How Typhoid Mary left a trail of scandal and death

- Published

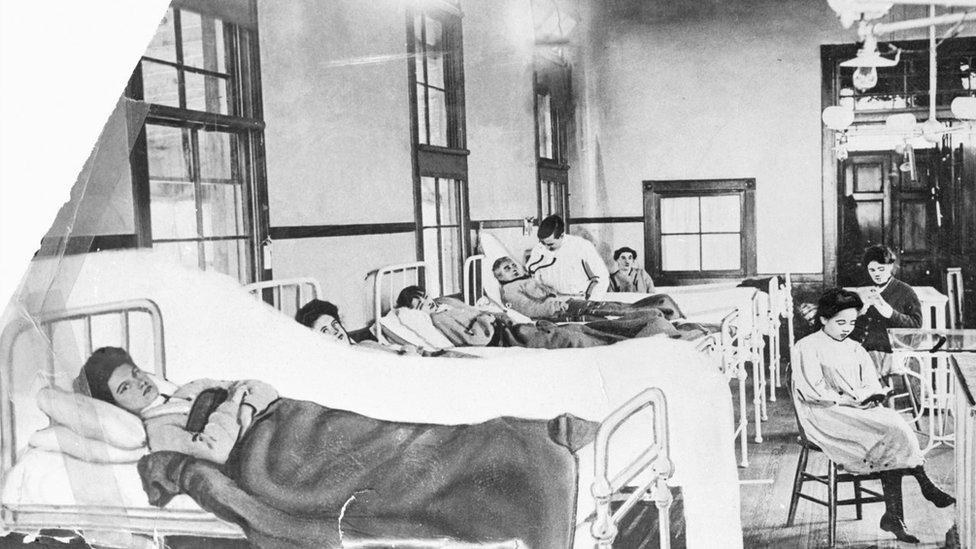

Mary Mallon, here in the foreground, never contracted typhoid herself but was responsible for spreading the disease

No-one ever thought we'd see a time when every news bulletin and website in the world would be filled with stories of a global health crisis and the scientific race to beat it.

But this is not the first time that epidemiology has captured the public imagination.

There was the "Spanish" flu epidemic of 1918-1920 that infected a quarter of the world's population and killed anywhere between 17 and 50 million people.

But even before that there was the extraordinary story of Typhoid Mary, a young Irish immigrant working as a cook in New York at the beginning of the 20th Century who left in her wake a trail of death, scandal and controversy.

Irish cook with a signature dish

At some points in her story Mary appears to be a victim and at others a villain, but she certainly made epidemiology the talk of New York and the wider world in the years just before World War One.

Mary Mallon was born in Cookstown, County Tyrone, in 1869 but left Ireland as a teenager to seek a new life in the New World.

By 1900 Mary was a cook working in the houses of wealthy families in and around New York City. Her signature dish was said to be peach ice cream.

Somewhere between one and two million Americans worked in domestic service back then and to be a cook was to be Queen of the Castle.

You managed the kitchen staff, bought in supplies and to prove your status you were to your employers Miss Mallon, and not merely Mallon.

Killer disease stalked New York

Mary Mallon worked in the ritzier parts of Manhattan but things were not going as well as they seemed.

Between 1900 and 1907 she cooked in the homes of seven families - the last one on Park Avenue - and in every one of them people fell sick or died. Each time she slipped away and found work elsewhere.

Her wealthy employers in places like Oyster Bay and Fifth Avenue were shocked.

Typhoid was a killer but it belonged to another world. The disease thrived in the overcrowded, insanitary conditions of New York's slums, such as Five Points, Prospect Hill and Hell's Kitchen.

The family of one of the victims hired a researcher called George Soper and the diligent Mr Soper proved to be Mary's nemesis - even though when he first tracked her down she chased him out of her kitchen with a carving fork.

And that's part of the problem with Mary.

This illustration from around 1909 shows Typhoid Mary breaking skulls into a skillet

It's possible to sympathise with her refusal to believe that she could be transmitting a disease from which she never suffered herself. But Mr Soper had correctly identified her as an asymptomatic carrier of Typhoid fever.

She would never get the disease herself but would never stop giving it to other people.

Not surprisingly, Mary Mallon found this impossible to understand. But the New York authorities were desperate and in 1907 Mary was exiled to the isolation facility on North Brother Island in the river outside New York.

What is typhoid fever?

Typhoid fever is caused by highly contagious Salmonella Typhi bacteria and spread through contaminated food and water

It is most common in countries with poor sanitation and a lack of clean water

An estimated 11-20 million people get sick each year, and between 128,000 and 161,000 people die

There are two vaccines to prevent typhoid; it can be treated with antibiotics although resistance to antibiotics is making treatment harder

Bacteria can be shed by chronic carriers who show no symptoms, in some cases even for decades; Mary Mallon was the most famous, external.

North Brother Island is an uninhabited bird sanctuary these days - it sits in the East River near the Bronx.

In the late 19th Century it was built to house victims of smallpox and was eventually given the task of keeping in isolation anyone suffering from a quarantinable disease.

The treatment may seem brutal by modern standards but before the invention of antibiotics there was no other way of containing such diseases. The Greater New York Charter gave state health authorities the power to order the sick into isolation.

Mary Mallon was held, essentially, in solitary confinement. She planned legal action and told her lawyer that it was unjust to treat her as an outcast when she had done nothing wrong.

Mary Mallon is pictured here, fourth from R, in quarantine

"It seems incredible," she said, "that in a Christian community a defenceless woman can be treated in this manner."

Mary won her freedom in return for a promise that she wouldn't work as a cook again.

How newspaper baron Hearst took up Typhoid Mary's cause

Her case had been taken up by newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, who was once said to have demanded that every story in his papers should cause the reader to rise from his seat with a cry of "Good God!".

Hearst was a publisher of extraordinary influence and it was in his newspaper The New York American that her story was first told in full on 20 June 1909.

Hearst's support was something of a double-edged sword. The publicity he generated gave Mary the money to hire a lawyer.

Hearst may even have paid the legal bills, as he was thought to have done before in cases that provided good copy. On the other hand, his reporters appeared to have coined the nickname Typhoid Mary which stuck for the rest of her life.

How life after freedom turned sour

She tried working in the lowlier job of laundry maid but eventually returned to cooking under a string of assumed names. She even, unforgivably, took a job in the kitchens of a hospital.

The now familiar trail of death and sickness pursued her. It's impossible to know how many deaths she was responsible for. There were certainly at least three but more lurid accounts suggest there might be as many as 50.

When authorities tracked her down again in 1915 there was no newspaper campaign and no sympathy.

Mary was sent back into isolation and lived in confinement for 23 years until her death in 1938. Her legacy perhaps is a lesson about following medical advice even when you don't really understand it.

But why was Mary Mallon's signature dish of peach ice cream so important to her story?

The typhoid bacterium can live in cold food but is destroyed by cooking. If she had taken a special pride in her apple pie perhaps we would never have heard of Typhoid Mary.

You can hear the Typhoid Mary story in Radio 4's From Our Own Correspondent here.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

HOPE AND LOSS: Your coronavirus stories

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash