Paris killings: Terror at heart of police HQ jolts France

- Published

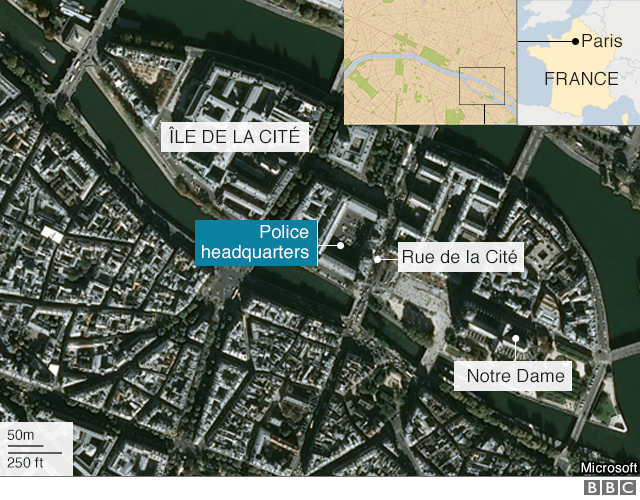

Four died at Paris police HQ when their colleague went on the rampage with a kitchen knife

The knife assault at Paris police headquarters has been described as the most serious attack in France since the Bataclan.

On Thursday 3 October, a police computer operator returned from lunch concealing a newly bought 30cm (12in) kitchen knife.

In a seven-minute spree he slashed, stabbed and killed three officers and a civilian worker - before himself being shot dead in the courtyard of the historic building.

It might seem curious to claim this as the worst since the Paris attacks of November 2015. What about the Nice lorry rampage which killed 86 in July 2016? What about the ghastly murder of elderly priest Jacques Hamel during morning Mass?

The difference, and the significance, is where it happened.

Mickaël Harpon

For the first time an attacker with apparent Islamist motivation struck from inside the system: not on the street, not in a church - but at the heart of the state apparatus.

Worse, it is now known that the perpetrator - 45-year-old Mickaël Harpon - gave out plenty of clues about his radicalisation. In 2015 he told colleagues the Charlie Hebdo attack had "served them right".

And worst of all, no-one raised the alert - even though the very department in which he worked dealt with the detection and bringing to justice of… Islamist radicals.

The French can be excused for asking: if the anti-Islamist police intelligence branch cannot even spot a potential killer, how on Earth is anyone else expected to?

Quite clearly mistakes were made or, as Interior Minister Christophe Castaner puts it, "system malfunctions".

What went wrong?

When Harpon praised the Charlie Hebdo attackers, his colleagues complained verbally to their superior but put nothing in writing - and it was quietly forgotten.

Other signals that should have been heeded were ignored. Harpon had converted to Islam in 2008 and married a Muslim in 2014, a fact that the government said should have been flagged.

The mosque he attended was frequented by a Moroccan Salafist preacher who - it is now known - was the object of an expulsion order, which was never carried out. Harpon, born in Martinique, was in contact with a group of other Caribbean-born Muslim radicals.

A local imam organised a tribute for the four victims of the Paris prefecture attack on Thursday

He had started wearing Arab-style dress to mosque, and was at times reluctant to shake the hands of women.

For a computer specialist with high-level security clearance at Paris police HQ, all this obviously merited further investigation - but it never happened.

Harpon's security clearance was granted in 2003, renewed in 2008 then again in 2013, and it was due to run until 2020. Under existing rules, tightened in 2017, renewal checks consisted of little more than reviewing the old documents. There was no interview or attempt to look into his personal life.

How could there be such negligence?

One answer may lie in the anomalous nature of the outfit for which he worked, the Paris Police Department Intelligence Directorate (DRPP).

The DRPP is heir to the famous police intelligence arm that once kept tabs on political parties, the old Renseignements Généraux (RG).

When it was disbanded a few years ago, the RG was mostly merged into the new national domestic intelligence agency the DGSI - but not in Paris.

In the capital, thanks to the historic independence of the Préfecture de Police, a separate intelligence department was allowed to persist: the DRPP.

The suspicion is that because of these turf wars the DRPP escaped some of the oversight to which other parts of the national intelligence apparatus are exposed.

Interior Minister Christophe Castaner initially suggested that Harpon had not given the "slightest reason for alarm"

But there is more to it than that.

If fellow officers suspect a colleague of dangerous tendencies, what is it that stops them making a noise?

Could fear of being accused of discrimination be a factor? Harpon was also suffering from a physical disability - partial deafness.

That is certainly the view of Thibault de Montbrial, of the Centre for Reflection on Internal Security.

"Alas, this blindness is not new," he wrote this week. "It stems from a form of self-censorship: a fear of being accused of Islamophobia and discrimination, which is encouraged by opinion-formers in the media."

Why French are wary of tip-offs

Another psychological inhibitor may be shame from the historical phenomenon known in France as la délation - or denunciation.

Since the Revolution, and before, anonymous tip-offs to authority have had a devastating effect on society. Under occupation in World War Two, there were four million put into writing!

The attack on the Paris prefecture came on a Thursday afternoon after the attacker's lunch break

The negative fall-out from this may be to make any declaration of suspicion itself suspect.

But a final consideration should be made which, while it might not exonerate those who should have spotted Harpon, does help explain their omission.

Nothing in this affair was as straightforward as it seems in retrospect. Nothing ever is.

Yes, Mickaël Harpon was behaving oddly to women. But not all the time.

Yes, he once praised the Charlie Hebdo attackers, but he also attended work functions and was seen as one of the team.

The probability is that it was not just Islamism that tipped him over the edge. He was also psychologically fragile, introverted and with feelings of inferiority linked to his disability.

As so often it was the interaction of these two elements - the psychological and the religious - that lay behind the terror.

- Published4 October 2019