Child prodigies: How geniuses navigate the uncertain journey to adulthood

- Published

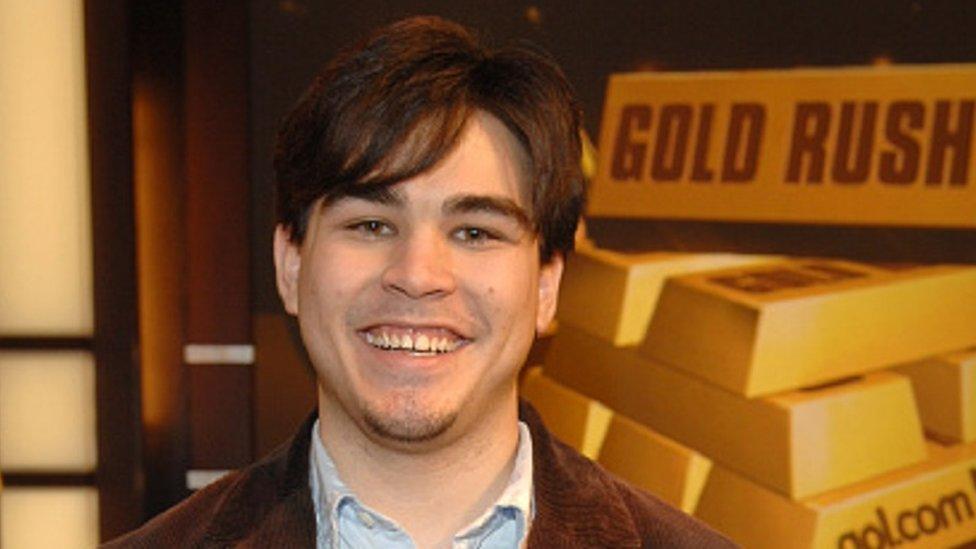

Michael Kearney, pictured here at the age of 22, won the $1m grand prize in game show Gold Rush in 2006

Before Michael Kearney could walk, he had started to master the English language. From as young as four months old - when he spoke his first word - Michael bore the hallmarks of a child prodigy.

Home-schooled by his parents, Michael's intellectual development accelerated at a head-spinning pace. Fast-tracked through high school and college, Michael enrolled at the University of South Alabama in 1992 at the age of eight.

Two years later, aged 10, he walked out with a Bachelor's degree in anthropology, entering the Guinness Book of World Records as the youngest ever university graduate - an extraordinary feat that remains unsurpassed to this day.

More academic success - including two Master's degrees - followed in his teens and 20s, culminating in a PhD and a trivia-and-puzzle game show appearance that saw him win $1m, external (£759,000).

What happened since then is less well-documented. Beyond the late-2000s, Michael's online footprint amounts to a few bread crumbs. Nowadays, the BBC understands the 35-year-old lives a private life, his last known whereabouts in Nashville, Tennessee.

From master musician Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to gifted mathematician Ruth Lawrence, no two child prodigies are the same. Yet Michael's case is a reminder that childhood precocity does not necessarily guarantee enduring success and attention throughout adult life.

Laurent Simons, a nine-year-old Belgian whizz-kid, shows all the same promise that Michael once did. He, too, possesses exceptional talents that he has channelled into academic pursuits. If Michael's university record was to be broken, Laurent seemed like the kid to do it.

He first made headlines in 2018, when, at the age of eight, he graduated from secondary school alongside 18-year-olds. Like Michael before him, Laurent, who is said to have an IQ of 145, became the centre of media attention.

