'I was 90% dead': Henri's story of surviving Auschwitz

- Published

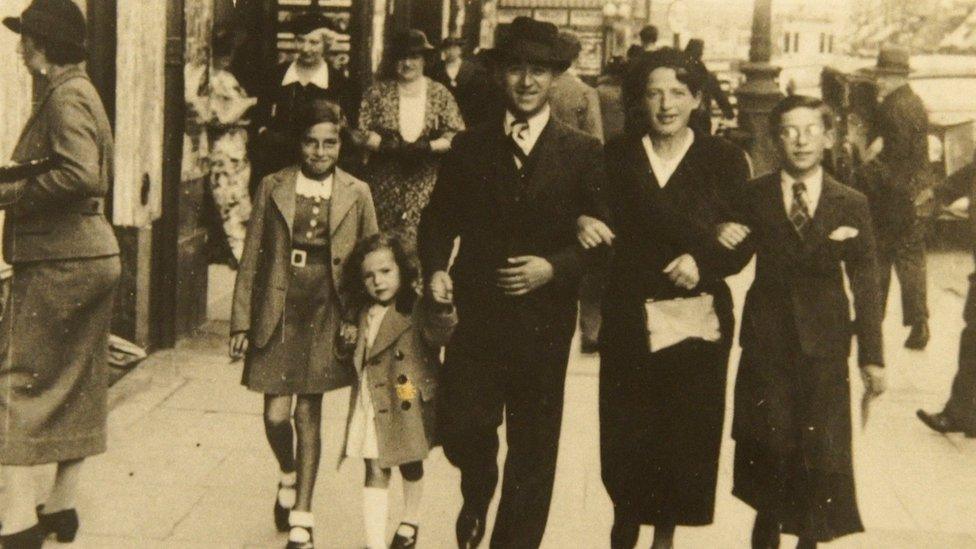

"I was a skeleton" - Henri Kichka lost his whole family in Auschwitz

Henri Kichka knows there will be a price to pay for telling his story: sleepless nights where the horrors of the past seep back into the present.

But he knows the story must be told. Henri is one of the dwindling handful of men and women who survived Auschwitz.

The death camp the Nazis built in occupied southern Poland during World War Two was, another survivor once told me, like a crack in the surface of the Earth through which hell could be seen. And a crack in the surface of our common humanity through which could be seen our capacity for enduring suffering - and inflicting it.

Ask Henri how he lived through it and his answer is simple: "You did not live through Auschwitz. The place itself is death," he tells the BBC, 75 years after it was liberated.

You had no name in the camp - just a number tattooed on to your forearm.

There is a chilling moment when Henri suddenly barks out his own number - 177789 - in German as he was required to when challenged by the guards.

"Hundertsiebenundsiebzigtausendsiebenhundertneunundachtzig, Heil Hitler!"

Henri was born in Brussels to parents who had fled anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe to build new lives in the West.

When Nazi Germany invaded and occupied Belgium, they were left with nowhere to hide.

Henri Kichka's parents had moved to Belgium to escape anti-Semitism

In the first week of September 1942, they were taken from their home in the Rue Coenraets. The German soldiers who sealed off the street in the middle of the night went from building to building shouting: "Alle Juden raus!" (All Jews out!)

It is hard to establish now to what extent the Jews of countries like Belgium, the Netherlands and France knew the fate that awaited them in the East, but Henri can remember some of the Jewish women in his street throwing themselves from upstairs windows with their babies, killing themselves as the last desperate way to avoid the round-up.

Within a week, the family was in a convoy of cattle wagons on a railway transport heading back east - first to Germany and then, ominously, onwards to occupied Poland.

Henri and his father, Josek, were taken off the train with the other men in the small town of Kosel. They were to work as slave labourers, destined to be murdered in the gas chambers only when they were no longer of economic use to the Third Reich.

The women of the family - Henri's mother, Chana, his sisters Bertha and Nicha and his Aunt Esther - were taken to Auschwitz where they were gassed and cremated as soon as they arrived.

