Executing a dictator: Open wounds of Romania's Christmas revolution

- Published

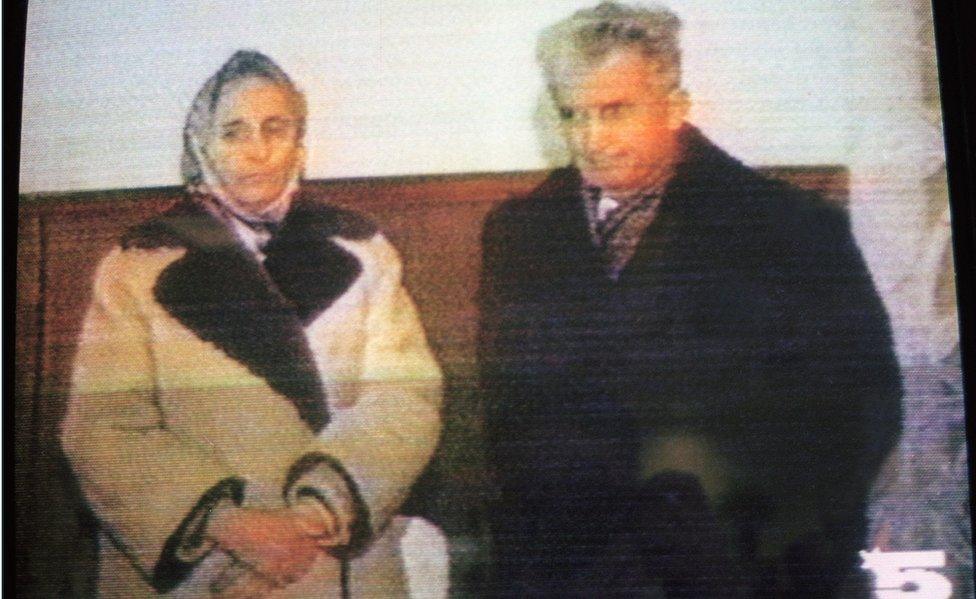

Ceaucescu and his wife Elena were found guilty by a military tribunal and executed by firing squad

It was on Christmas Day 30 years ago that Romania's tyrannical communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu was executed by firing squad after a summary trial.

A bloody battle played out in Romania in December 1989 that led to the remarkable collapse of one of Europe's most repressive communist regimes - and arguably its most menacing dictator.

For the Romanians who challenged him, it was a moment that defined their lives.

"It was war, it was a war zone here," remembers Traian Rabagia, then a 19-year-old geology student.

