Spain still haunted by spectre of poverty trap

- Published

Polígono Sur is a short drive from Seville but blighted by poverty

Pedro Araujo Pozuelo stands at the door of his small bar and looks out across the surrounding tenement blocks of the Polígono Sur housing project.

"When you say that you're from this part of town, potential employers look at you in a different light," he says with a sigh. "They always think that you must be bad, that you steal, that you're a drug addict or you've been in prison."

Polígono Sur is just a short drive from the centre of the thriving tourist hub of Seville, in southern Spain.

But local authorities describe it as the poorest district in the country, where unemployment and school drop-out rates are alarmingly high and where drug trafficking is a tempting career choice.

As many as 35,000 people may be homeless in Spain, recent research by charities suggests

"The only ones who receive a fixed monthly payment here are the pensioners," Pedro says. "Hardly anyone has a fixed monthly wage."

Polígono Sur was one of the places that the UN's special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Philip Alston, visited during a recent trip to Spain.

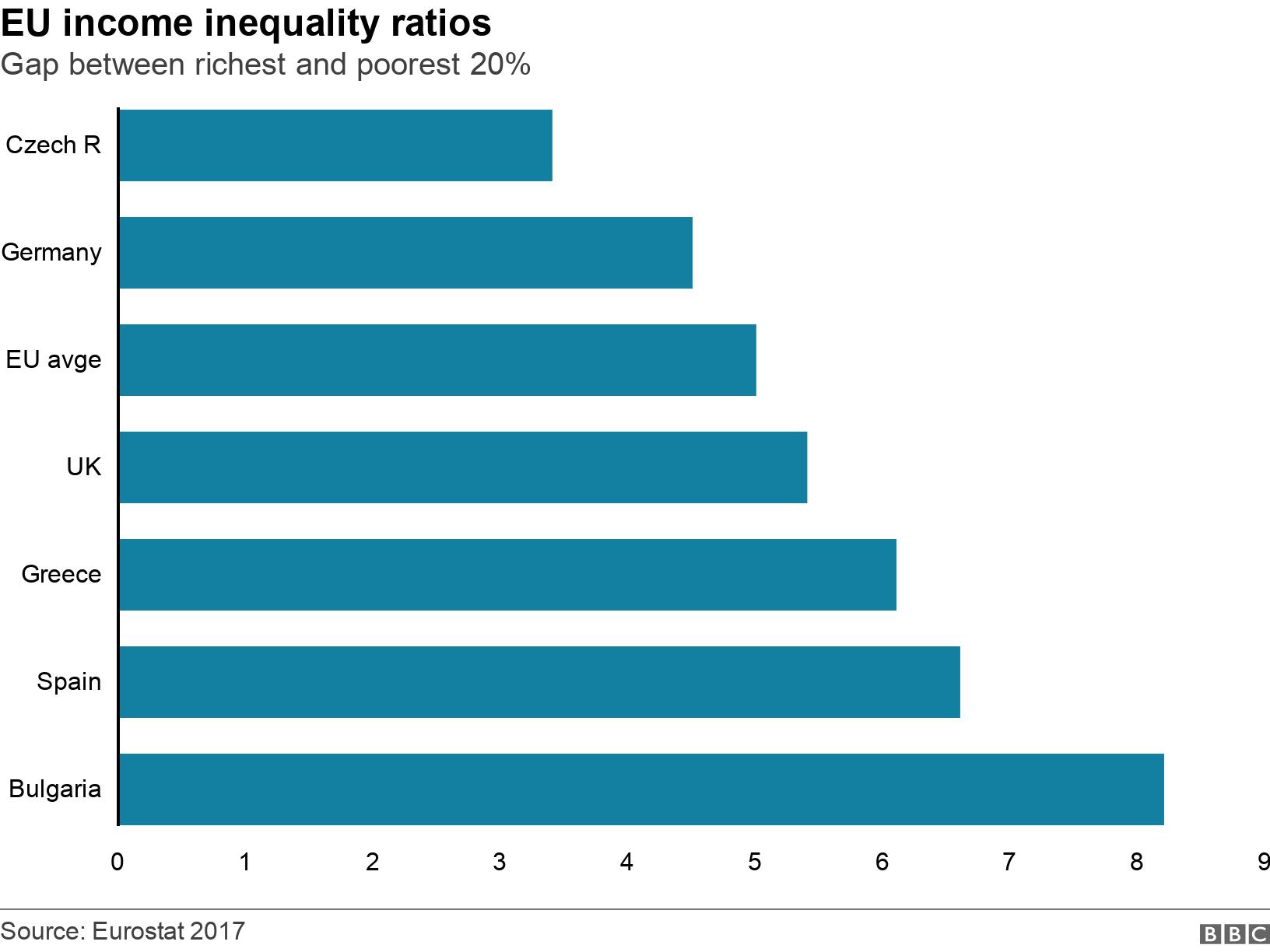

It may be an extreme case, but Mr Alston found that it was symptomatic of the country's social inequality.

The only ones who receive a fixed monthly payment here are the pensioners

"Spain needs to take a close look in the mirror," he said at the end of his visit. "What it will see is not what most Spaniards would wish for nor what many policymakers would intend."