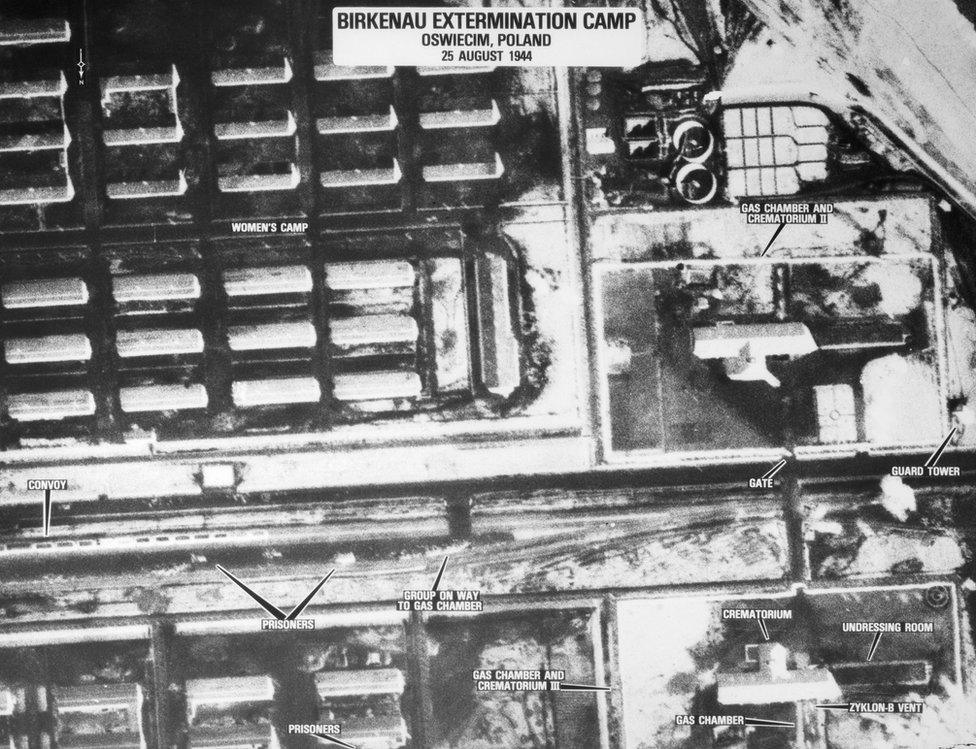

This August 1944 aerial picture shows the Auschwitz II (Birkenau) camp while mass murder there was still taking place

The fate of the Kichkas captured perfectly the dual purpose of the Nazis' vast network of camps which spread over much of occupied Europe.

There was the task of exterminating the Jews of Europe - Hitler's "Final Solution" to the "Jewish Question". But there was also the need to provide slaves for the factories, mines and railways on which the German war economy relied.

It is difficult to ask Henri to talk about the camps - the sheer scale of the suffering feels overwhelming.

"It is the only concentration in the history of the world where a million people died," he says simply. "The only one, Auschwitz. It was horrible and now I am one of the last survivors."

There was cynicism as well as unfathomable wickedness in the way the Nazis ran the camps.

