Gilets Jaunes: Anger of yellow vests still grips France a year on

- Published

A yellow vest anti-government march in Toulouse in May

Yellow vest protesters from across France are staging protests in Paris to mark the first anniversary of their grassroots movement.

Several people have been arrested, police have fired tear gas to disperse some demonstrators, and an attempt to block the main ring-road in the city was repelled. In one area, demonstrators set fire to wooden pallets.

The weekly demonstrations that brought parts of France to a standstill at the end of last year have shrunk to a few small groups, turning out each Saturday to press their demands.

But three-quarters of French people surveyed by pollsters Odoxa in October said they thought the movement, known in French as the Gilets Jaunes, was not yet over.

At a roundabout near Reims last week, a few dozen protesters in yellow vests cooked sausages over a small fire. The question running through many of the conversations here was: what next?

"I don't know how long it'll last," said Stéphanie Logrieco. "Will we finally give up? I don't know. But, in any case, what we have done so far is beautiful. We gathered the crowds and awakened consciences, and I'm happy about that."

Protests still galvanising France

Stéphanie was planning to be in Paris on Saturday for the anniversary protest. But that's not the most important date.

Like many people, she is looking ahead to 5 December, when France's railway unions have asked hospital workers, teachers, security forces and students to join them in a large-scale strike.

The government's fear is that these traditional groups could join up with the yellow vests in a major conflagration of protest. And many yellow vests say they are planning to take part.

"I'm a civil servant, and this is the first time in my life I'm going on strike," Stéphanie explained. "In the beginning, we were a little detached from the unions, but I think it's important to stand together."

Last December yellow vest protesters put up barricades in central Paris

One of the core traits of the yellow vest network during its early stages was a rejection of any kind of organised leadership. Offers of support and alliances from both unions and political parties were routinely rebuffed.

Those who tried to play leadership roles within the movement itself were often fiercely attacked.

But now, as the movement has fractured over how to proceed, and several founding members have put themselves forward as political candidates in next year's local elections, has something changed?

"We have no choice," said Didier Thomas, another of the protesters out for the roadside barbecue in Reims. "If we don't join the unions, we won't be able to do anything."

France fuel protests: Who are the people in the yellow vests?

Prof Yves Sintomer, a political scientist at Paris 8 University, says the movement has shrunk from its early days as a mass protest, but believes if the unions and yellow vests join up next month it could surge again.

"You would have the forces of the organised Left [together with] the forces of this non-political, non-organised mobilised working class, or civil society - and the danger for [Emmanuel] Macron would be that he ends his presidency with no capacity to act."

In his eyes the yellow vest movement has been good for democracy in France.

"There's a danger in France of reducing democracy to a small political game, where only those who want to be elected are playing, and the people are watching," he told me. "The gilets jaunes have again put this huge majority of people at the front of the stage."

Unfinished business

This leaderless protest movement has already proved to be the toughest challenge to President Macron's reformist goals.

In order to stop the growing anger among protesters, and widespread sympathy among French voters more generally, he was forced to row back on the fuel tax rises that triggered the movement, and offer additional measures including a cut to pension tax and a rise in the minimum wage.

But many yellow vest members say it's not enough.

"Despite everything, [France] continued in the same direction, with the increase of tariffs," said protester François Montagnac.

"On the question of purchasing power, there's nothing. On the question of democracy, there's nothing about giving us more referendums or anything. And on pensions, we're told we'll have to work longer."

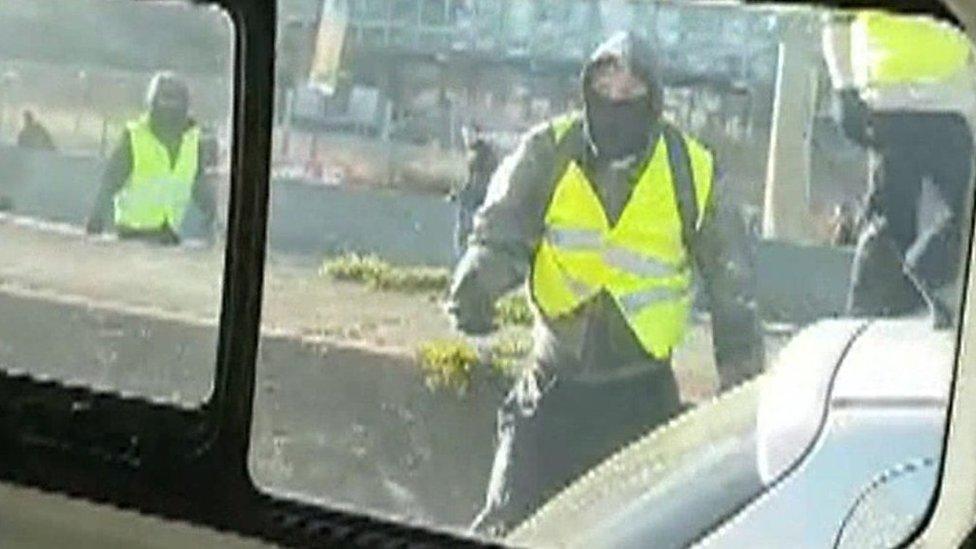

'Yellow-vests' pelt police van with stones

President Macron has admitted that he plans to continue with his reformist agenda. The next wave of controversial reforms - tackling France's complex pension system - is the spark for December's strike by the unions.

Some fear another round of clashes could bring a repeat of the violence seen last year, when rioters and radical groups joined the yellow vest protests. Security forces have been criticised by some for their handling of the demonstrations, as injuries among both police and civilians mounted.

Some recent surveys suggest that a majority of French don't want the yellow vests to mobilise again, even if they sympathise with their aims.

But even without changing the government's operation or agenda, the yellow vests have achieved a different political effect: a group of people who say they used to feel invisible have found a way to make their voices heard.

"For me personally, nothing much has changed," Stéphanie said. "But it was a great human adventure. We rediscovered generosity, solidarity; people woke up. We found a real family."

- Published21 September 2019

- Published6 December 2018

- Published1 December 2018

- Published18 February 2019