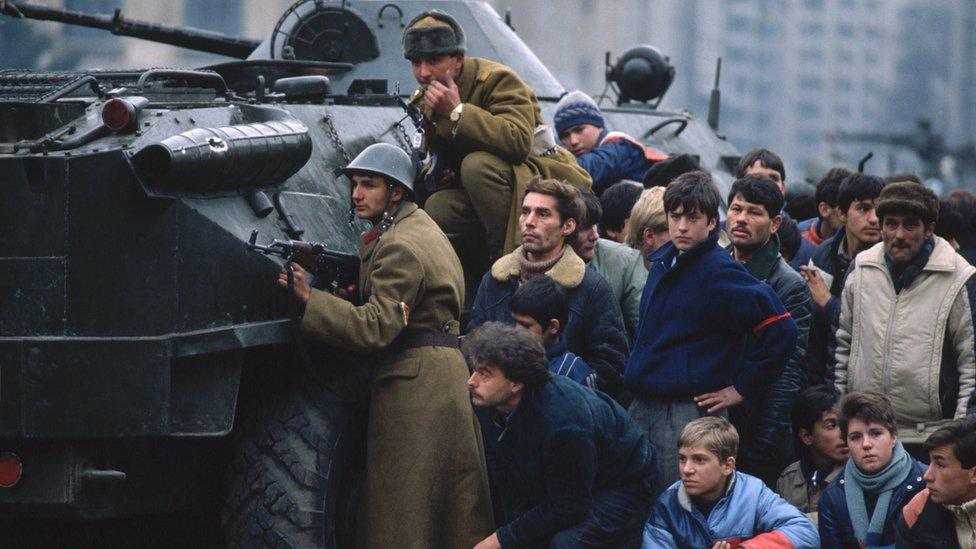

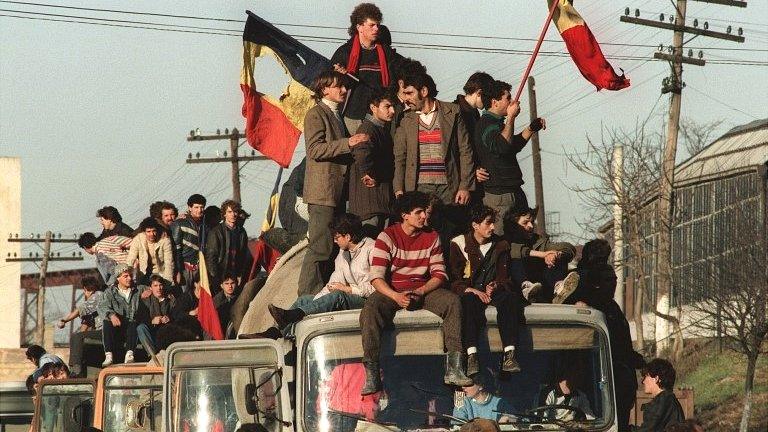

Many in the armed forces turned on Ceausescu and joined the protesters

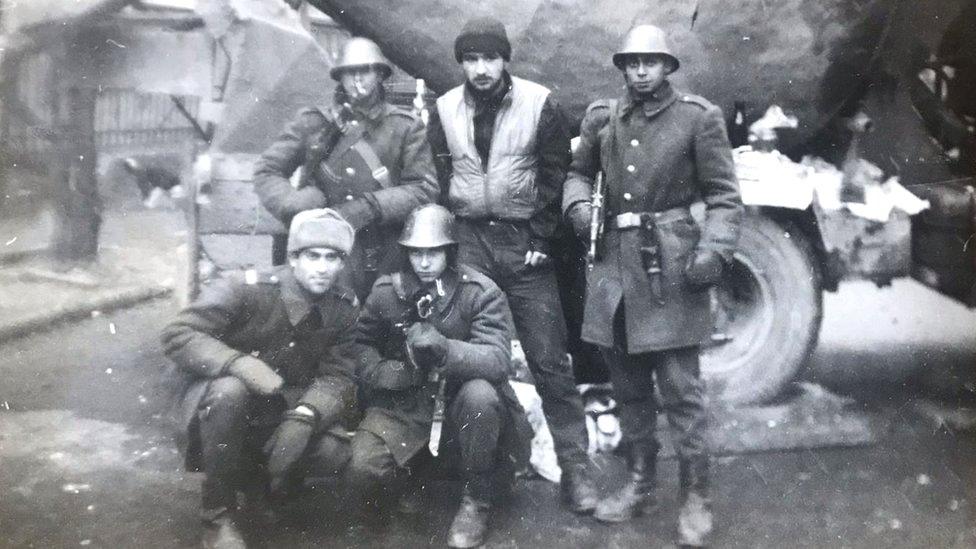

Traian Rabagia (top, centre) aged 19 with his military service colleagues in Bucharest days after Ceausescu fled

"I was shouting 'liberty!', 'we are the people!', and 'down with Ceausescu!'"

How the revolution spread

The revolt against Ceausescu's regime began in mid-December in the western city of Timisoara but was violently quashed on Ceausescu's orders.

Dissent quickly spread throughout the country, culminating in hundreds of thousands demonstrating in Bucharest, following a carefully-managed but ultimately botched speech by Ceausescu on 21 December 1989.

Moment Romanian dictator Ceausescu's execution was announced

Ceausescu had misjudged the mood of the crowd as he blamed "fascist agitators" for the Timisoara unrest; the Bucharest crowds responded by jeering and chanting "Timisoara! Timisoara!".

A visibly shocked Ceausescu attempted to appease demonstrators with promises of higher wages but dissent only grew. The national address, which was broadcast on state television in an attempt to re-establish authority, was abruptly cut from the airwaves.

On the day of Ceausescu's botched speech, Traian Rabagia joined the throngs of demonstrators who faced down pro-communist forces in the streets.

