files are kept and could one day be pieced together

Since then, thousands of former East German residents have been able to read what the secret police knew about their lives - and which of their friends, family and colleagues had informed on them.

Following the vote in parliament, federal commissioner for the records Roland Jahn said that millions of documents could now be better preserved and digitised. At the moment only 2% of the archive is recorded digitally.

He also promised that the files would still be accessible to historians, journalists and former victims of the Stasi.

He said he aimed to make the documents "fit for the future as we can tap the expertise, technology and resources under the roof of the Federal Archives".

Many former citizens of East Germany have been able to check on what the secret police knew about them

"We are sending the message that on the 30th anniversary [of the fall of East Germany in 1989] we have this symbol of the peaceful revolution - that is, the access to the files and the possibility to use them - and that is something that we are securing permanently," he told broadcaster Deutschlandfunk.

However, critics fear that under federal control the archive will be less accessible and that the move is an attempt to draw a line under the communist regime.

One support group for former Stasi victims said it feared the oversight of the files could be subject to political whims and that potentially embarrassing information could be hushed up.

Werner Schulz, a former regime critic and now a member of the Greens party in the European Parliament, said he feared that "a lid will be put on history".

Historian Hubertus Knabe also cautioned that Stasi files authority - the largest institution for dealing with East Germany's past - would no longer exist after 2021 when the transfer takes place.

"The signal being sent to many victims of the East German secret services is that the political establishment wants to draw a line under it," he told Bild newspaper.

- Published11 December 2018

- Published14 September 2012

- Published6 September 2013