Strongman Putin stokes patriotism in small-town Russia

- Published

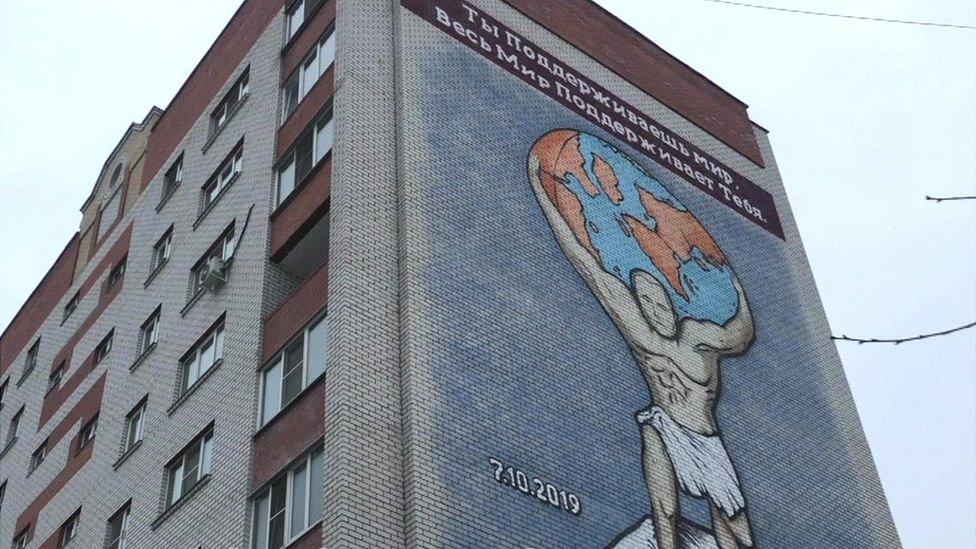

A mural in Kolomna shows Vladimir Putin as an Atlas figure carrying the globe

Kolomna has many stunning sights.

This ancient Russian town has its own Kremlin and a myriad of onion domes from monasteries and churches.

But what catches my eye is an ordinary nine-storey apartment block by the railway station.

I say ordinary. But that was before someone painted a giant mural of Vladimir Putin on the side of the building.

On Apartment Block 25 on Polyanskaya Street, President Putin is half naked, wearing only a towel, and sporting bulging muscles. He is depicted holding up the world, rather like Atlas the Titan from Greek mythology who held the celestial heavens.

Atlas was famed for his endurance. So is Mr Putin: he's been in power in Russia for 20 years. The residents of Apartment Block 25 appear in no hurry to see him go.

President Putin visited a perinatal centre in Kolomna two years ago

"Putin has made Russia's position in the world stronger," Vladimir tells me. "Let him have another 10 years in office."

"I was 10 when Putin came to power," says Ilya. "Now I'm 30. I can't really imagine any another leader."

"We live badly," admits Tatyana, "but at least the world takes notice of Putin."

'There will be war anyway'

At the Patriotic Youth Centre across town, high school students are being shown a film about a local hero. Vasily Zaitsev was an ace fighter pilot in World War Two, twice awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union.

A statue of World War Two Russian fighter pilot Vasily Zaitsev sits in the middle of the town

President Putin has made the Soviet victory in World War Two a key element of Russia's national idea.

But as I'm about to discover, there is a fine line between patriotism and nationalism.

Vyacheslav Burilov, the former head of the Kolomna Flying Club (Helicopter Section) gets up to make a speech.

"Unfortunately, our country, the USSR, was destroyed," he tells the young audience.

"And much of Russia's land went to other countries, which is not right. Like Ukraine, Belarus, parts of the Baltic states and part of Kazakhstan. You must make sure this land is returned to Greater Russia. And don't be scared if you hear people say, 'There mustn't be war.' There will be war anyway."

The students respond with applause.

I follow the group as they walk through the slushy streets of Kolomna to Vasily Zaitsev's monument and lay red carnations. Mr Burilov from the Flying Club is there. Astonished by his call to arms, I approach him.

"What you're calling for," I tell him, "means a major war."

Vyacheslav Burilov, the former head of the Kolomna Flying Club

"It won't be a big war," he assures me. "We have nuclear weapons. If our authorities are decisive and strong, our opponents won't want to fight."

A man called Alexander joins our conversation and starts to criticise the authorities.

"The only time they think of us is when they need our taxes, our votes, or cannon fodder for their wars. There are so many negative things."

Hearing my accented Russian, he suddenly goes quiet.

"Just a minute, are you a citizen of Russia?" he asks.

"No, I'm British."

"In that case, there's no point in me spouting on," concludes Alexander. "Just so you know, we love Russia, we love our country. We are patriots!"

For some in Kolomna the more important battles are closer to home.

A landfill in Kolomna was recently shut after protests

Local activist Vyacheslav Yegorov takes me to a landfill on the edge of Kolomna. Concerned by its overuse and the noxious smell, campaigners fought hard to get the dump shut.

Its closure is a victory for people power. But only partially. In connection with the protests Vyacheslav is facing criminal charges. Russia's leading human rights group, Memorial, has concluded that the case against him is politically motivated.

Vyacheslav claims that Russia's FSB intelligence service had tried to weaken the protests by attempting to discredit him.

"They claimed I was working for the US State Department and that I had billions stashed away in Swiss bank accounts," he tells me.

Some Pensioners, many of which are struggling, have to queue up for soup

Back in town I head to the Church of St John the Apostle, where a priest is reciting prayers in the soup kitchen.

For the two dozen pensioners queuing up here, the only battle they are waging - in difficult economic circumstances - is for their own survival.

"My gas and electricity have been cut off," Olga tells me. "I have no money to pay the bills. My pension doesn't cover it. And as for prices in the shops, everything is so expensive."

Olga tells me it's not just the free meals that bring her to church. She comes here to pray.

A church in Kolomna

For in Kolomna the power of prayer is legendary. According to one story, when the town was attacked by foreign invaders, hundreds of years ago, the townsfolk took refuge in a church. When they prayed for help, the ground opened and the church and parishioners were hidden underground, while the church bells inspired the local soldiers to keep fighting.

In today's Russia, part of the population are counting on their president to make life better. Others have decided they can only rely on themselves.

And some Russians are still hoping for a miracle.

- Published14 December 2019

- Published14 January 2020