Mystery of Napoleon's missing general solved in Russian discovery

- Published

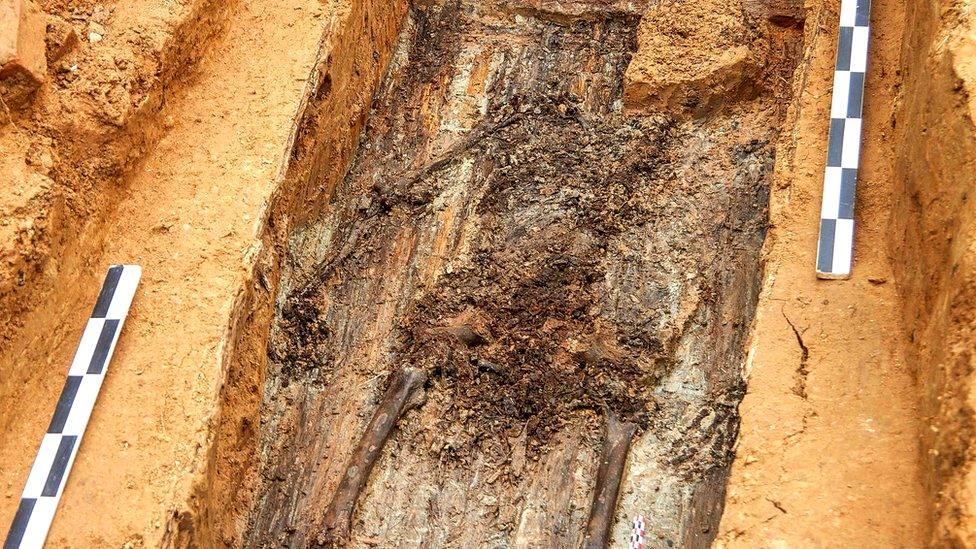

The one-legged skeleton is said to belong to a man who died aged 40-45

Napoleon's favourite general has been formally identified after DNA tests on a one-legged skeleton found under a dance floor in western Russia.

Analysis confirmed that the bones belonged to Charles-Etienne Gudin, French archaeologists say.

Gudin, aged 44, was hit by a cannonball near the city of Smolensk during the French invasion of Russia in 1812.

He had to have his leg amputated and died three days later from gangrene. His heart was taken back to France.

The skeleton was discovered in July in a wooden coffin in a park beneath building foundations by a team of French and Russian archaeologists.

What did French archaeologists say?

The search for Gudin's remains began in May and was led by Pierre Malinowski, a historian with support from the Kremlin.

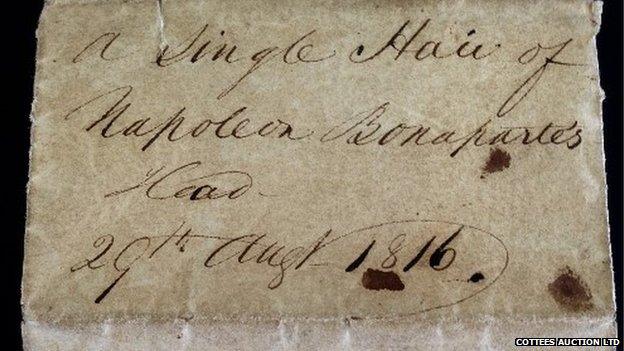

This week he said that DNA tests from the remains found in Russia matched those of Pierre-César Gudin, Charles-Etienne Gudin's brother and also a Napoleonic general.

"The DNA fits 100%," Mr Malinowski told France's France Bleu broadcaster. "There is no longer any doubt."

Archaeologists at a site of Gudin's supposed burial place in Smolensk, Russia

At the time of his death on 22 August 1812, the French army removed Gudin's heart and buried it in a chapel in Paris' Père Lachaise cemetery.

Researchers used the memoirs of Louis-Nicolas Davout, another French general of the Napoleonic era, who organised Gudin's funeral and described the location. They then followed another witness account, which directed them to the coffin.

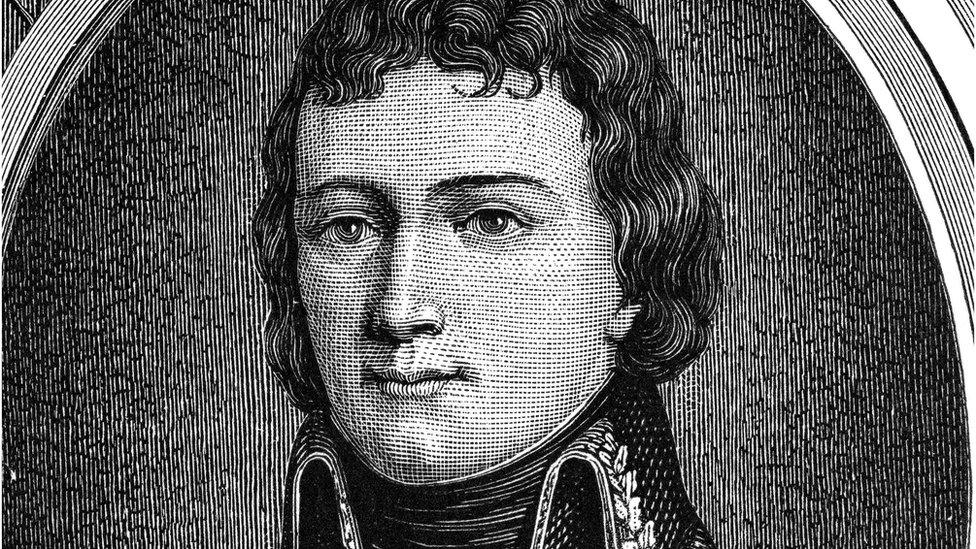

Who was General Gudin?

An aristocrat by birth, Gudin was a veteran of both the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars.

He attended the same military school as Napoleon Bonaparte, and is believed to have been one of the French emperor's favourite generals.

Charles-Etienne Gudin died after being hit by a cannonball more than 200 years ago

A bust of his likeness resides in the Palace of Versailles, his name is inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe monument in Paris and he also has a street in the French capital named after him.

What about Napoleon's invasion of Russia?

The military campaign ended in a disastrous retreat from Moscow in 1812.

Napoleon's Grande Armée (Great Army) of 400,000 men was thought to be unbeatable and he himself had anticipated a rapid victory.

But having initially captured Moscow after the Russian army withdrew during a harsh winter, the emperor then realised he too had to turn back.

In a letter in which he vowed to blow up the Kremlin, Napoleon exposed his frustration at the campaign, with his army ravaged by disease, cold and hunger: "My cavalry is in tatters, a lot of horses are dying."

- Published3 January 2019

- Published17 July 2019

- Published9 June 2015

- Published2 December 2012