Coronavirus: Why Dutch lockdown may be a high-risk strategy

- Published

Trams are all but empty, but under the Dutch lockdown not everything is shut

The Netherlands has tried to adopt an "intelligent lockdown", but the infection is spreading rapidly and it has one of the world's highest mortality rates from the pandemic.

The Dutch have also been accused of failing to show solidarity with countries in southern Europe hit hardest by coronavirus.

So what are the Dutch trying to achieve and how has stricken Italy reacted?

What is an 'intelligent lockdown'?

The Dutch are among the few who began by openly embracing the contentious idea of group or herd immunity. It's an approach characterised by one Dutch global health expert as cold and calculated.

Having shunned the stricter measures of neighbouring states the government has pursued an "intelligent" or "targeted" lockdown. It wants to cushion the social, economic and psychological costs of social isolation and make the eventual return to normality more manageable.

Bakeries may still be operating but the beaches are all but deserted

My local florist, ironmonger, delicatessen, bakery and toy store are still serving customers. Posters on the door and sticky tape on the floor encourage people to give each other space. Staff at the tills wear surgical gloves.

Only those businesses that require touching, like hairdressers, beauticians and red light brothels, have been forced to cease trading.

Schools, nurseries and universities are closed until at least 28 April.

Children's daycare centres are largely closed except for workers in key professions

Bars, restaurants and cannabis cafes are shut, although they seem to be doing a roaring trade in takeaways.

"We think we're cool-headed," explained Dr Louise van Schaik of the Clingendael Institute of International Relations. "We don't want to overreact, to lock up everybody in their houses. And it's easier to keep the generations apart here, because grandpa and grandma don't live at home with their children."

Dutch PM tells nation not to shake hands – then does

People have been advised to stay at home, but you can go out if you are unable to work from home, or have to grab groceries or fresh air, as long as you maintain 1.5m (5ft) social distance.

It helps that the Dutch appear to be broadly compliant. One survey suggested 99% of people kept their distance and 93% stayed at home as much as possible.

Prime Minister Mark Rutte described the Netherlands as a "grown-up country". "What I hear around me, is that people are glad that they are treated as adults, not as children," he said on Friday.

Sometimes this lockdown feels invisible. Cities may be quieter, but children still clamber on climbing frames and teenagers cycle side-by-side.

How Dutch went beyond UK on herd immunity

When the UK's chief scientific adviser revealed a plan to develop a broad immunity across the population, within days researchers revealed it could claim a quarter of a million lives, and the UK changed course.

Allowing a deadly virus to spread through society to create a level of immunity implicitly means accepting people will die.

Dutch health minister Bruno Bruins collapsed in parliament because he was so exhausted by dealing with the crisis

It was initially embraced by the Dutch government too, but then rapidly repackaged as a useful by-product rather than the main goal.

In a televised speech to the nation on 16 March, Mr Rutte outlined his approach, external.

"We can delay the spread of the virus and at the same time build up population immunity in a controlled manner," he said.

The bigger the group that acquires immunity, the smaller the chance that the virus can make the leap to vulnerable older people or people with underlying health issues

"We have to realise that it can take months or even longer to build up group immunity and during that time we need to shield people at greater risk as much as possible."

Prof Claes de Vreese of the University of Amsterdam believes the UK government did not have measures in place for such a policy. "It left people dangling and feeling like they were part of a bizarre social experiment," he says.

Can it work?

Dutch public health agency RIVM has launched a study to see how far antibodies created when people are exposed remain effective in preventing re-infection.

"It's kind of like creating your own internal vaccine, by being exposed to it and then letting your body generate those antibodies naturally, to turn into a vaccination which doesn't yet exist," Prof Aura Timen from the RIVM told the BBC.

She stressed they were still doing all they could to slow the pace of transmission of Covid-19 to "flatten that curve".

