Blood on the tracks: Russian mystery of drummer's death in Siberia

- Published

Dmitry Fyodorov was found dead 10 days after police accused him of selling drugs

He was 25 and an aspiring drummer with an eye on a career with the band he formed with his college friends. Dmitry Fyodorov was also planning to marry his girlfriend in the Siberian city of Omsk.

But last month, police broke the news to his family that he had been decapitated by an oncoming train because he had ignored a driver's warning signal to get off the tracks.

His friends do not believe a word of it and say he would never have taken his own life.

Before he died, Fyodorov posted a video saying he had been framed by police and his fiancée says while there was some blood on the tracks, it was not enough to suggest such an appalling accident.

Fyodorov's body was found on railway tracks a short distance from his home

His case is being linked to that of a high-profile journalist who was detained and beaten by police officers who planted drugs in his rucksack.

Framed by the law

Ivan Golunov was freed after a public outcry and street protests, and five former policemen were charged last week with falsifying evidence against him.

Ivan Golunov appeared in court in Moscow in June 2019 accused of drug-dealing

Fyodorov's story resonates across Russia because one in four prisoners in Russian jails are convicted of drugs offences and it is all down to an infamous drugs law. Article 228, known as the people's article, covers all aspects of obtaining, keeping and transporting drugs.

In 2018 alone more than 70,000 people were convicted of drug-related offences.

Ten days before his death Dmitry Fyodorov described being collared by two National Guard officers (military police) who claimed they suspected him of selling drugs.

He posted a video on social media describing how he had disappeared for almost 24 hours in a rough part of Omsk. Looking very anxious he implores his followers to repost the video as widely as possible and tells his story.

"It could happen to anyone," he warns.

Fyodorov's girlfriend says that officers encouraged him to admit to selling drugs to avoid a jail term

"One of the officers put his hand into my left pocket and then a little bundle fell on to my feet which wasn't mine and couldn't possibly be mine," he told his lawyer. "Then he shoved his hand again into my empty left pocket and pulled out four more little bundles just like the first one."

He then said police were called and he was held all night at a police station without the right to make a phone call or see a lawyer. Police alleged that five one-gram packages of methylephedrine were found on him.

A fiancée's story

Lyudmila told BBC Russian that things went from bad to worse for her boyfriend that night.

She says the officers made him admit on camera to being a dealer; they took away his phone and wanted him to sign statements that he was in that part of town to deliver drugs. This way, they told him, he'd get a suspended sentence but otherwise he'd go to jail.

He signed everything but they did not release him until 04:00. Lyudmila says they took him back to the street where they had arrested him and showed him hiding places "where he was going to leave the drugs for collection" and told him to remember for his trial.

Fyodorov was eventually released from the police department in Omsk but legal proceedings soon began

Dmitry met his fiancée Lyudmila at Omsk University where they both studied advertising. By the time of his death, everything was coming together for him. He was about to graduate and his band was securing gigs at festivals. They were about to record a mini-album.

But on 16 December 2019, the day after his arrest, criminal proceedings began. A lawyer assigned to his case urged him to co-operate fully and sign a statement that a search had been carried out in his flat. That had not happened, but he signed nevertheless and found another lawyer, Igor Suslin.

His new lawyer filed complaints alleging Fyodorov had been stitched up. They took the case to the local headquarters of the federal security service (FSB) to complain that drugs had been planted on the young musician and went to the local court too.

Then Fyodorov posted a video on social media platform VKontakte.

Dmitry's last days

He celebrated his birthday on 21 December but told his lawyer he was in despair. He had no hope of a fair trial in Russia and believed his complaints would fail.

Conviction rates in Russian courts are very high and rights activists say the police practice of forcing suspects to sign false confessions is endemic.

On 26 December Fyodorov was supposed to discuss his case with a National Guard security officer and a local MP.

But Fyodorov did not show up. Igor Suslin feared he had been abducted and went to the police. Then Fyodorov's father received a phone call and was told he had been hit by a train.

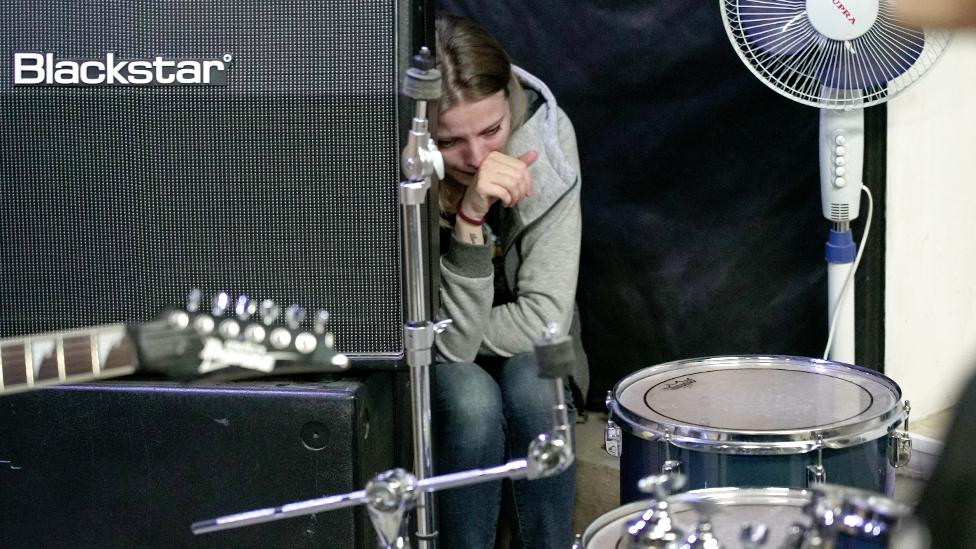

Lyudmila attended her late fiancé's first band rehearsal after his death

Police held a briefing the next day and told journalists there was evidence of drug dealing on Fyodorov's phone. Lawyers have not been allowed to see it.

Fyodorov's girlfriend says there was little blood on the tracks where he was said to have died. She also believes the way his head was severed is inconsistent with a rail accident.

The prosecutor has said information cannot be disclosed about the case, which is continuing.

However, a source in Russia's investigative committee has told the BBC that the train drivers saw a man standing beside the tracks on the day. And when they sounded and hit the brakes the man did not react.

Another case centred on Fyodorov's allegations of falsified documents has been opened by the investigative committee. A disciplinary investigation has begun against his first lawyer.

His tragic death is in stark contrast to the crowds that welcomed the release last June of journalist Ivan Golunov. But both cases shed light on Russia's notorious drug law, article 228.

- Published12 June 2019