Surfing tragedy that stunned a Dutch beach community

- Published

Rescuers were confronted with abnormal sea conditions that claimed the lives of the five young men

It was supposed to be a celebratory bodysurf, a chance to train together again the night before the official start of the summer season. But a month ago in The Hague, five gregarious, athletic young surfers lost their lives in freak sea conditions, on their first return to the water since coronavirus restrictions had forced them apart.

Joost, Sander, Pim, Max and Mathijs fell victim to a thick wall of metres-high foam and rough seas. The bodies of four were recovered within 24 hours.

Then last week I watched as firefighters extended a ladder to recover 23-year-old Mathijs's body from boulders beneath the lighthouse at the end of Scheveningen pier.

Gazing at the waves crashing on to the rocks, I shared the sense of disbelief that still perforates this coastal community.

Why did they die?

The five were all experienced surfers and coaches. Their surf school said they had classes scheduled for the whole week , externaland a final blog posted a few hours before their deaths showed they were itching to hit the waves.

The group had discussed the foam and considered going in at another point, another surfer who survived told friends.

But both wind and current had changed rapidly. An unusually strong north-northeasterly and a suffocating avalanche of algae foam proved a treacherous combination.

Suddenly, these experienced, responsible young surfers trained to save others were unable to save themselves.

"You just hope the moment of frantic panic was over fast," Joost's childhood friend Timo van de Ven told me. He still struggles to accept they won't be coming back.

Dutch sea rescue service KNRM said the strong wind and current made their operation "a tricky job".

How community was caught up in grief

Scheveningen is known as the surf capital of the Netherlands. It's a popular destination that relies on storms near the coast to generate decent, rideable waves.

I live a 10-minute cycle away from the spot where the surfers died. Year-round we watch surfers dashing into the icy North Sea, propelled by the thrill of catching a wave. They bob and dip on the horizon like seals in their sleek black-and-blue wetsuits.

"The grief in the Scheveningen community is unimaginable," said Johan Remkes, acting mayor of The Hague. "People here understand better than anyone else that the sea gives and the sea takes away, but the way so many young lives are now being broken down and so many families and groups of friends have been affected is uniquely cruel."

What's striking about the deaths of these experienced surfers is that they were doing something so normal, in a stretch of sea they knew like the back of their hands.

Friends congregated on the stone steps leading down to the beach a week after their deaths. Cafes closed by the coronavirus crisis played tunes to crowds of students. Surfers tried to console one other, wrapped up in hoodies and each others' embrace.

Police on bikes circled respectfully from a distance, allowing people to be together when they were meant to stand apart, leaving friends to grieve and not worry about infection.

"It's helped to feel part of a wider grief, going there and being among people who understand," a friend of the group told me. The five were not just socially active, they were known across the community, among all ages.

Tributes alongside a sea of flowers outside The Shore surf school offered a snapshot of the five who touched so many young lives.

Five beer bottles stood alongside framed photos and notes like "RIP, wild hearts"; a poem circulated on social media with the opening line, "The waves are silent witnesses on an even quieter beach."

It felt unusually still on the beach for days afterwards, as if the shock had reverberated on the sand and disrupted the breezy atmosphere.

Who were the five?

Joost Bakker, 30

Joost Bakker loved the sea and helped autistic children

Surf instructor Joost was described by friends as a stereotypical surfer. As a lifeguard, he was well aware of the hazards. He moved to The Hague to be close to the sea, converting a van to spend more time by the shore.

Bakker coached autistic children and once organised a sponsored cycle ride from Norway to Gibraltar to raise money for a charity that supports people with cancer.

His friend, Timo van de Ven, knew him since they were 12. "After the intense emotion of the first few weeks, the finality is the hardest part. He died doing something he loved, the last photo shows him smiling from ear to ear, getting ready in his wetsuit. That's some consolation."

Sander Dikken, 38

He was enthusiastic and competitive and loved to swim between the piers at Scheveningen. He too was a lifeguard and surf instructor, and studied kinesiology (the mechanics of body movement) at the University of Groningen.

That enhanced his teaching at Health by the Sea (Gezond aan Zee), where he worked alongside Joost.

Pim Wuite, 24

He was one of the younger surf coaches at Gezond aan Zee. A condolence note shared by his hockey club speaks of a smiley, sweet young man with boundless energy, leadership skills and commitment to youth training.

