Coronavirus: Quarantine raises virus fears in northern Italy

- Published

Mark Lowen was on the ground at the edge of Italy's coronavirus lockdown area

In an era of online ordering and borderless travel, Tino has had to revert to hand-delivering items across a checkpoint - within his own country.

He parks beside the police cars blocking a road to Codogno, the epicentre of Italy's coronavirus outbreak. And across the ad hoc barrier, fencing off an invisible threat, he passes a simple object to his sister stuck on the other side: a facemask.

Pharmacies in the town of 16,000 people are running low. Queues of anxious customers are forming, as Codogno hits headlines around the world.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The mayor, Francesco Passerini, tells me by phone that the situation is completely calm and supplies of food and medicine are stable. "Our town has overcome everything, including the Second World War," he says - an attempt at reassurance.

But in the 11 closed-off towns, in which more than 50,000 people are quarantined, fear is setting in.

Andrea Alloni, a resident in Codogno, says while some are convincing themselves that the outbreak will blow over, others are so worried that they're using sleeping pills.

Police have been stopping cars trying to get into Codogno

Emergency medical phone-lines are saturated. The elderly are feeling particularly vulnerable.

And while a handful of shops are open inside the town, the streets are quiet. Most are staying at home - or if they venture outside, they do so in face masks.

Italy is struggling to understand how it went from six coronavirus cases to more than 200 since last Friday, becoming Europe's worst-affected country and the third worst hit in the world after China and South Korea.

So far, seven people have died.

"Patient zero" - the individual first infected - has still not been identified. It was initially believed to be a 38-year-old man who visited a hospital in Codogno where a woman later died from the virus and whose colleague had been in China in January.

But when his colleague tested negative, the search for the original infector continued. Finding the source of the outbreak would help authorities understand the spread and potentially stem it.

Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte has defended his government's response, insisting that the high number here is because Italy is testing more people than other European countries. There is a hope that the outbreak has stabilised, with new cases slowing.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

But the authorities here are worried.

With the unprecedented containment measures widening, the economic impact could be severe.

Public spaces have been cordoned off, schools, universities and museums are closed, key events like the Venice Carnival and Milan fashion week have been curbed, even filming of the new Mission Impossible in Venice has been suspended.

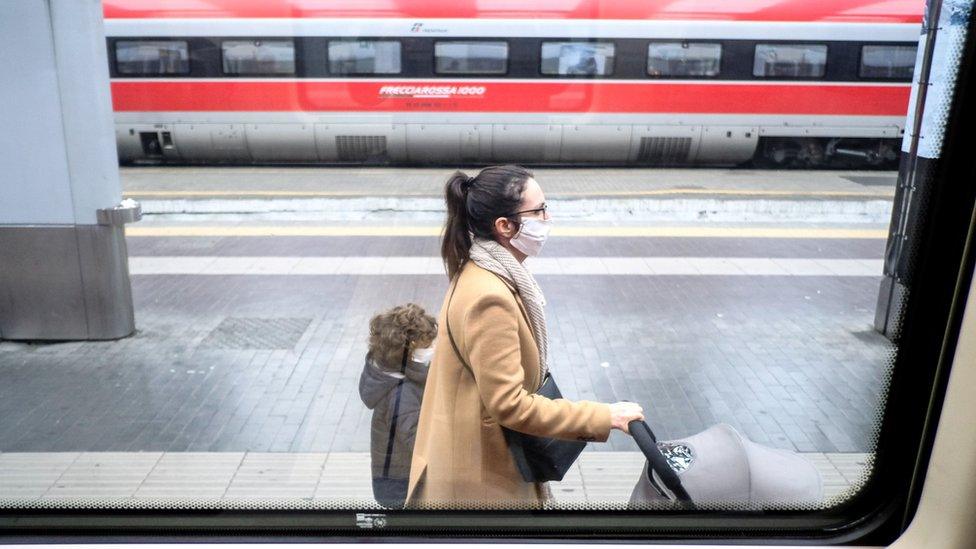

Passengers at the main station in Lombardy's capital, Milan, are now wearing face masks because of the rapid spread of the virus

Lombardy and Veneto - the two most affected regions - make up 30% of the Italian economy. Italy's growth is already estimated at just 0.1% for 2019 - the lowest in the eurozone. The talk now is that the impact of the virus could tip it into recession.

Neighbouring Croatia and Greece have cancelled all school visits to Italy. Kuwait has stopped flights here. Italy itself was the first European country to halt flights to and from China when the outbreak began: a risk for an economy that depends on some five million Chinese tourists a year.

In an era of social media, rumours and scaremongering fly fast.

It's too early to talk of panic here. But some supermarkets are seeing empty shelves, as families stock up.

Bars and restaurants are closing this week - the old town of Piacenza was eerily quiet for a weekday evening. The far-right opposition is harnessing the situation to push its call for closed borders.

"We're confident our public health system can face this if it's a few hundred cases," says Andrea Alloni by phone from Codogno. "But if the number spikes, it won't be able to cope. I pray to God this doesn't happen."

- Published24 February 2020