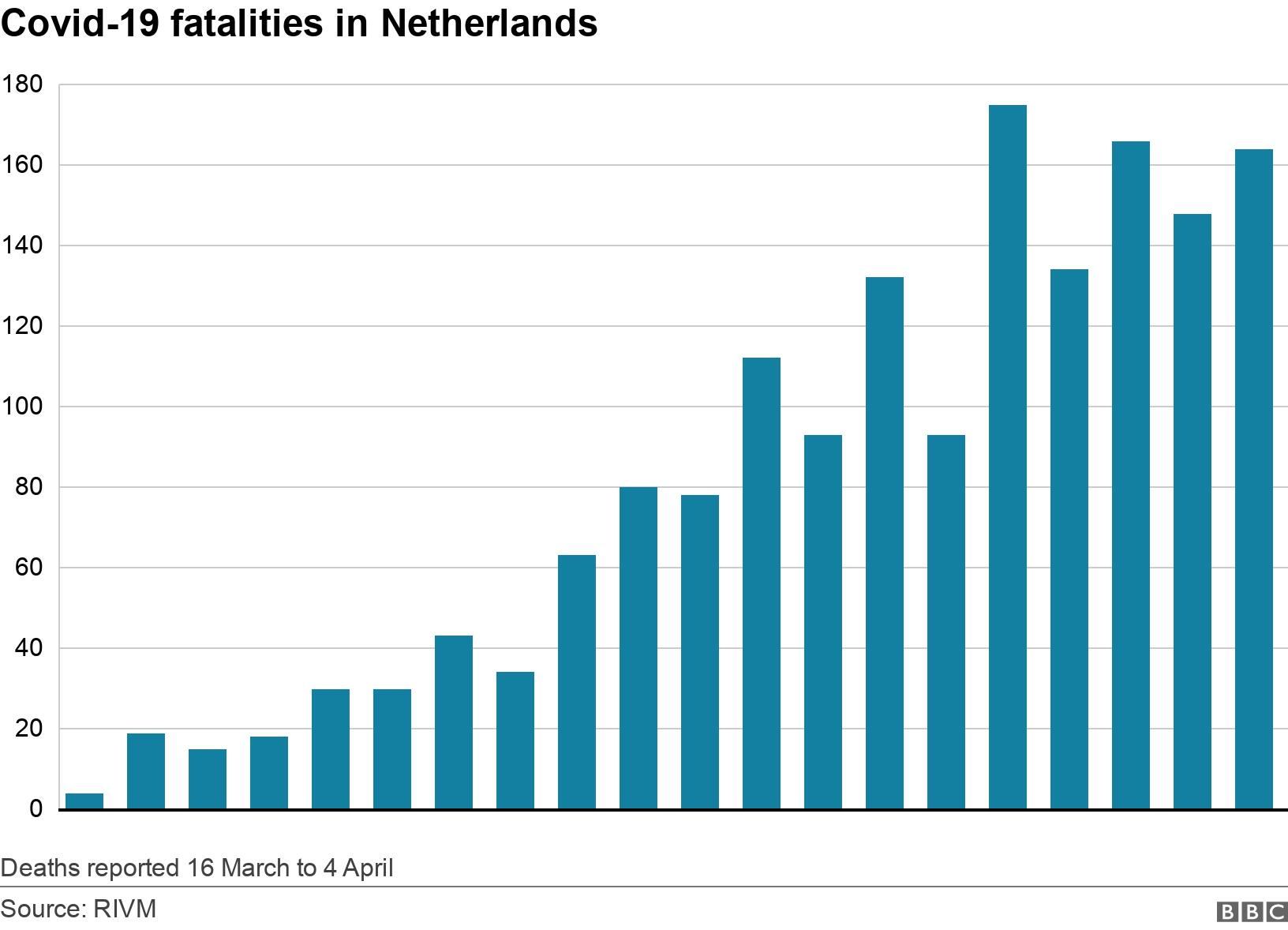

The problem is that the number of deaths in the Netherlands seems relatively high for a population of 17.2 million. But in neighbouring Belgium, which has a smaller population and a stricter lockdown, numbers have also been high.

Prof Timen believes the high figure in the Netherlands is down to effective reporting: "We have a good reporting system for people who have become infected, who have been hospitalised, but also for death."

Reality sets in as deaths rise

The Netherlands is now scrambling to increase its hospital capacity, with the peak of the crisis anticipated in two weeks and deaths as high as 175 in one 24-hour period. Some 1,650 people have died since the crisis began and over 6,600 have been admitted to hospital.

Some patients have been transferred to Germany to free up beds and the Ahoy Rotterdam concert hall, which was supposed to host Eurovision 2020, is to become an emergency facility.

There are plans to quadruple the number of tests and healthcare workers not directly involved in treating coronavirus patients will also be screened.

But there have been setbacks too.

When a million masks shipped in from China were deemed faulty, the government had to order an urgent recall.

Artist Laurie Schram at Space Fantastic is running a team of volunteers sewing masks

There is a shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), so students in Delft are working on transforming swimming snorkels into surgical masks and local artist Space Fantastic is collecting fabric donations and running a legion of volunteers frantically sewing masks for those on the front line.

How the Dutch enraged the Italians

The Dutch are largely pro-European, so when a letter by prominent Italians to a German paper condemned them for a "lack of ethics and solidarity in every respect", the words stung.

The Italian letter published in a German paper condemned a lack of Dutch solidarity and ethics

The Netherlands and Germany led opposition to easing the debt burden on southern states through the issuing of "coronabonds".

Both countries pay more into the EU than they get out, but this "scroogy", arrogant Dutch approach was destined to backfire, says global health lecturer Remco van de Pas of Maastricht University.

What's more, it is seen as self-defeating.

"If the whole south collapses, the rich north ceases to exist," as Dutch National Bank ex-president Nout Wellink put it bluntly.

The Dutch rely on other EU countries buying their exports, says Prof Claes de Vreese.

"We have a shared interest bouncing out of it in economic terms in a way that keeps the union and the euro in a strong place."

Then came an admission from the Dutch finance minister. Yes, the Netherlands' initial response lacked empathy.

We were not empathetic enough, to the point that it has raised resistance. We did not succeed in conveying what it is we want to do

Prime Minister Rutte proposed an EU emergency fund to cover the immediate medical costs of the crisis, with contributions from the member states. "It would not serve as a loan or guarantee, but as a gift to those in need."

Their hand was forced.

"The Dutch have benefited tremendously from the European Union, its open labour, market and mobility," Dr Van de Pas told me.

But the idea of an intelligent lockdown, driven by evidence and numbers, is very different from the stricter approach in neighbouring Belgium, where fatalities have also been high.

For Dr Van de Pas it's a cold and calculated Dutch approach, that can perhaps only work in an individualistic society used to a non-interventionist medical culture, from cradle to grave.

While herd immunity, modified as it is, may eventually dampen the effects of the epidemic, it has to be accepted by a substantial part of the population.

The worry is that the Dutch approach may be based more on aspiration than actual intelligence, and that the Netherlands' "intelligent lockdown" does not make the country immune.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

- Published10 March 2020