Cricket-loving friends laid flowers on the beach and remembered how his parents would often provide lunch for the team. He was meant to visit Bali this year, until flights were grounded by the coronavirus crisis.

Max Verheijen, 22

The youngest of the five, he was close to completing a degree in mechanical engineering in Delft, near The Hague. A snowboarder who switched to the sea, Max was described by his family as smart, friendly and always ready to have fun.

His body was carried in a casket through the central Dutch village of Muiderberg where he grew up, followed by pallbearers carrying his beloved surfboard decorated with a bouquet of white roses. Flags flew at half-mast and some draped wetsuits over the flagpoles in memory of the boy who lived for the waves.

Mathijs van Dulst, 23

He was a children's hockey coach and referee, and had been looking for someone to sublet his room in the house he shared with 14 others.

Photos of his room show a cluster of snow and surf boards propped up in a corner of his bedroom.

A tribute on his hockey club page says he trained the younger kids and showed the older ones how to party.

"We carry them forever in our hearts," reads a tribute from their colleagues at their surf club, "Our friends are gone. You live on in our hearts."

Five flowers were planted on the beach in memory of the men who died

What caused the freak foam?

The nature of their deaths has intensified the anguish and confusion that cuts beyond the surfing community.

What is hard to understand is how they were caught up in freak conditions when a short distance away other people continued riding the waves into the sunset.

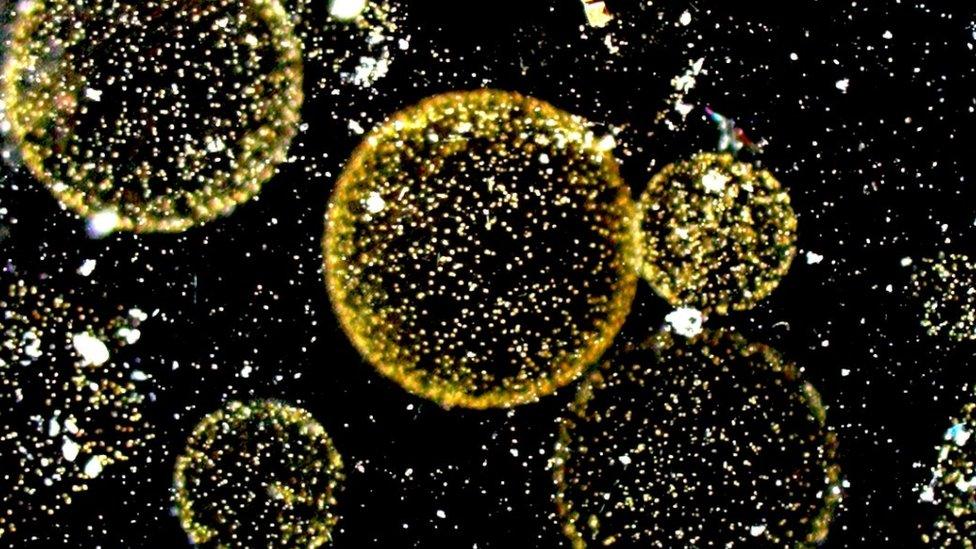

The sea foam that led to their deaths comes from a type of algae called phaeocystis globosa. Scientists from the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (Nioz) have worked out what they think must have happened.

Colonies of algae are held together by a mucous-like matrix that protects the cells and allows them to rapidly increase in size.

The algae need sunlight and nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphate, and a sunny start to May helped the cells grow rapidly. The sea foam off Scheveningen was found to be four times the average peak seen in the past 10 years.

However, cloudy weather the day before the tragedy triggered the disintegration of the algae colony into an "unparalleled" quantity of individual cells.

Viral infections caused the cells to burst open and a Force-7 wind and strong seas whipped them up into a large amount of foam.

The north-northeasterly wind drove the foam against a harbour head before the currents changed and the foam moved towards the beach.

The scientists believe lifeguards and water sports enthusiasts need to be alerted to the potential risks of high levels of sea foam. They say it will take time to establish a proper warning system for the future, to prevent further accidents.

Meanwhile, five white fish have been painted on the rocks at Scheveningen near the spot where Joost, Sander, Pim, Max and Mathijs were last seen alive.

When the other tributes have gone, these will be permanent reminders of the memories they left behind.

More stories that may interest you:

Sea foam floods Spanish streets of Tossa De Mar

All pictures are subject to copyright.

- Published22 January 2020