Coronavirus: Why fractious EU still believes together is better

- Published

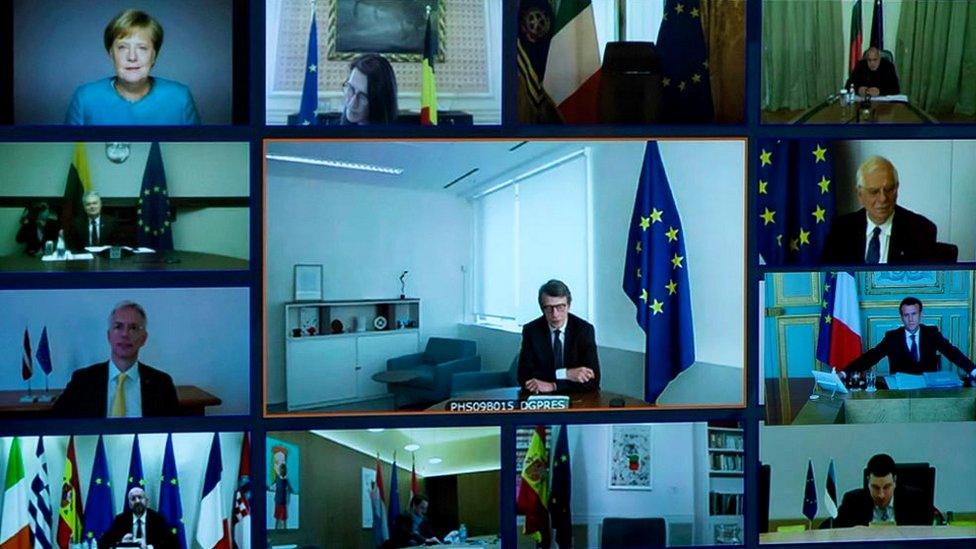

EU leaders will meet by video for their summit on Thursday

"EU in disarray!" scream headlines since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. Brussels is depicted as "weak"; EU member states as "feuding".

You find endless analyses online focusing on the "lack of solidarity" shown by the rich EU North: Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Finland - the "frugals" as they've been dubbed - towards the suffering South - i.e. Italy and Spain.

In the UK, the EU's handling of coronavirus feeds into what's left of the Brexit debate.

The UK has already left the EU, of course, but Remainer/Leaver resentments linger. And the question of how close the UK remains to Brussels in the future is not yet enshrined in law.

Does EU behaviour during the pandemic mean we were right to leave or wrong? Twitter is not exactly short of thoughts on that subject.

But are media depictions of the EU and its members so far during this crisis entirely accurate?

"Are they ever?" huffed a key Brussels figure when I asked him. "We've had ugly moments but by now the achievements are stacking up. The massive ECB (European Central Bank) stimulus package was just the beginning. Thursday is a big day."

Agreeing on an emergency fund and common measures

EU leaders meet by video-conference for a summit on Thursday afternoon.

They're expected to sign off on a new €540bn (£470bn; $575bn) emergency fund to protect European workers, businesses and countries worst affected by the coronavirus outbreak.

The Italian prime minister needs to show he is being listened to in Brussels

The fund was difficult to agree between member states but they got there in the end. After considerable push and pull, plus a dramatic intervention by French President Emmanuel Macron, who threatened the end of the EU if agreement wasn't found.

"So much for us failing to show solidarity with Italy," snorted a Dutch colleague to me. "It's a generous package."

Angela Merkel's preferred wording was that solidarity had been shown towards Italy and the South. It would continue to be shown in the future, she said.

Brussels boasts that, in addition to the fund, EU members have been sharing protective medical equipment and specialist medical teams with one another.

The German military has airlifted coronavirus patients from the heart of Italy's pandemic for treatment in Germany

In some cases, they've also been treating each other's patients. According to German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, the cost of providing treatment to patients coming from abroad has cost the German taxpayer €20m so far.

On Thursday, EU leaders are also expected to approve common measures for gradually lifting coronavirus restrictions.

This does not mean coordinating an EU-wide End of Lockdown. Each country has its own health service, with different infection patterns, different lockdown measures in place.

