General election 2019: Politicians risk heckles in rain-soaked campaign

- Published

On the campaign trail: Boris Johnson of the Conservatives, Labour's Jeremy Corbyn and Jo Swinson of the Liberal Democrats

Despite many politicians, political commentators, analysts and journalists including me saying this is one of the most important elections since World War Two, one can't help feeling it just hasn't caught fire yet.

It could be because the weather's been rubbish, because people aren't inspired by the choices, or perhaps because there are still four weeks to go to the 12 December general election. Whatever the reason, this campaign has yet to burst into life.

None of which is to say lots hasn't been happening. Candidates have been knocking on doors, party leaders touring the country and millions of people receiving targeted political ads via Facebook and other social media.

Farage gives Johnson benefit of the doubt

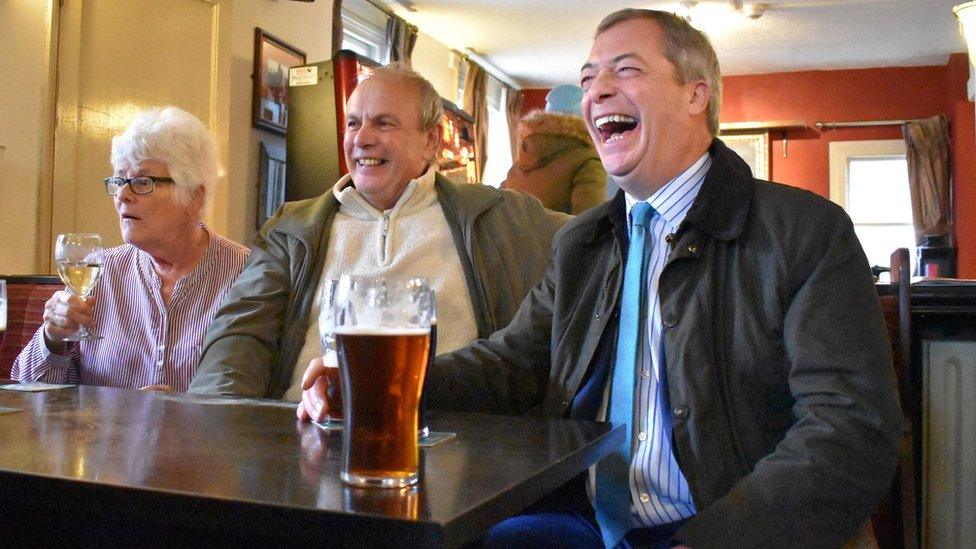

The stand-out moment of the week has to be the decision of Nigel Farage, leader of the Brexit Party and the man who can claim much credit for there ever having been a referendum in 2016, deciding not to run candidates against sitting Conservative MPs.

Nigel Farage's decision not to run candidates in Conservative-held constituencies was the big development of the campaign week

Why? Because he's trusting that Boris Johnson will deliver Brexit, and a pretty hard one at that, if Mr Johnson wins the election. And because he's come under an awful lot of pressure from enthusiastic Brexiteers saying he now poses the biggest threat to Britain ever leaving the EU by splitting the Leave vote between his party and the Conservatives.

For Mr Johnson and the Conservatives it is surely an early Christmas present from Mr Farage.

Yes, they would have preferred, no doubt, that Mr Farage had announced he was going on holiday until at least 15 December and would not stand any Brexit Party candidates at all. But it does mean the Conservatives are under far less pressure in terms of the seats they already hold, and can therefore concentrate more of their money and effort on trying to win new ones from other parties.

Risks of the road

I mentioned earlier the digital nature of modern campaigning, but political leaders still like to be seen out and about, meeting "ordinary people".

This week we were reminded why that is always a risky as well as rewarding undertaking.

Just as campaigns always have their gaffes, they also have their heckles.

While visiting some of the many people affected by flooding in the North of England, a wellington-booted Boris Johnson waded through water hoping to show sympathy with beleaguered residents.

Inevitably, one fed-up lady pushing a wheelbarrow was approached by the prime minister and expressed her unhappiness, all in front of camera- and mobile phone-wielding travelling journalists.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

"I'm not very happy about talking to you," she told Mr Johnson. "So if you don't mind I'll just mooch on with what I'm doing because you've not helped us. I don't want you to meet us." Ouch.

The leader of the opposition Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn, didn't fare much better.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

On the campaign trail in Scotland he encountered a man, who turned out to be a minister in the Church of Scotland, who heckled him thus: "Do you think the man who's going to be prime minister should be a terrorist sympathiser, Mr Corbyn? Who's going to be the first terrorist invited to the House of Commons when you're prime minister?"

So what, you might say. But video snippets of both encounters were very widely shared indeed.

Read more on the election campaign:

Are the campaigns having an effect?

The main parties stuck pretty doggedly to their campaign themes: the Conservatives to get Brexit done; Labour to end austerity; Liberal Democrats to stop Brexit; Scottish nationalists to hold another referendum on independence, and so on through the other parties too.

Scottish National Party leader Nicola Sturgeon stressed her party's priority was a second referendum on independence for Scotland

Interestingly, despite all this whirl of activity, the opinion polls have barely shifted a fraction.

Boris Johnson had an average lead in the opinion polls of 10% at the start of the campaign and now has one of 10.7%!

View from Northern Ireland

I spent the week viewing the campaign on the road in Belfast.

General election 2019: Do parties still matter?

Contrary to what some might expect, given its past history of conflict, Belfast is, as it was even during the Troubles, an immensely warm and friendly city.

But there is clearly a mood of uncertainty and anxiety here.

Uncertainty over what the result of the election might mean in terms of Brexit.

Anxiety over the existential question back in focus thanks to Brexit: namely what is Northern Ireland's medium to long-term future. Is it to continue to be a part of the UK, or become part of a united Ireland?

Those I spoke to were nervous that this sensitive and difficult question was being asked again, but hopeful that somehow Northern Ireland could avoid any return to violence while searching for answers.

- Published11 December 2019