Coronavirus: Russian republic Dagestan enduring a 'catastrophe'

- Published

When oxygen ran out, local residents went on long trips to help replenish canisters in their hospital

Dr Ibragim Yevtemirov still coughs every so often as he talks. A paediatric trauma surgeon in Dagestan, in the Caucasus region of southern Russia, his ward had been full of Covid-19 cases for a couple of weeks when he got infected himself.

He says seven colleagues in his town have now died, including nurses, orderlies and laboratory staff, according to a count kept by local medics themselves.

"All three doctors on my team got sick. We were replaced by dentists until we recovered," Dr Yevtemirov told the BBC by phone from Khasavyurt, where he's now back at work in the central hospital.

"At the peak, there were 10, 11 patients dying a day here," he says.

How Dagestan's disaster was revealed

The doctor's account of dire shortages and deadly chaos is just one, stark snapshot of a Covid-19 crisis in Dagestan so serious that the republic's chief mufti this week described it to President Vladimir Putin as a "catastrophe".

Local Dagestanis put up checkpoints in an attempt to stop the spread

As the holy month of Ramadan ends this weekend, Akhmad Afandi has been urging people in the mainly Muslim republic not to gather to celebrate Eid with friends and extended family - as it may cause a further dangerous spike in cases.

But it was a startling interview with the local health minister that first exposed Dagestan's struggle with this epidemic.

The minister told a blogger that 40 medics had died in the republic: more than the total, official number of Covid-19 fatalities.

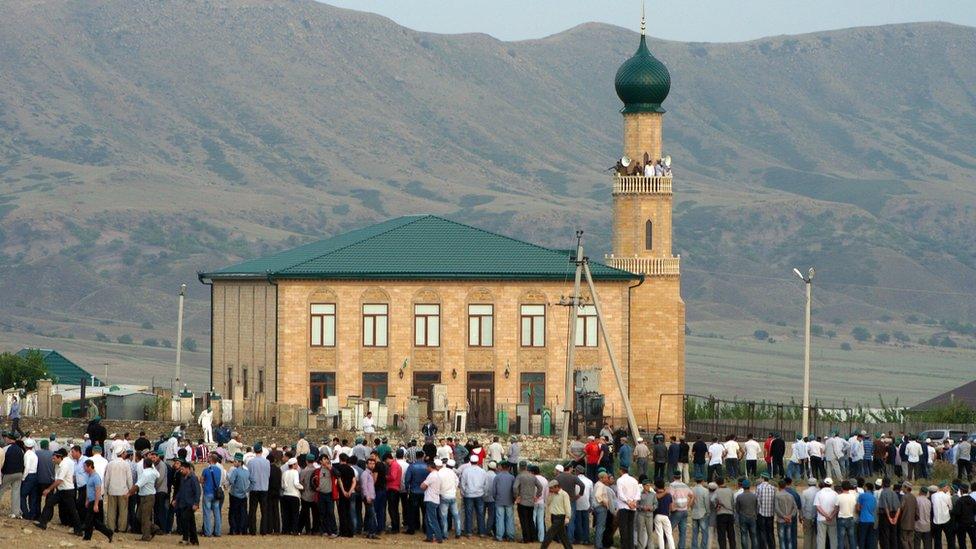

Much of Russia's republic of Dagestan is mountainous

"At the start, the kit we were given was very primitive," Dr Yevtemirov explains, from his personal experience.

"It's not that we weren't worried, but when this epidemic hit there was no alternative. It's like we had to rush straight into battle," he says.

Why Dagestan's true toll is unclear

The health minister's interview also revealed that hundreds of people had died of "community-acquired pneumonia" in Dagestan - with all the same symptoms as Covid-19 - casting further doubt on Russia's low official mortality rate from coronavirus.

"Our hospital is full of Covid cases, but only a tiny handful of patients have a confirmed diagnosis," Dr Yevtemirov clarifies, saying that most of the swabs the hospital sends off for analysis are recorded as pneumonia.

Like other countries, Russia only adds cases with a positive test result to its daily death toll.

Russia's emergencies ministry this week sent disinfection equipment to Dagestan as the scale of the crisis emerged

"Perhaps there's a problem here with the tests, or something. Some think there's been an order from above not to diagnose Covid, but I can only guess," the doctor says.

Was Moscow's messaging to blame?

Data on how deeply the infection has penetrated Dagestan is also hard to be sure of.

Until recently, the republic was conducting fewer than 1,000 tests a day, lacking both the equipment and laboratory capacity for more.

"The hospitals only dealt with the seriously sick, no-one was testing anyone else," explains Ziyautdin Uvaisov of advocacy group Patient Monitor.

Like many, Mr Uvaisov believes the spread of the virus was helped by mixed messaging from Moscow, coupled with deep-rooted mistrust of officials.

"People on TV kept saying it's no worse than normal flu," he points out, adding that official orders to stay at home were then widely ignored.

How Dagestanis protected themselves

Dagestan was always going to be susceptible to coronavirus. Many local men are long-distance truck drivers, criss-crossing Russia to travel to Iran and beyond.

There are also close links with Moscow and when the Russian capital declared a lockdown at the end of March many Dagestanis flowed back to their villages, unchecked.

The local hospital in Gurbuki opened only in December and local children were seen dancing in celebration

The village of Gurbuki was better served than others to cope.

A brand new hospital was opened in December to great fanfare. But when in April suspected Covid-19 cases began filling up beds, a staggering 50% of medical personnel fell ill.

Locals didn't wait for government help to take action.

Volunteers, mainly young men, began helping out on the wards; others stepped in to set up checkpoints at the village entrance to try to control the infection's spread.

And when the hospital began running dangerously low on oxygen, it was volunteers who travelled the 120km (75-mile) round trip to the Dagestani capital, Makhachkala, to refill all the gas canisters they'd begged and borrowed off villagers.

"At the peak they were travelling three times a day, to bring oxygen for the wards," village head Magomedkhabib Mamatgereev told the BBC.

Local areas have been disinfected in an attempt to stop the virus being transmitted

"The canisters are really heavy and it's a lot of work, but they did it all for free. They're our heroes!"

Despite their efforts, at least 10 people have died in the local hospital and some 30 in the village itself.

"Of course we expected more from the Dagestani government, but I don't want to criticise anyone," the village head reflects. "At the start we had nothing: no PPE, no medicine. We hoped the virus wouldn't affect our village," he admits.

"But we coped. And now things are getting better."

More stories from Sarah:

The sudden focus on Dagestan has brought belated promises of urgent, extra resources from Moscow - though Vladimir Putin appeared to blame local people for the "complications", suggesting too many had tried to treat themselves at home.

An inspection team confirmed the republic's poor testing capacity for Covid-19, a lack of PPE, medicine - and even medics.

But there are signs that the immediate crisis is beginning to ebb.

"Fewer people are being brought in and fewer are dying," Dr Yevtemirov confirmed, adding that staff at his hospital in Khasavyurt do now have protective clothing.

But he's concerned that Eid celebrations could shake the new, tentative stabilisation.

People have been crowding local markets, he says, despite imams sending WhatsApp warnings not to lay on food to share with neighbours.

"I think they'll gather together less, but it won't stop totally," the doctor worries, ahead of another shift on the Covid ward. "People are a little bit undisciplined."

More BBC stories from Russia's southern republics

Russia's IS families: "Why are the children being punished?"

- Attribution

- Published19 May 2020

- Published21 March 2019

- Published19 February 2018

- Published30 October 2023

- Published18 August 2016

- Published2 July 2016

- Published30 June 2015

- Published24 November 2011