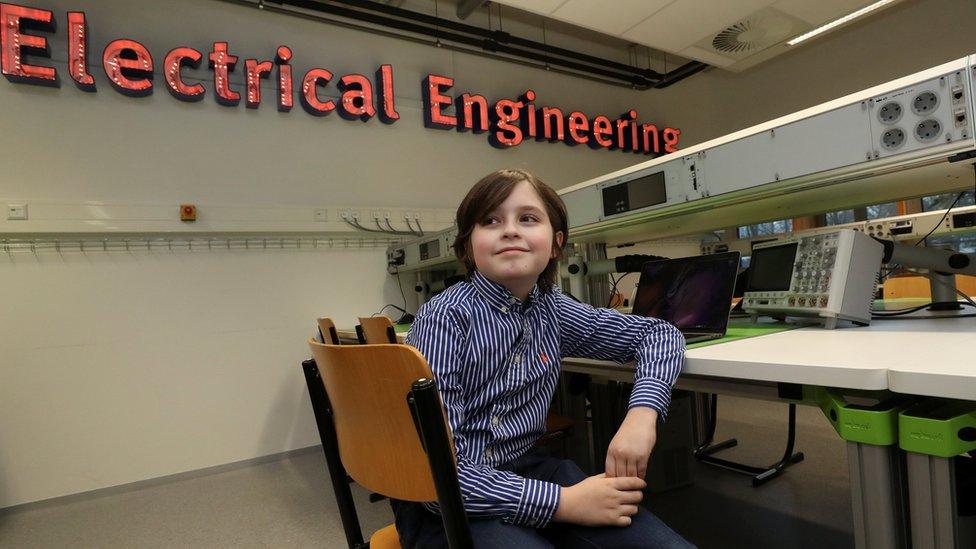

With his child prodigy credentials cemented, the next step was a degree in electrical engineering at the University of Eindhoven in the Netherlands. As of November, Laurent was on track to complete the three-year course before 26 December, his 10th birthday.

Laurent Simons, aged nine, was studying for a degree in electrical engineering at Eindhoven University

Michael's long-standing record, it seemed, was in his sights.

But earlier this month, the university said it would not be feasible for Laurent to complete the course before he turned 10, and offered him a mid-2020 graduation date, instead. His parents, Alexander and Lydia, refused the offer and immediately removed him from the course. He would continue his studies at a university in the US instead, they said.

In its defence, the university said if Laurent were to rush the course, his academic development would suffer. The university also cautioned against placing "excessive pressure on this nine-year-old student" who, it said, had "unprecedented talent".

Laurent, pictured with his parents Lydia and Alexander, was aiming to complete the three-year degree course in just 10 months

Record-breaker or not, Laurent's academic progress so far has still been exceptional by historical standards. He is still expected to graduate from university, whenever and wherever it happens.

If the pressure to do so has become more intense, Laurent is not showing it. In interviews, Laurent seems self-assured and optimistic for a future flush with endless possibilities. Studying medicine and making artificial organs are among his to-dos.

Laurent has what Ellen Winner, a professor of psychology at Boston College, calls a "rage to master", an unstoppable motivation to excel in his domain of ability. When Laurent is an adult, he may reach the limit of that ability, allowing other bright individuals of a similar age to catch up. As a result, Prof Winner said, Laurent's talents as a child might seem less special as an adult.

"When prodigies do not make the transition to adult creator, they may feel like failures," Prof Winner, author of Gifted Children: Myths and Realities, told the BBC. "No-one cares anymore that a 21-year-old can play the violin with great expertise or ace calculus or understand Latin and Greek."

Psychology professor Ellen Winner said Laurent had a "rage to master"

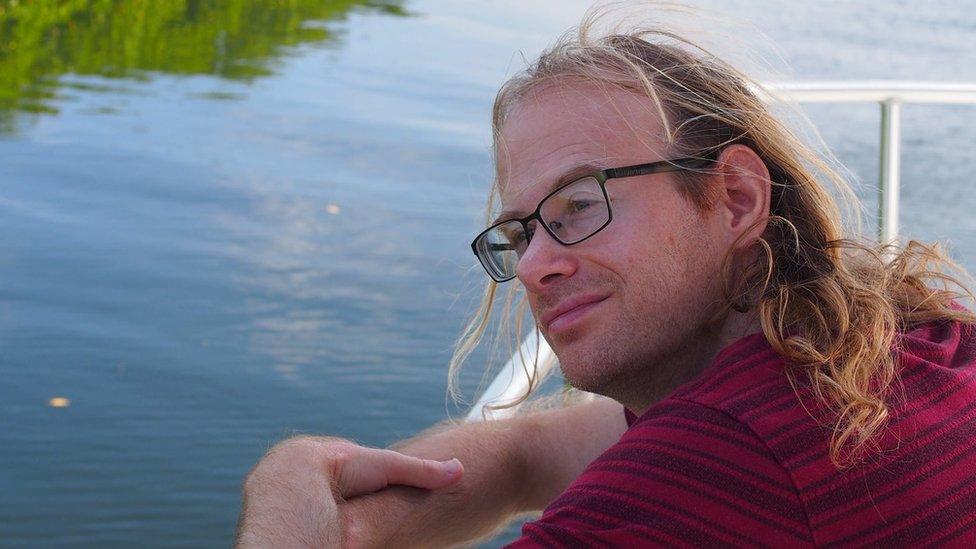

As a former child prodigy, Gabriel Carroll, now in his 30s, said he felt awkward when others talked about his illustrious past.