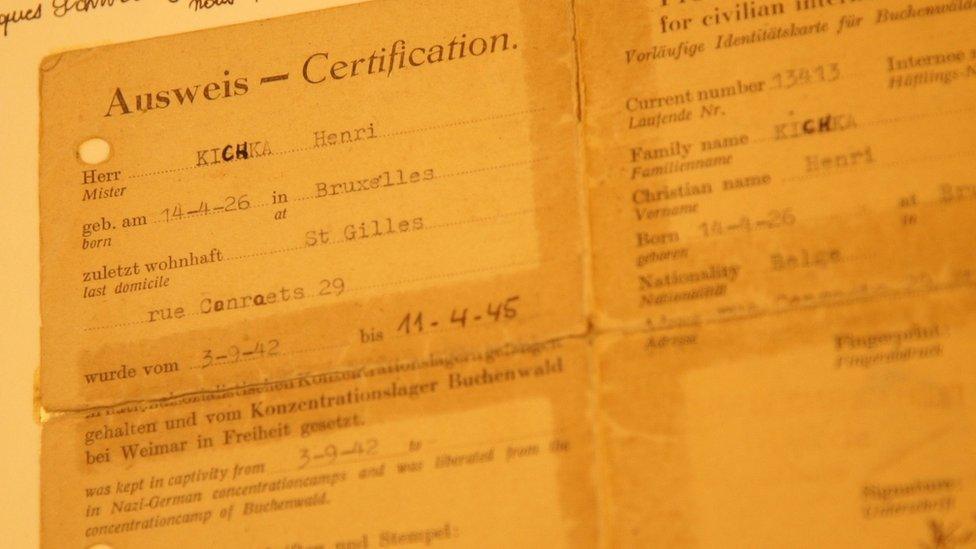

Henri Kichka's old ID card spells out the time he spent in Nazi concentration camps from September 1942 to April 1945

To make the incoming transports easier to handle, the fiction was maintained until the last moment that the trainloads of Jews were being taken to huge communal showers on arrival to delouse them after long journeys in cattle wagons without water or toilet facilities.

There was no water in the showers. The camp authorities fed in a gas called Zyklon B which had originally been developed as a pesticide.

In the earlier part of the war, the Germans had experimented with a kind of "Holocaust of Bullets" using special squads of soldiers called Einsatzgruppen to wipe out the Jewish population of Eastern Europe by shooting them.

There was no shortage of volunteers for the work, but the sheer scale of the task made it impractical.

Auschwitz - a huge complex of low, shed-like structures grouped around an old Austro-Hungarian cavalry barracks - was the answer to that problem of scale. It married the technology of the railway and the factory with the murderous intent of the Holocaust.

On its busiest day in 1944, 24,000 Hungarian Jews were murdered and their bodies consumed in the fires of specially built ovens.

More than 430,000 Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz

When the first reconnaissance units of the Soviet Red Army arrived as they drove the Nazis back west towards Germany, they found Auschwitz more or less deserted.

The Nazi guards had forced the starving, emaciated prisoners on "death marches" westwards, towards camps in Germany.

At this point, Henri Kichka, a tall young man of 19, weighed 39kg (85lb) and to this day he suffers from the injuries he sustained from the long march on broken and bleeding feet through the snows of January in Eastern Europe.

"I was 90% dead. I was a skeleton. I was in a sanatorium for months and in hospital."

For years after the war, Henri never spoke of that suffering as though his memory was overwhelmed by darkness.

He married, opened a shop with his wife, and built a family: four children, nine grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren. The man who had cheated death drew strength from creating new life.

He started to give lectures in schools too, feeling it was worth suffering the pain of remembering himself to make sure that others did not forget.

Henri Kichka sits surrounded by his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren

Sixty years after the war ended, Henri published a memoir of his life in the camps, which means his voice will still be heard when he is gone.

His daughter, Irene, who helped him with the book, stresses the importance of listening to survivors like Henri who lived through history's darkest chapter as they tell their own stories.

"It's necessary to have books, films and documentaries. of course," she says. "But when you hear it from someone's own lips in their own voice, it stays in your head. You never forget."

Henri Kichka despairs of the way anti-Semitism survived into the modern world in spite of the Holocaust. "Why make enemies of the Jews?" he says. "We have no guns, we are innocent. I don't understand why people hate us so much."

As I leave, I apologise for taking him back one more time through his suffering, and for a moment, there is a distant look in his eyes as though he is seeing the past.

But he is happy, he says, to talk about the things he would prefer to forget if it means that the rest of us remember.

Find out more about Auschwitz and the Holocaust:

Explaining the Holocaust to young people

Henri Kichka died in April 2020, a few months after he spoke to the BBC's Kevin Connolly.