Mr Rabagia said central Bucharest in 1989 was a war zone

"There was blood all over the sidewalk there," Mr Rabagia, told the BBC, standing outside the InterContinental Hotel in central Bucharest.

A bloody revolution was under way that would end Ceausescu's 21-year despotic reign, and 42 years of communist rule in Romania.

The following day the dictator and his wife, Elena, fled Bucharest's Central Committee building by helicopter as crowds stormed party headquarters. The couple were captured 50km (30 miles) away in Targoviste.

Why Ceausescu fell

Fixated on paying off foreign debts in the 1980s, Ceausescu set about a series of austerity measures that plunged the country and its people into economic hardship.

The appalling economic situation was only exacerbated as Ceausescu splurged cash on megalomaniac projects such as the construction of the People's Palace, even today one of the largest buildings in the world.

The opulence of the Ceausescus - seen here in their dining room at the Spring Palace in Bucharest - was widely resented by Romanians

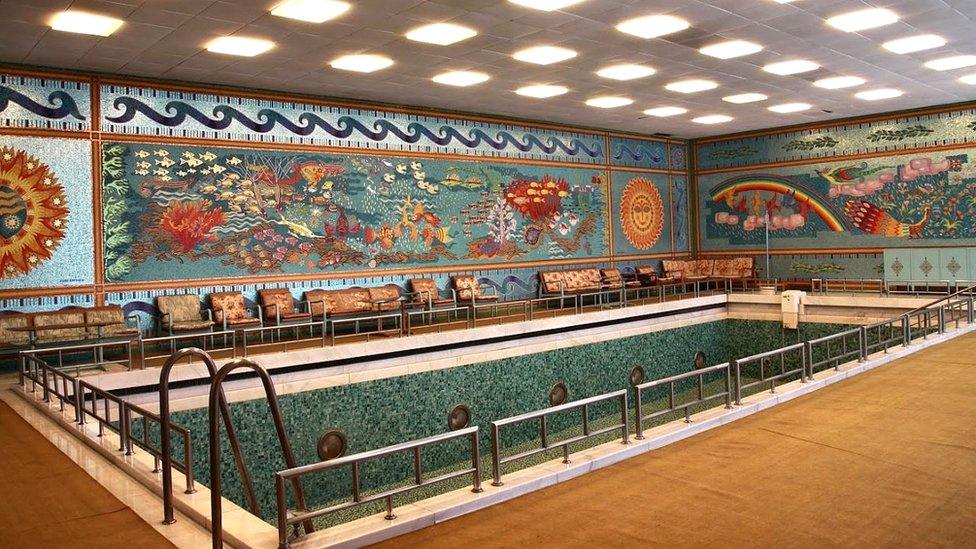

The flamboyant indoor swimming pool at the Ceausescus' Spring Palace

"I remember the poverty of the '80s, I remember in Bucharest, the breweries, restaurants, everything was dark," says Mr Rabagia.

Blighted by a lack of basics, such as food, heating, and lighting, dissent was building up in the isolationist state as Ceausescu and Elena lived in luxurious, palatial homes.

"We knew that people living in other countries had more material wealth and were living better. It was clear to me that something would happen, but nobody was really talking about it."

In the Securitate, Romania had one of the Eastern Bloc's largest and most feared secret police forces, and talking freely under the Ceausescu regime was a dangerous endeavour.

When Romanians stood up to tyranny

As many as one in four people were thought to be informers for Ceausescu's secret police in the 1980s. The Securitate were responsible for the torture and death of thousands of dissenters.

"Fear of talking was there since the early '80s," the former student remembers.

On Christmas Day, the Ceausescus were executed by firing squad, external in a show-trial that accused them of crimes against humanity.

"I felt relief. It was a good thing to do to calm people down. Wiser guys than me were saying that blood had to be spilled to settle down events like this."

Why Romanians have not put past behind them

Three decades have passed since the fall of communism and Romania is now a functioning, democratic EU country with a growing economy. But for some, scars from the bloody days of the 1989 revolution remain.

Standing outside Bucharest's Supreme Court building on a blustery late November day, 46-year-old Alexandru Catalin Giurcanu, whose father was brutally killed during the revolution, is here to seek justice.

