Climate strikes: Why Russians don't get Greta's message

- Published

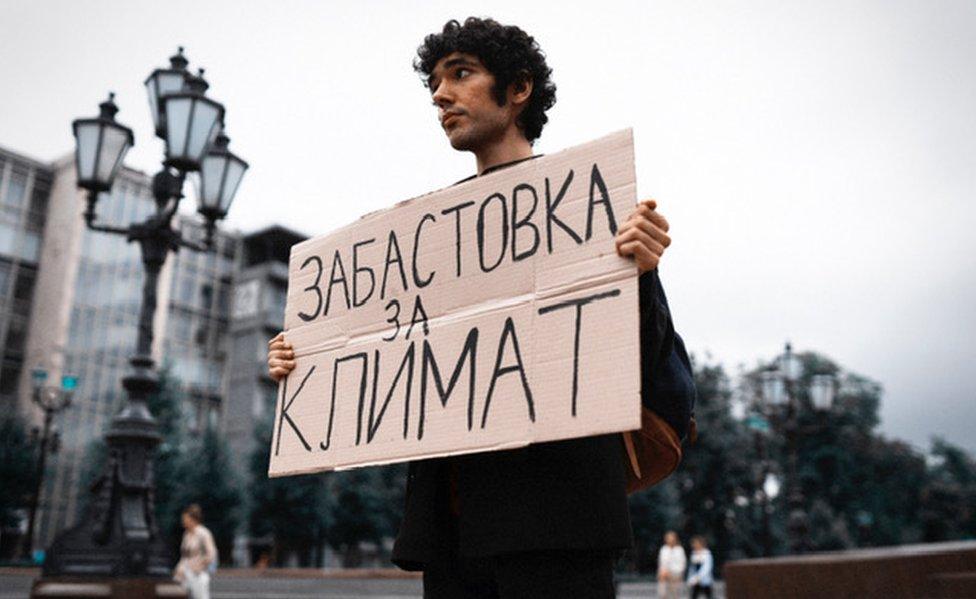

Arshak Makichyan holds a sign reading "climate strike", but his solitary Fridays for Future protests generate little enthusiasm in Moscow

For 30 Fridays on the trot, a young Russian violinist has stood in central Moscow in a one-person protest.

Arshak Makichyan is not picketing about free elections, police violence or political prisoners. His big concern is the planet and his inspiration is Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg.

"This is about our future," the 24-year-old explains, echoing the teenage campaigner. He says he began to read about climate change after seeing her protests, and realised the threat.

"Russia is the world's fourth biggest emitter of greenhouse gases and our government won't act without pressure. So it's important to strike for the climate."

But it seems many Russians have a problem with Greta.

'A kind and very sincere girl'

Presenters and commentators on state TV channels have mocked the climate activist relentlessly, even cruelly.

Putin on Greta Thunberg: "I don't share everyone's enthusiasm"

Social media users have insulted her and this week President Vladimir Putin patronised the teenager, suggesting someone should "explain" just how the adult world works. "I'm sure Greta is a kind and very sincere girl," he added.

There's a lot of talk of mysterious forces "controlling" her and column inches asking the eternal Russian question "who benefits" from her activism.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

It is possible they just don't get it.

Environmental activism is not big in Russia, where many feel they have more pressing things to fret about. High prices, poverty and corruption all regularly top the lists of concerns, way above climate change.

Then there's the fact that politicians often hail the economic benefits of global warming: opening up the Northern Sea Route, for example, for both shipping and energy exploration in the Arctic.

"You are failing us" - Greta tells world leaders

Russia is a major fossil fuel exporter, of course.

And the idea of getting warmer is unlikely to worry people too much - not in a country where for half of the year your nostril hairs freeze as soon as you step into the street.

Are Russians waking up to climate change?

Many would struggle to do much to help halt climate change, even if they did care.

In most homes you have to open a window in winter to regulate the heating because radiators are turned on centrally, full blast.

Recycling does now exist in some places and it's improving. But it's still haphazard at best and voluntary. As one colleague once explained, memorably: "In Russia, we have lots of trees."

But as of this summer, there are a lot fewer of them.

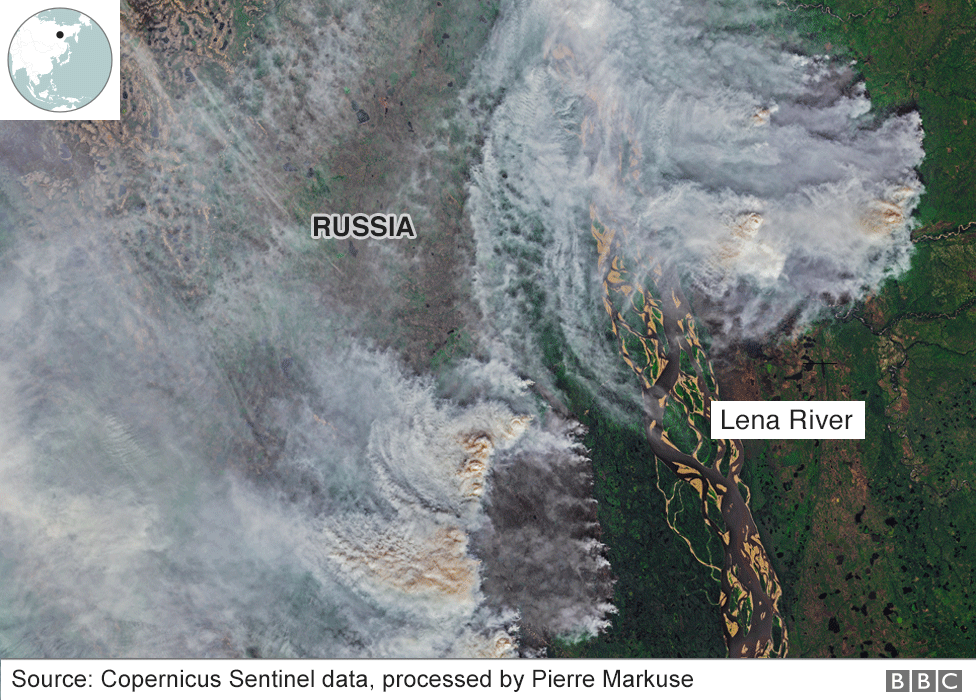

Wildfires swept forests in Siberia and far eastern regions this year on an unprecedented scale. Those, and mass floods, were blamed on climate change.

A satellite image shows wildfires in Siberia during the summer

The melting permafrost has also become a more common topic of debate.

Even President Putin, who suggested Greta Thunberg consider the "reality" of developing countries' ambitions when she lectured on climate change, has expressed concern that Russia is warming 2.5 times faster than the average worldwide.

Three years after signing the Paris climate accord, the government has suddenly ratified it.

Russia seems to be waking up, belatedly, to the threat.

But climate protester Arshak Makichyan believes the harsh reaction to Greta Thunberg suggests the authorities are anxious not to be pushed into action.

"I think they're afraid the climate protests will grow here and they can't argue with the science," the young violinist says. "They're attacking Greta, because that's easier."

Last Friday's Moscow protest as part of the global climate strike was small, but not insignificant

The Friday pickets are still tiny. Some 700 people joined in at their peak, over several dozen cities.

But, to Arshak, it's all relative.

"Half a year ago, I was on my own every week," he points out. "The climate issue is new here. Before, it felt like no-one cared. So for me, a few hundred across Russia is a big deal!"

- Published3 October 2019

- Published23 September 2019