How fast could UK-EU trade deal be struck?

- Published

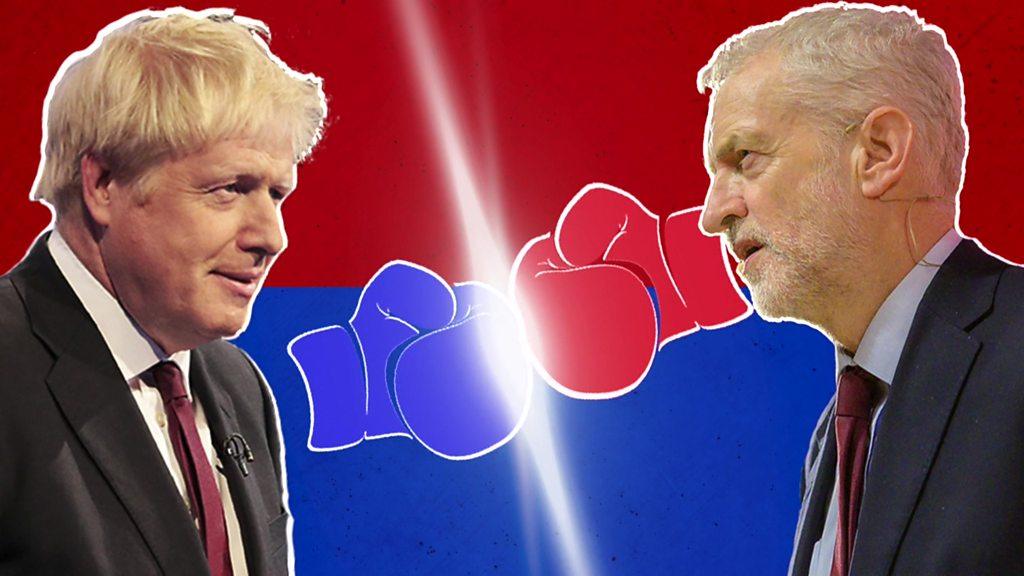

Brussels fears that whether Corbyn or the Johnson form a government, 2020 could well be another year of uncertainty

"Not in my wildest dreams would I imagine that a possibility!"

This is how an influential European diplomat responded when I put to him Boris Johnson's assertion that a trade deal with the EU could/would/should be completed by December next year.

In these times of distrust in the media, charged emotions over Brexit and in the lead-up to a general election, I appreciate that many readers dislike journalists referring to unnamed sources, such as this "influential diplomat".

But people speak to me on condition of anonymity. That's how I get good background information and - in the case of the Conservative Party's speedy trade deal pledge - I can assure you that this diplomat's response was one of the politer ones I've comes across, off the record, in EU circles.

European politicians dismiss Boris Johnson's claim that he will "get Brexit done" if he wins the election. In fact, Brussels fears that whether Labour or the Conservatives form a government, 2020 could well be another year of uncertainty for EU and UK businesses.

Why? Because Labour seeks to renegotiate the Brexit divorce deal and then hold a second referendum on whether to leave the EU at all, while Boris Johnson wants to take the UK out of the EU in January and is then only giving himself 11 months to negotiate a trade deal with Brussels. Meaning the threat of No Deal would loom large once again both sides of the Channel come the New Year.

Boris Johnson has vowed to "get Brexit done"

And why am I questioning Boris Johnson's ability to get a trade deal done quickly with the EU?

Even the EU's chief Brexit negotiator, Michel Barnier, and the incoming trade commissioner for the EU, Phil Hogan, have made encouraging noises. The UK is completely aligned with EU regulations right now, while still a member, so how difficult can it be to strip away layers of ties to result in a simple Free Trade Agreement (FTA)?

Truth is, Brussels is preparing to offer Boris Johnson a quick FTA should he win the election - with zero tariffs on goods - but also with the utmost levels of EU regulation bells and whistles attached (the so-called level playing field provisions). This would mean the prime minister signing up to EU environmental regulations, for example, and the bloc's state aid rules.

This is in Brussels's interest, of course. To reassure EU members that the UK won't have a huge competitive advantage over them after Brexit, but if Boris Johnson agrees to an FTA with the EU under those terms, then where is the national sovereignty he promised voters after Brexit?