"After 30 years our justice system is struggling to find out who killed all the people during the revolution, who the criminals are," he told the BBC.

"We are here today to start the legal process of a case that has been open since the '90s," he says.

Alexander Giurcanu (L) and Aurel Dumitrascu (R) commemorate the 1989 uprising at the Supreme Court

It was the first hearing in a long-awaited trial that accuses ex-President Ion Iliescu, who assumed power in the aftermath of Ceausescu, of crimes against humanity.

Prosecutors hold Ion Iliescu, now 89 and in poor health, and two of his former peers, responsible for "contributing to the institution of a generalised psychosis" during the 1989 revolution, and for the deaths of 862 people. More than 5,000 people are set to testify in the trial.

More than 1,100 people were killed during Romania's 1989 revolution.

Vasile Giurcanu was 50 when he was killed during Romania's 1989 revolution

A visibly emotional Mr Giurcanu, who was just 16 when he took to the streets during the 1989 revolution, recalls his heartbreaking personal story from the night of 23 December 1989.

"My father noticed I hadn't come home so he went out looking for me," he says. "I found my father dead in the street when I was on my way home. He died after taking 13 bullets. It was a machine gun," he says.

"It was terrible, it changed our lives altogether and we never found out who shot my father after 30 years," he adds.

Aurel Dumitrascu, 44, is also seeking justice in the trial. He was a young boy during the revolution.

"I was shot from three metres away, from a car," he says, pulling up his right sleeve to reveal a bullet wound on his forearm.

"They shot everybody on the sidewalk, I was 14 at the time."

The "Revolution trial" has been postponed until February 2020.

Why prosperity has left some Romanians behind

Turbulent years followed the revolution with a government led by Mr Iliescu. In 2007, Romania joined the European Union, which has led to varying degrees of prosperity.

Romania's economy has grown impressively, but even today it is one of Europe's poorest countries. While many cities - including Bucharest - have thrived, the countryside, where around 45% of the population live, can feel as though it has been left behind.

Sitting in their small kitchen in the remote Transylvanian village of Cris, smallholder farmers Marcel and Niculina Taropa, both in their 40s, reflect on 30 years since the fall of communism.

"We were happy because we thought better times would arrive," Mr Taropa reflects. "But not much has changed, we don't have [good] roads, motorways, and the healthcare system is getting worse," he says. "It was better [during communism] because work was stable."

Niculina and Marcel Taropa say the better times they had hoped for have yet to arrive

Mr and Mrs Taropa agree that freedom of speech is a valuable change from communist times, but also agree that the economic benefits since 1989 haven't stretched as far as they'd hoped.

"Sewage, water, and gas — these are all things we should have in our village," says Mrs Taropa. Without gas, most villagers here heat their homes with firewood, as do 3.5 million households in the country.

Around 70% of Romania's rural population are living below the poverty line, according to World Bank statistics.

"People aren't paid enough here [in Romania]," Mrs Taropa says. "The population in the villages have aged and the young people have left to go abroad."

Why Christmas opens old wounds

High levels of migration is one of many issues that blights Romania today.

As many as four million people have left Romania in search of better lives and higher wages since it joined the EU. High levels of official corruption has also driven people to leave the country.

In recent years, anti-government protests have plagued Social Democrat-led governments that set about rolling back anti-corruption measures and undermining the independence of the judiciary.

Mass protests in 2017 against the measures sparked the biggest anti-government protests since the 1989 revolution.

Protesters wave Romanian flags at an anti-communist demonstration in Republic Square, Bucharest, 21 December 1989

Despite myriad issues, Traian Rabagia says: "It's probably the longest and strongest democracy in [Romania's] history."

In downtown Bucharest on a freezing December evening, a bustle of shoppers weave in and out of heavy traffic and under the bright lights of capitalism and Christmas. Thirty years ago, it was an unthinkable scene.

But for some, like Mr Giurcanu who lost his father during the revolution, Christmas merely opens up old, unhealed wounds.

"For everybody else Christmas is Christmas, but for us it's just remembering how our fathers, our sons, our mothers, ended up in coffins," he says.

"The Christmas tree which my father bought for our family ended up in his coffin like flowers."

- Published26 January 2012

- Published8 April 2019

- Published19 May 2014

- Published10 December 2010