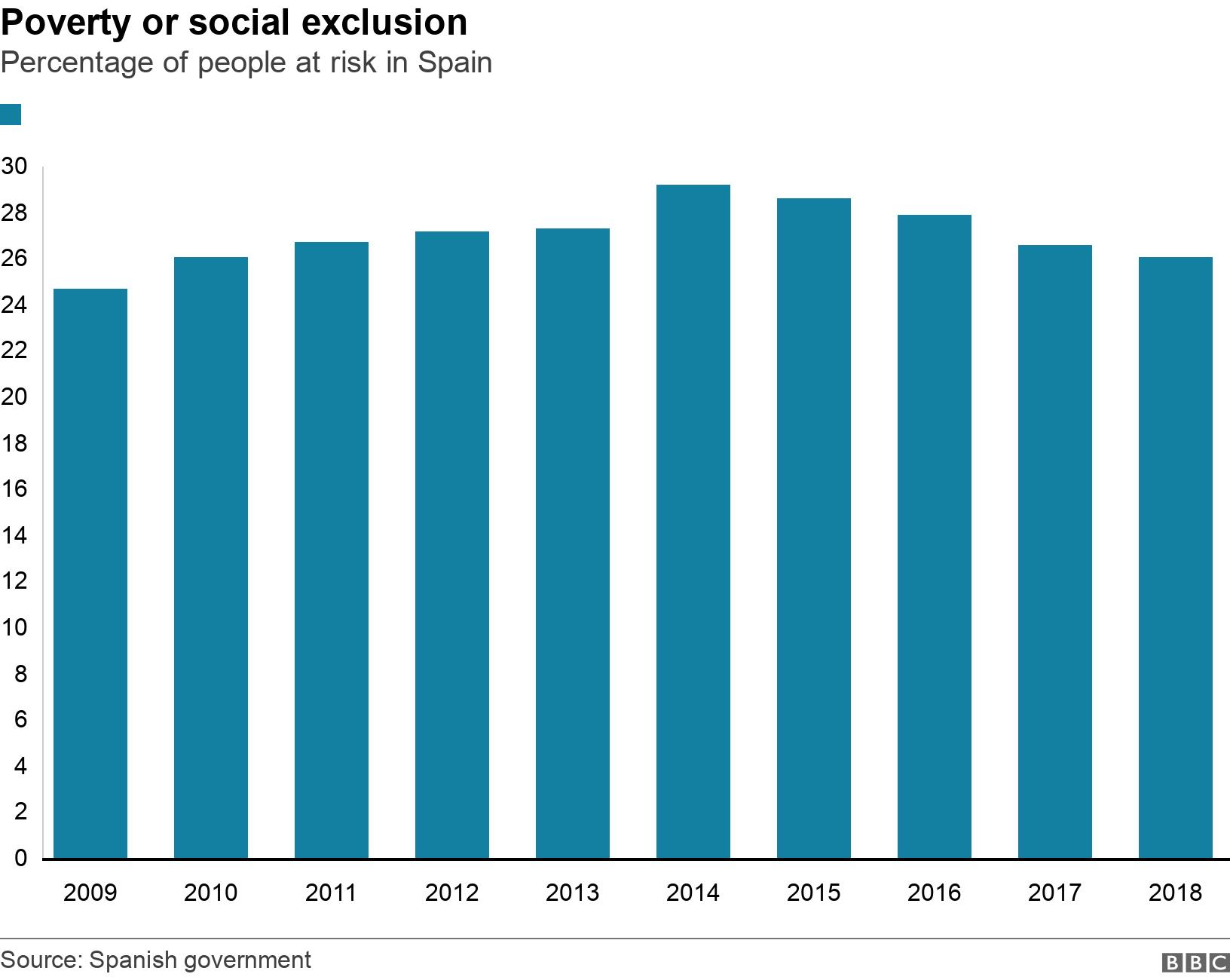

He pointed out that 26% of Spaniards, and 30% of Spanish children, were at risk of poverty or social exclusion, while 30% of young people were out of work.

He also warned of a lack of social housing, a "segregated and increasingly anachronistic" education system and a skewed tax regime, all of which helped accentuate the gap between rich and poor.

Marginalised communities

Such a view of Spain contrasts with the country's macroeconomic performance of recent years, which has seen its GDP grow steadily since emerging from the eurozone crisis over half a decade ago.

But Mr Alston and others say that austerity measures aimed at balancing Spain's finances at the height of the economic crisis have left a devastating and lasting legacy.

"We've had a period in Spain during which the most vulnerable population has not been the priority," says Carolina Fernández, of the Fundación Secretariado Gitano (FSG), a non-profit organisation that promotes the rights of the Roma (Gypsy) community.

"If you don't invest in those who are living below the median, then they are going to drop below it even further."

The Roma, who number up to a million in Spain, were one of several groups that the UN rapporteur identified as being particularly marginalised.

According to FSG figures, 92% of the community are at risk of extreme poverty, while 52% are unemployed, compared with an unemployment rate of 14% nationwide.

In Polígono Sur, people of Roma ethnicity make up nearly a third of the population.

Jaime Bretón, the local commissioner responsible for the district, insists that the national, regional and municipal authorities are trying to turn things around for them and all the residents of Polígono Sur.

"The important thing is for the administration not to throw in the towel," he says. The authorities, he argues, must try to persuade locals that education and professional training provide better long-term prospects than the "shortcut" offered by crime.