Would the spread of coronavirus have been more easily contained if all EU countries and their neighbours had taken early and uniform precautions?

Indubitably, say medical experts. But that kind of agreed action hasn't been possible amongst the states of the United States of America. It was never going to happen between 27 independent EU countries, with their varying forms of government (federal, regional etc).

Can EU agree roadmap from here?

Brussels admits every member state will now "tailor-make" their exit strategy from lockdown but it wants them to at least inform one other in advance, to avoid complications for people working across national borders.

The Commission has also asked that no EU country lift its Covid-19 restrictions unless:

The number of deaths/infections in that country has been reducing and stable for a sustained period of time

The national health service could cope with a surge of new infections if necessary

The EU country in question has enough testing capacity to identify and quarantine new infections plus people they have recently been in contact with, in order to keep those who have not yet had the virus safe.

EU leaders are broadly in agreement with all of this, but smiles could turn to gritted teeth when they then turn their attention to the future.

One of the summit priorities on Thursday is to discuss a Recovery Plan for Europe: aimed at getting European economies back on their feet after the health crisis is over.

The kind of figure that's being discussed is around €1-1.5 trillion.

Italy’s lockdown puts restaurants out of business

The main recipients would be European countries with the weakest economies.

France's President Macron wants the programme to be time-limited to about five years. He hopes it will be "oven-ready", signed off by parliaments across the EU, by the end of the year.

But where the plan is still vague and contested is what form funds should take: loans or grants?

Should the money be raised as part of the next EU budget (which needs to be decided by the December) or alongside?

As always, national politics is key.

The German chancellor will leave office in 2021

Apart from Germany's Angela Merkel - who will not want the EU to fall apart in her last term in office - the big players in this debate are all vying to be re-elected. They're keen to prove their credentials to a domestic audience.

Solidarity or self-interest?

With an eye on Eurosceptic politicians at home, the Dutch prime minister wants to be seen to be protecting Dutch taxpayers' money on the European stage.

Italy's prime minister also needs to show he's sticking up for his country in Brussels. Italy was one of the EU's most Eurosceptic nations even before the coronavirus crisis.

And France? Emmanuel Macron is always looking over his shoulder at arch-Eurosceptic and political rival Marine Le Pen.

He's trying to weave a delicate dance between giving the French the impression that he's leading the post-virus recovery charge in Europe, while trying to get extra cash for the countries of the Mediterranean (including France), yet trying hard not to alienate Berlin, which he hopes will foot the largest chunk of the bill.

Quite the juggling act.

The French (and Italian and Spanish) argument is now refocused, not on solidarity but self-interest.

Their message to the frugal North: we all benefit from the single market. It's worth spending a bit more in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis to rebalance inequalities between members to make the market more competitive and lucrative in the long term.

Otherwise you risk the market faltering altogether.

President Macron wants the EU's Recovery Plan signed off this year and limited to five years

This message dovetails with the ambitions of the still relatively new presidents of the European Commission and the European Council.

They believe coronavirus has made the failings in the way China and the US function glaringly obvious.

They hope that will make way for a reborn and rebooted EU to play a bigger role on the world stage - economically, in terms of a Green revolution, and digitally - after the crisis is over.

This, anyway, is the cherished dream in Brussels right now.

And as part of such a long wishlist, the details of the post-health crisis Recovery Fund are unlikely to be agreed anytime soon.

Following their Thursday summit, EU leaders will ask the European Commission to come up with concrete proposals but insiders say the painful process of compromise over the fund and the new EU budget is only likely to happen when leaders sit together in person. And who knows when that will next be?

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, there were calls all over the EU to leave the bloc. This time it's different. Eurosceptic politicians haven't gone away. Plenty of voters are still critical of Brussels. But the call to leave the EU altogether has broadly fallen silent.

EU relations are messy and further complicated by national politics but most EU leaders think the Covid-19 programmes they've got up and running together, are better than those they'd have achieved alone.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

HOPE AND LOSS: Your coronavirus stories

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

- Published21 June 2021

- Published15 April 2020

- Published20 April 2020