Switzerland's plan to stop stockpiling coffee proves hard to swallow

- Published

Switzerland stockpiles 15,000 tonnes of coffee - enough to last three months in an emergency

The Swiss are nothing if not well-prepared. Theirs is a country with a nuclear bunker for every household, a country that tests its air raid sirens every year, and a country that, although one of the wealthiest in the world, stockpiles thousands of tonnes of goods in case of an emergency - including coffee.

But when the Swiss government proposed ending the stockpiling of coffee earlier this year, the plan was met with fierce resistance.

The drink, low in calories and with little nutritional value, did not belong, the government said, on the "essential to life" list.

But this led to a public outcry. The Swiss are among the world's biggest drinkers of coffee, and many, it seems, do regard it as "essential". Faced with such a public response, the government said it would reconsider.

The 15,000-tonne supply of coffee, which is enough to last the Swiss population of 8.5 million for three months, is part of an essential list of goods that includes sugar, flour, cooking oil and rice, as well as fuel, fresh water, and medicines.

Why have a stockpile anyway?

Landlocked Switzerland produces only half the food it needs, and severe shortages during both world wars encouraged successive governments to build up stockpiles in order to support the population in case of an emergency.

Producers of goods on the essential list are required by law to store a certain amount, and the government pays them for the cost of storage.

Private citizens are also expected to stock emergency supplies: among them drinking water, food for a week, a torch, and toilet paper. As recently as 2016 the government issued a video (in German) detailing how best to prepare for a "catastrophe or emergency", external.

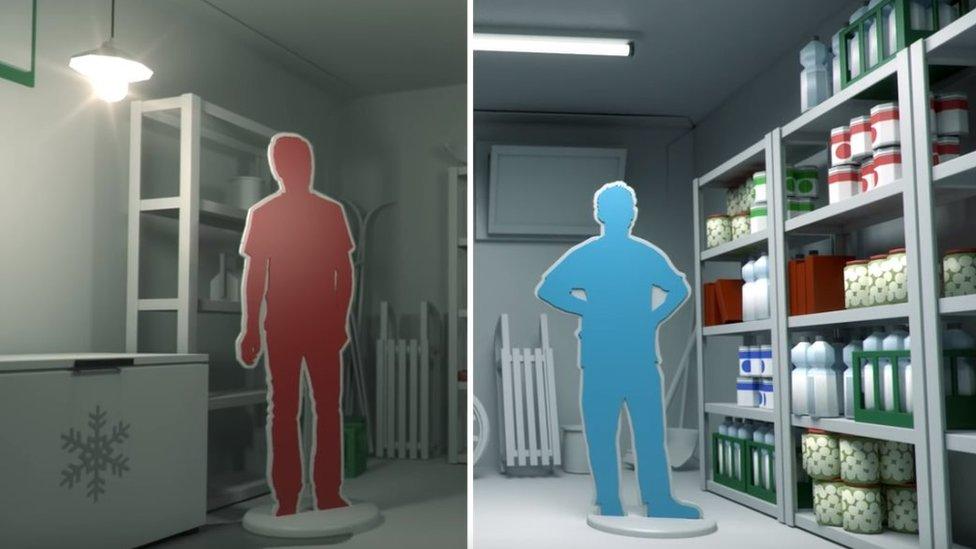

Tim the unready (L) is contrasted with Tom the ready, in this government video

The video features two men - "Tom the ready" and "Tim the unready" - at opposite ends of the scale: Tom's cellar is well stocked, Tim has nothing to feed his family when disaster strikes.

In fact, the latest statistics show that only a third of Swiss citizens bother with a personal stockpile these days.

A quick and unscientific survey around the cafes of Bern elicits laughter and comments such as "no, but my grandmother stockpiled pasta", "I don't have the space, my flat is too small" or "no, the only things in my cellar are my skis".

So why is coffee sacrosanct?

It appears, however, that the Swiss do expect their government to store items for them - and that includes coffee.

Switzerland consumes a staggering 8kg (17.6lb) of coffee per person per year. It's rare to find a Swiss person who does not drink it: a milky coffee in the morning and a nice little espresso or ristretto after lunch and dinner are rituals of daily life in the country.

Not having that fix, even for a week or so, seems unimaginable.

And so the government, taken aback by the storm of protest - and probably also encouraged by Swiss coffee producers who may not want to lose that generous storage fee - is rowing back on its decision.

Not such a silly idea then?

Switzerland's Federal Office for National Economic Supply is using the unexpected attention to remind people that stockpiles are not a completely crazy idea, external, even if other, less diligent, countries may have abandoned them.

Large-scale wars on Switzerland's borders may not be likely any time soon but, the office says, governments and citizens should still prepare for natural disasters, cyber attacks that could knock out supply chains and shortages caused by global economic crises.

Coffee giant Nestlé, in common with all Swiss importers and retailers, are required by law to store coffee beans

Switzerland's stockpiles have actually come in for good use quite recently. Last year, the level of the River Rhine fell so low that ships carrying mineral oils and fertiliser could not get to Switzerland, and the stockpiles came in handy.

Also, during a global shortage of antibiotics in 2017, Swiss hospitals dodged a crisis because the required drugs had been stored.

So it is likely that the Swiss government will be hanging on to its stockpiles, with the full support of its citizens… as long as coffee remains on the list.

You might also be interested in:

Why Italians are saying 'No' to takeaway coffee

- Published11 April 2019

- Published22 November 2018

- Published19 June 2023