One in four Spaniards is at risk of poverty or social exclusion

"It's not a question of solidarity or social support, it's about citizens' rights," he says. "We have to give back to the people who live here their rights as citizens."

Vulnerable immigrants

Last year, Mr Alston was highly critical of the UK's failure to tackle poverty.

The kids trying to stop "holiday poverty" in the UK

In Spain, other communities he identified as being particularly vulnerable included children, the disabled, those in rural areas and immigrants. The vast majority of the country's estimated 600,000 domestic workers are immigrant women.

Carolina García from El Salvador is a representative of the Association for Domestic Workers and Carers in Zaragoza, in north-eastern Spain. She says that the unregulated nature of the sector makes it difficult for workers to have a contract and a job for three years - both required in order to gain residency papers.

The lack of regulation also means wages can be woefully low.

"Often [employers] are not even paying the minimum wage, which is €950 [£830; $1,060] ] per month as of 2020," Carolina says. "There are people earning €500, €600 or €700."

Spain is expected to keep outperforming many of its EU neighbours this year, with its central bank forecasting economic growth of 1.7% - coronavirus permitting.

But the country's new left-wing government, made up of the Socialist Party of Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez and the leftist Podemos, is hoping that in meeting such targets it does not leave behind the many Spaniards at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder.

Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias told parliament the government was committed to ensuring that in the future Spain did not "have to feel the shame of having an international rapporteur from the UN come to our country and denounce a situation of poverty and inequality that is unacceptable in the eurozone's fourth economy".

- Published20 November 2016