Serbia migrants: The man offering heat to people rejected by Europe

- Published

Pastor Tibor Varga with one of his basic barrel stoves for migrants

Some 100 people daily are trying to cross into Hungary from Serbia and Romania, in what Hungarian border police see as a new migrant surge.

The Hungarian government has sent military and police reinforcements, including a naval gunship on the Tisza river, to keep them out. Some have been trying to reach Hungary by rubber dinghy.

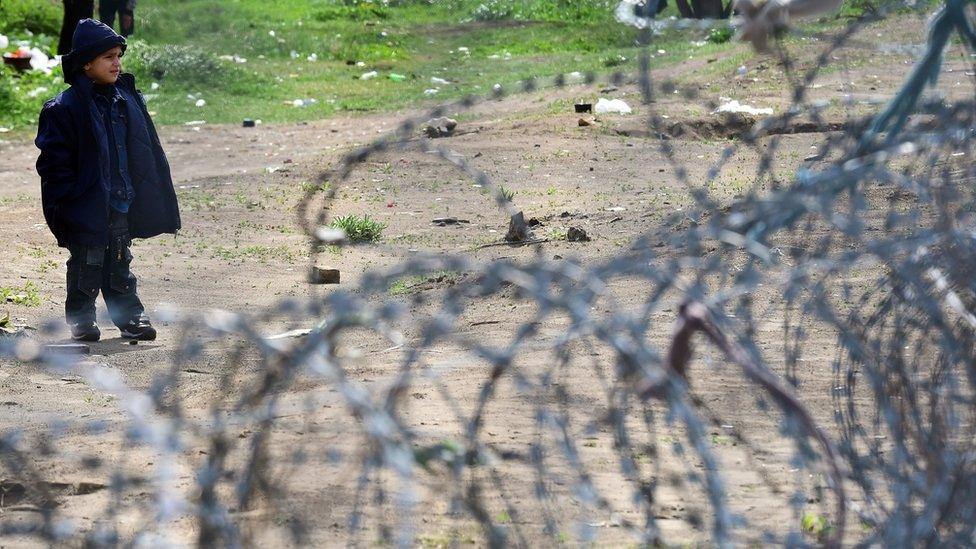

Hungary has a razor-wire fence along its border with Serbia. It was erected after the 2015 crisis, when more than a million migrants - many of them refugees from Middle East conflict zones - reached Central Europe.

Many of the migrants gather inside the border in the Serbian town of Subotica, where a Protestant pastor from Serbia's Hungarian minority helps them keep warm.

Tibor Varga crafts stoves for the migrants out of old barrels in his garden. This is his third in a day.

Pastor Varga believes it is wrong to dump people out in the cold

He reinforces the base and thin metal walls of the barrel with old roof tiles, held in place with a mixture of clay and sand.

He scrapes off the red paint, to stop it poisoning the people he wants to keep warm. Then he loads the 30kg (66-pound) stove into his van, and drives it to the old railway sidings nearby.

Derelict buildings where migrants now shelter: Smoke from a stove billows out of a roof

Serbian charities estimate around 500 men are living in derelict buildings in and around Subotica.

Many have come from refugee camps in Bosnia-Herzegovina, after failing to cross from there into Croatia. Others are new arrivals from Greece.

Those who try to cross into Hungary frequently allege police brutality as they are caught and pushed back into Serbia.

Read more on related topics:

Between 30 and 60 migrants - mostly from Afghanistan, they say - huddle in and around three derelict brick buildings dating back to the Austro-Hungarian empire.

Inside the squalid ruins where migrants remain exposed to the cold

They emerge cautiously from the freezing fog to greet the Hungarian priest, who sees it as his Christian mission to help all those in need.

Around a fire fuelled by old railway timber, five men cook eggs in an iron pan.

Migrants burn old railway timber as they struggle against cold and hunger

In one ground-floor room, with a blanket over the doorway and plastic sheets in the window, about 10 men sleep on insulation sheets. They have sleeping bags and blankets, but not much else, only flimsy shoes and clothes.

Another of Tibor's stoves in the corner pumps out a pleasant heat.

But it's a long way to the nearest tap, and the men depend on occasional deliveries of rice, sugar, bread and oil to keep them alive.

The arrival of a barrel stove brings some comfort

Upstairs, a smaller group of men say they're Syrian Kurds from the city of Afrin, now held by Turkish-backed rebels.

In the crowd outside one young man, Ali, recognises me - we last met in Sofia, Bulgaria, in 2016.

"I made it straight from there to France. I stayed there two years, then was deported back to Bulgaria. I had several months in the asylum detention camp at Busmantsi - now I'm trying again."

Every day we need to intercept more than 100 people crossing the border illegally; we need to intercept them, detain them and transport them back

A 14-year-old boy describes how, when he crossed the Hungarian border fence a few nights earlier, police kicked him, forced him to walk barefoot, and poured cold water down his neck. Many of the men here have similar stories.

"Hungarian police and soldiers are defending the Schengen border of the EU for the sixth consecutive year, legally and without violence, against illegal migrants arriving on the Balkan route," the authorities told the BBC in a written reply to these allegations.

A patrol boat joins Hungarian border forces intercepting migrants

Hungary has kept a constant "state of migrant emergency" along this border since 2015, when nearly 400,000 migrants and refugees crossed, before the fences were finished. Since then, the flow has slowed to a trickle.

But now hardline anti-migrant Prime Minister Viktor Orban feels his measures were justified - he has always warned that the "invasion" could restart anytime.

"Unfortunately people often care more for animals than for human beings," Tibor Varga said. "That hurts me. These people are desperately in need of help. I hope we can just alleviate this situation with love and care."

- Published21 May 2019

- Published7 December 2019