"I think gee, have I not done anything since then," he told the BBC.

But Gabriel's adult life has been far from a failure. An assistant professor of economics at Stanford University, Gabriel pursued a career in a field related to his gift: solving mathematics puzzles.

In his seventh grade SAT [Scholastic Assessment Tests] exams, Gabriel achieved the highest score in California, including a perfect 800 in mathematics. In high school, his mathematical prowess was put to the test against the world's best young minds at the International Mathematical Olympiad, where he won two gold medals in 1998 and 2001.

When speaking about his achievements, Gabriel struck a humble tone, more comfortable at pointing out his weaknesses than his strengths.

In seventh grade, Gabriel Carroll achieved the highest SAT score in the state of California

"I feel less developed in the areas of social and emotional skills than perhaps I would have been had I not been so technically focused," Gabriel said.

He credited his parents, both tech industry workers in California, with instilling him with that focus. They were "extremely important" in his development, teaching him mathematics and giving him puzzle books to solve from age six. Reflecting on his upbringing, Gabriel said he felt "very lucky on the whole" but did have "a couple of regrets when one thinks about how much agency one has as a child".

You may also be interested in:

Meet the schoolboy with a higher IQ than Bill Gates and Albert Einstein

By agency Gabriel meant the capacity to act independently, free from the overt influence of parents. This has particular relevance in the context of child prodigies, whose parents are commonly depicted as pushy, domineering and overbearing.

Jennifer Pike, a British violinist who burst on to the classical music scene as a youngster, said the parents of child prodigies were often stereotyped in this way.

"I'm aware of the myth, or popular belief, that parents must somehow be pushing their young child into living their dream," Jennifer told the BBC. "I think that's a trope that's definitely true in some cases, but not the case for most."

Jennifer Pike, a violinist, won the BBC Young Musician of the Year competition at 12

For Jennifer, it was she who took the lead, not her parents. That self-determination was evident in 2002, when Jennifer won the BBC Young Musician of the Year competition aged 12. At the time, she was the youngest winner of the award, a record she held for six years.

From that moment, her biggest challenge has been "overcoming that perception of you in one moment in your life".

"People want to keep you in this box," Jennifer, now aged 30, said.

Jennifer said the parents of child prodigies were often stereotyped

Anne-Marie Imafidon, a tech entrepreneur with a master's degree at the University of Oxford, said she couldn't imagine a life outside that box.

"I've only ever had the label," she told the BBC.

The label has stuck since Anne-Marie and her four siblings were dubbed "Britain's brainiest family" by the UK media. At school, computing, mathematics and languages were her forte. She passed two GCSEs while still at primary school and, at the age of 11, became the youngest person to receive an A-level in computing.

Anne-Marie Imafidon has a master's degree from the University of Oxford

Almost 20 years on, Anne-Marie said she had nothing left to prove, mostly because she never saw herself as a genius "you see in the movies", a Rain Man-type. Excelling in her domain of ability - mathematics and computer science - is enough for Anne-Marie.

The difference between an adult genius and a child prodigy is an important distinction, Prof Winner said. A prodigy is a child who is very precocious in a certain field, mastering a domain that has already been invented, she says. A genius, she believes, is someone who revolutionises a field of knowledge.

"Most prodigies do not make the leap in early adulthood from mastery to major creative discoveries," Prof Winner said. "Some do, most do not. Instead most become experts in their areas of giftedness - professors of math; performers in an orchestra, and so on."

Like Anne-Marie and Gabriel, Jennifer said she "never defined success in terms of achievements in that way". Her life goals are far more modest.

"I'm just happy to have a career and to have survived the journey," Jennifer said.

Laurent said he had #giganticplans for the future in a post on his Instagram account

Surviving the journey from childhood to adulthood with their aura of success intact is exactly what Jennifer, Gabriel and Anne-Marie have done. Their gifts have transcended childhood, delivering them to the promised land of recognition - their Wikipedia pages and websites brimming with accolades.

As for those child prodigies who did not, they are a cautionary tale for the next generation.

For now, Laurent is embracing the limelight, posting about his #giganticplans to his 64,000 Instagram followers, external. But Prof Winner said child prodigies like Laurent should be wary of the public stage. Given the trials and tribulations of adult life, it does not take a genius to figure out why.

- Published10 December 2019

- Published11 December 2019

- Published16 August 2018