My European contacts tell me the prime minister has already informed them that he can't accept being tied to EU rules like that. He will certainly try to negotiate those EU demands away. But that will take time. Which is why the EU believes, under Boris Johnson, the UK may leave the bloc in January - in legal terms.

But that practically speaking, the UK will end up still paying into the EU budget for a lot longer; still remaining a member of the customs union and the single market, with continued free movement to the UK for EU citizens - while a trade deal is negotiated. This temporary state of being out of the EU, yet still in it to all intents and purposes (though with no decision-making powers any more) is called the transition period.

Right now, Boris Johnson insists he won't extend transition beyond December next year, but the EU has seen him break his political pledges before. If he wins a majority at the polls, he could quite easily break this one. Brussels thinks he'll have to.

Another big spoke in the wheel of speedy trade negotiations with the EU is fish.

Boris Johnson promised fishermen sovereignty over UK waters after Brexit but the French, the Spanish, the Danes and the Dutch will demand fishing rights in UK waters.

If prime minister, Mr Johnson will be under pressure to relent, otherwise the EU could threaten to close their market to UK fish stocks. So where would all the UK fish be sold?

The EU could push for fishing rights in exchange for something else the UK might want in return. Conclusion: negotiations bartering is not likely to be done and dusted in a hurry.

The messiness of we'll-give-you-this-if-you-give-us-that negotiations also means it's unlikely that a sector by sector EU-UK deal could be reached, where one part of future relations (e.g. security) could be signed off, while more complicated areas are still negotiated.

Why would the UK quickly sign off on a post Brexit security deal with the EU, for example? As this is something Brussels is super-duper keen on, the UK could use security relations as a bargaining chip to get something on trade in services for example - which the UK wants but the EU is reluctant to concede.

Another complication for the UK in getting a trade deal done quickly is that it's not in Brussels' interest to make it easy, unless the UK remains tied to EU rules. Not only because Brussels wants to protect itself from a big competitor on its doorstep, as I mentioned at the start of this article. The EU is also concerned about setting precedent.

Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn locked horns over the NHS, Brexit and the Royal Family

Brussels does not want to give eurosceptics in other EU countries the impression that you can leave the bloc and its rules behind, yet still easily enjoy all the economic benefits. It also wants to avoid giving non-EU countries the impression that EU single market rules are made to be broken in trade talks.

But why would the EU cut off its nose to spite its face, you ask? Surely Brussels needs and wants good trade, security and diplomatic relations with the UK?

It does, that's true.

But as was the case in the Brexit withdrawal agreement negotiations, the EU will always put the single market first, ahead of trade and other relations with the UK. The rest of the single market is far larger and more lucrative than the opportunities the UK offers alone. Brussels is wary of harming its single market in trade negotiations with the UK.

Watch the BBC Question Time leaders' special

On BBC One and on iPlayer from 19:00-21:00 GMT

On BBC News Channel and on iPlayer 18.30-22.00 GMT, with specialist correspondents and extra spin room analysis

On the BBC News website live page

Read our guide to the Question Time special

Of course there will be give and take in the trade talks; concessions on both sides. But the EU believes - as it did during the divorce negotiations - that it is in the stronger position.

It knows Boris Johnson has promised not to extend the transition period beyond 2020. So he's under time pressure (expect a return to Michel Barnier's "the clock is ticking" pronouncements).

It knows that fishing rights and signing up to EU level playing field regulations will be politically toxic issues for the prime minister back home. Expect Brussels to want to pile on the pressure here.

The EU knows the UK will want to conclude trade deals with other countries ASAP after Brexit but those other countries will hesitate to conclude any agreement with the UK until they know what relationship it has with EU.

One other complication for the UK is that individual EU countries have different interests when it comes to a trade deal. This is also likely to slow down negotiations. For example, Spain may push for more rights over Gibraltar; I've outlined the fishing issue above.

An eventual EU-UK comprehensive trade agreement will then need to be approved by the parliament (or parliaments in the case of Belgium, for example) of every single EU member state. Each of those parliaments has a veto on the trade deal.

So while the UK focuses on its upcoming general election, with all the uncertainty it throws up, the EU is using the time and space to game-plan the various negotiation scenarios that may follow.

- Published20 November 2019

- Published28 November 2018

- Published21 November 2019